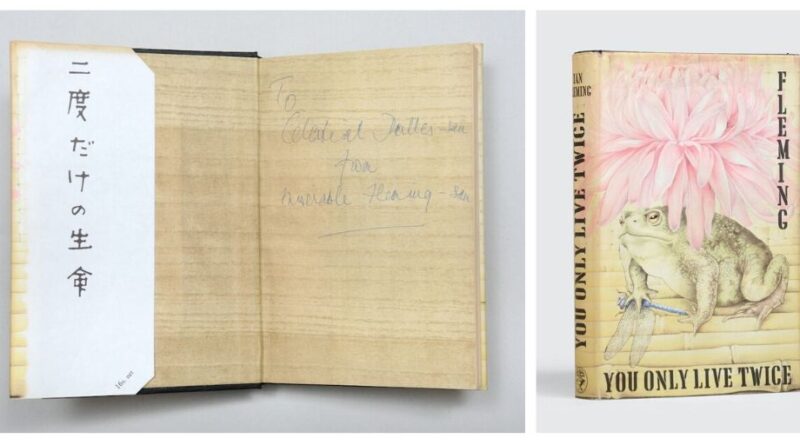

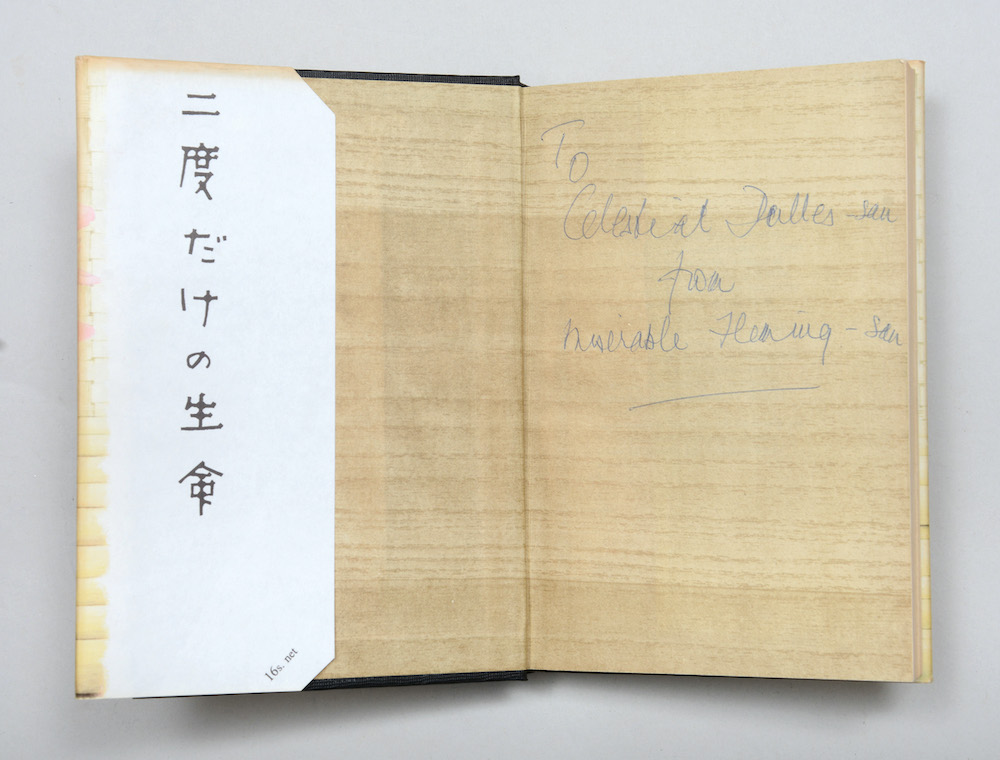

Rare inscribed copy of You Only Live Twice

A fine presentation copy of You Only Live Twice, inscribed by the author Ian Fleming to former CIA Director Allen Dulles is being offered for sale by London-based rare book dealer Peter Harrington for £27,500.

The first edition presentation copy features the inscription: “To Celestial Dulles-San from Miserable Fleming-San”.

The humorous mock-Japanese inscription reflects the subject matter of the book, yet also the familiarity between the two men, both having held senior positions in their nation’s respective intelligence agencies. Dulles, furthermore, is praised by name in the novel when M complains the CIA have stopped revealing information to MI6: “They regard that as their private preserve. When Allen Dulles was in charge, we used at least to get digests of any stuff that concerned us, but this new man McCone has cracked down on all that” (page 41).

The humorous mock-Japanese inscription reflects the subject matter of the book, yet also the familiarity between the two men, both having held senior positions in their nation’s respective intelligence agencies. Dulles, furthermore, is praised by name in the novel when M complains the CIA have stopped revealing information to MI6: “They regard that as their private preserve. When Allen Dulles was in charge, we used at least to get digests of any stuff that concerned us, but this new man McCone has cracked down on all that” (page 41).

Dulles notes this copy of the book and Fleming’s inscription to him in his 1969 work Great Spy Stories from Fiction. Although Dulles is recorded as having a full set of the James Bond novels all presented by Fleming, this is the only example Peter Harrington could trace on the market.

You Only Live Twice was the eleventh Bond novel, based on Japanese material that Fleming had gathered on his five-week foreign jaunt on behalf of The Sunday Times, the basis of his non-fiction Thrilling Cities (1963). It was the last Bond story published in his lifetime. The film adaptation, starring Sean Connery as Bond, was released in 1967.

A close friend of Fleming, Allen Dulles (1893-1969) served as director of the CIA from 1953 to 1961 under Eisenhower and Kennedy. He was consequently a significant figure in the early Cold War, overseeing the coup d’états in Iran and Guatemala, the Lockheed U-2 aircraft program, the Project MKUltra mind control program, and the Bay of Pigs Invasion. It is difficult to imagine a more appropriate presentation for the spy novel.

Dulles first encountered Fleming’s work when Jacqueline Kennedy gave him a copy of From Russia with Love in 1956. He sought a meeting with the author, one which did not in fact happen until 1959, when “over a suitably epicurean meal in London’s West End, they struck up an instant rapport. This was perhaps not suprising. Dulles was a warm Anglophile, while Fleming had got on very well with the Americans with whom he had worked during the war… both possessed a visceral conviction (opponents would call it paranoia) that the Russians were plotting night and day against the West” (Moran, p. 211). They maintained correspondence until Fleming’s death in 1964.

Yet the presentation represents more than just a cordial relationship between the two intelligence experts. Dulles was a great champion of the Bond novels in America, actively promoting the novels in the American press as a means of promoting public support for secretive intelligence agencies. This raised eyebrows among certain of his peers, who viewed the Bond novels as a salacious and populist misconstruction of intelligence work. But as Moran has argued, “Dulles liked Bond because the series was an unashamed celebration of the spy business. Despite being something of a blithe anachronism, a throwback to a time when spies dressed for dinner and crude racial stereotypes were socially acceptable, 007 projected an image of Western intelligence services as a noble-band of decisive and courageous patriots, fighting an enemy in the Soviet Union, that possessed a kind of wanton, undiscriminating belligerence” (ibid., p. 209).

Fleming himself interpreted his creation in the same way, once saying that Bond was the intelligence community’s “strong right hand” in the fight against communism (ibid.). Bond offered popular respect for the CIA’s work, especially at a time when the Soviet shooting down of the U-2 Spy plane and the failed Bay of Pigs invasion under Dulles’s watch (he had to resign over the latter) led to claims that the agency was ineffective and poorly run.

After Dulles’s death, the CIA impounded his private papers, finding with some shock that in Dulles and Fleming’s correspondence the former revealed much sensitive information to the latter, and that Dulles actively sought Fleming’s advice on intelligence matters. He even funded research into gizmos from the books, including a spring-loaded knife embedded into a shoe, and was thrilled to find that it worked. Moran comments on the significance of their relationship.

It is well known that spy fiction authors claim to draw inspiration from the real intelligence world. But the relationship between Dulles and Fleming shows that real intelligence also finds inspiration in spy fiction, for their public presentation, for technologies, and for their heroic self-image. It dispels any lingering notion that Bond is of no significance to historians.