Charlotte Perriand – Modern Love

The unsung French designer Charlotte Perriand is celebrated in an exhibition at the Design Museum in London, exploring the central role she played in shaping 20th-century modernism

In the course of her career the French designer Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) was described as fiercely independent, feisty and free spirited.

Early on, such characteristics allowed her to brush off revered Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s infamously brusque response to her early application to work with him – “we don’t embroider cushions here” – and give modern design one of its greatest and, until recent years undoubted unsung, heroes.

With a lifetime that spanned the 20th century, Perriand was a thoroughly modern denizen of the epoch – instrumental in shaping its character and appearance. An exhibition opening this month at the Design Museum, Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life, shines a spotlight on her continuing influence and work, confirming her deserved place as a giant in the century’s design story.

RAISE THE BAR

Despite Le Corbusier’s earlier rebuff, Perriand’s obvious talent soon captured the celebrated architect’s attention at the annual Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1927, where she recreated the distinctly modernist interior of her own small apartment in Saint-Sulpice, entitled Bar sous le Toit (Bar under the Roof).

One visiting critic wrote: “One cannot imagine anything fresher or more youthful.” Evidently, Le Corbusier was equally impressed by her mastery of metal furniture and use of materials ranging from aluminium and chrome to glass and leather – all set to become ubiquitous design motifs of the ‘machine age’.

She was soon bringing these skills to bear at Le Corbusier’s studio, as evidenced in her notebooks on display at the Design Museum, which reveal her role in the development of early tubular steel furniture with Le Corbusier and his cousin, the architect Pierre Jeanneret.

While Le Corbusier may be the most prominent of the trio, their decade-long professional relationship was highly collaborative, with Perriand’s input essential in realising his vision of ‘equipment for living’ designed to supplant traditional interiors and lifestyles.

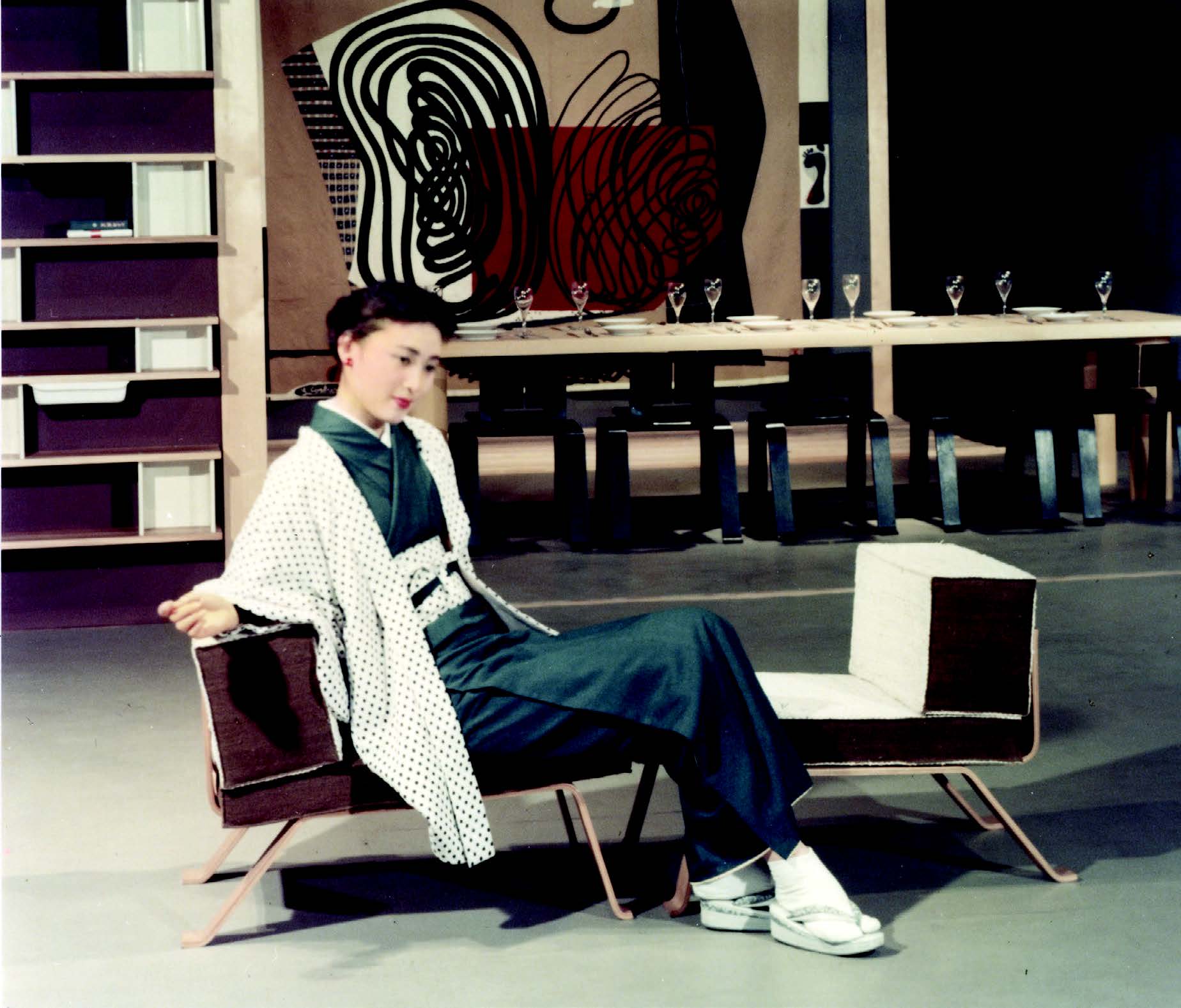

The atelier worked on numerous projects and products, ranging from oak and steel cabinets to dining tables. But some of the most memorable designs from the time were the three chairs that conformed to Le Corbusier’s principles of ‘machines for sitting’.

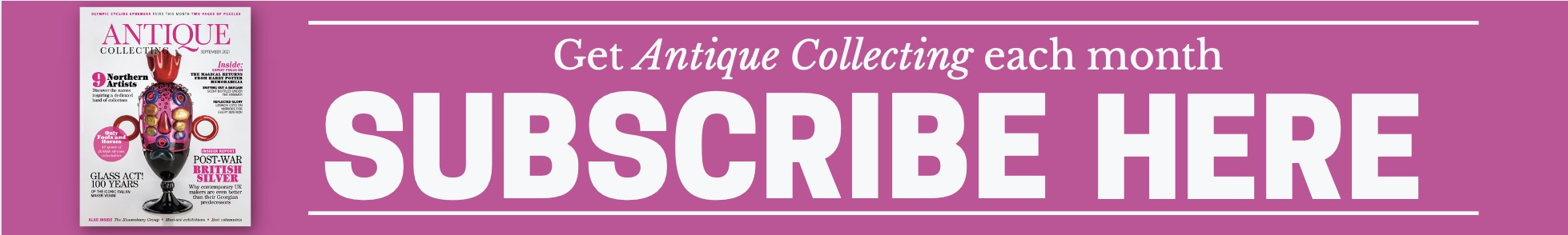

In 1928, Perriand’s response was to create three steel tube-framed design classics: the Basculante B301 sling-back chair for conversation, the Grand Confort LC2 armchair for relaxation and the Basculante B306 chaise longue for resting.

During the 1930s, Perriand’s work and designs began to reflect her increasingly leftist political viewpoint by taking on a more egalitarian approach in her use of materials and production techniques.

In her desire to create affordable pieces she turned away from more expensive materials such as chrome, in favour of naturalistic wood and cane, while employing traditional handcrafted techniques.

By the start of WWII, Perriand had stepped out from Le Corbusier’s shadow to establish herself as a designer in her own right. She formed a successful creative partnership with designer and architect Jean Prouvé, designing and producing prefabricated accommodation and items of furniture for the military.

EASTERN PROMISE

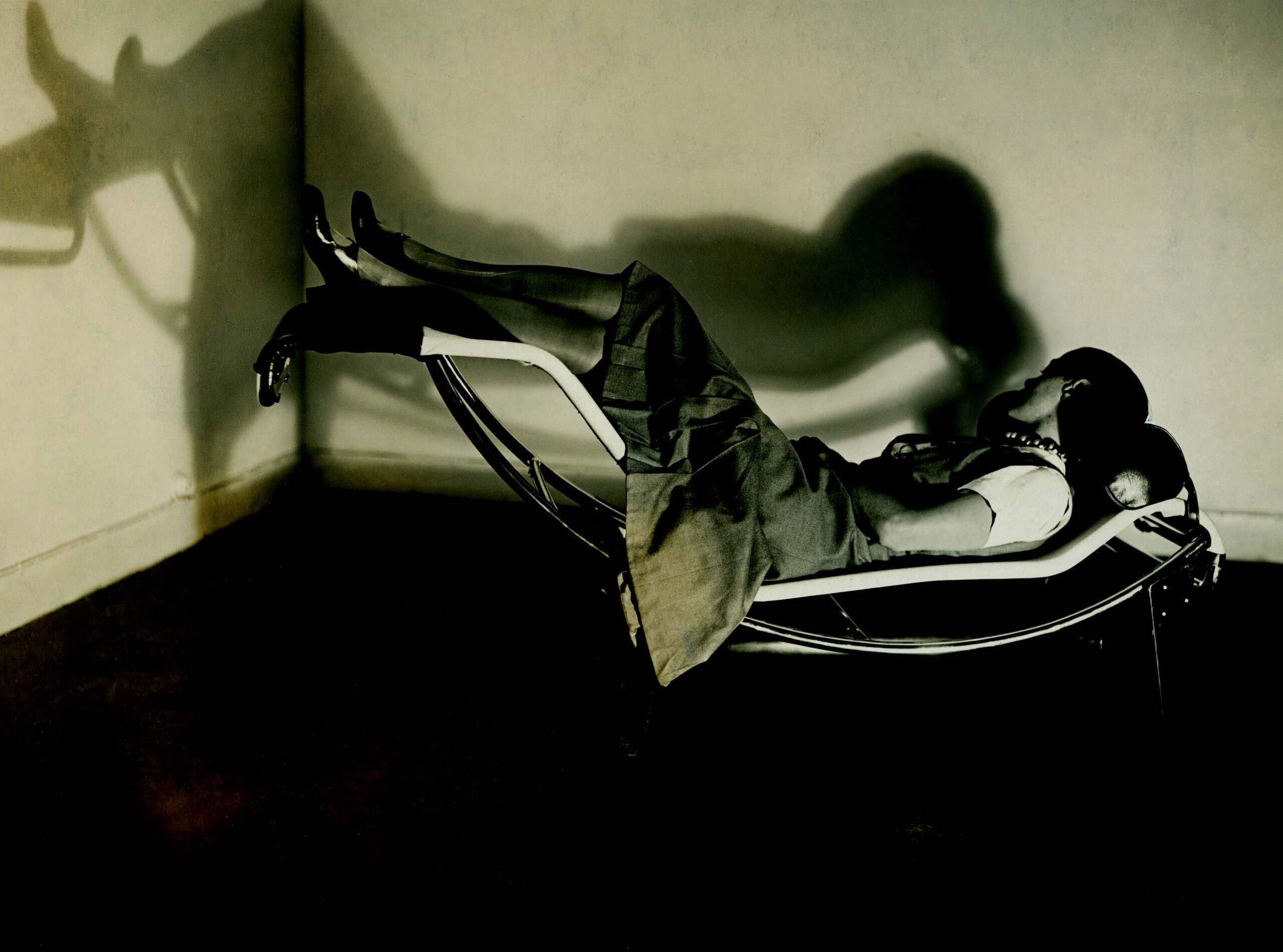

When Paris finally fell to the German army in 1940, Perriand travelled to Japan to advise on industrial design for the country’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. During her years of exile overseas, including three years in Japan followed by a further three years in Vietnam, she immersed herself in Eastern culture and sensibilities, making the most of the region’s materials, techniques and forms.

When she returned to France in 1946, Perriand embraced many of the new materials used in mass production, including aluminium, plywood and formica, and worked on diverse projects ranging from student accommodation to ski resorts, including her grandest and final project, the Les Arcs ski resort in France.

The project appealed to Perriand on a number of fronts: as a keen skier, devotee of the outdoors, and giving the opportunity to meet the challenges of construction in mountainous terrain.

Since her death in 1999, Perriand’s up to 300 furnishings have been prized by collectors and designers alike. On the rare occasions her original pieces appear on the market they are fiercely fought over before selling for thousands. For those with greater budgetary constraints, her designs are kept alive and in demand via the Italian furniture company, Cassina.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Q&A on Charlotte Perriand

Justin McGuirk, chief curator at the Design Museum explains why Charlotte Perriand’s work deserves to be better known

Q What most excites you about the exhibition?

A It’s an opportunity to present the work of one of the most important women designers of the 20th century. I mention the fact she was a woman only because there have been so few female modernist designers. We also make the case that Perriand wasn’t just a furniture designer but a spatial thinker – she was an early example of what, today, we would call an interior architect.

Q How did her career reflect changes in the modernist movement?

A Perriand began as a dogmatic modernist, championing industrial materials such as steel and glass. But in the late 1930s, alongside several other modernists, she turned against metal and ‘the machine age’, which was increasingly associated with militarisation and the growing rise of fascism.

Instead she turned to wood and the organic shapes she found in nature. But later she reconciled the two positions, finding the harmony in industrial sheet metal and handcrafted wood. It was in this balanced position that she found her true voice.

Q Was she a design progressive?

A Absolutely, and in several ways. Firstly she was a pioneer of tubular steel furniture in the 1920s, alongside Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe. She was also influential in the way she used storage systems to divide up interior space, keeping interiors open and flexible.

She was certainly ahead of her time in the way she designed modular shelving systems that gave the buyer options on how they could be assembled, making the owner part of the design process.

Q What was her creative process?

A Her notebooks on display at this month’s exhibition show how Perriand worked through particular problems of design or production. They also reveal how she studied the furniture market of the 1920s for solutions, pasting in adverts for products that she could either learn from, or reject.

Q Why is she so admired?

A Well, firstly there’s her talent. Also she made a name for herself in what was a male-dominated world. But she was also a dynamic and fun-loving person, and you can’t look at her life without seeing that energy and charisma.

Q Who, or what, were her most important influences?

A Le Corbusier’s principles of modernism, including the notion of furniture as ‘interior equipment’. Another important influence was Kakuzo Okakura’s The Book of Tea (1906) exploring Japanese aesthetics. In particular Perriand was drawn to Okakura’s concept of the vacuum, a sense of spatial emptiness. She sought that sense of space in all her interiors.

Q How far did Japan influence her?

A I would say two factors affected her deeply: the quality of the craftspeople in Japan and the sense of space in traditional Japanese homes – she was impressed by the orderly emptiness, and the flexible use of rooms for different functions.

Q How did she feel about the process of collaborating with other designers?

A Perriand was a highly collaborative designer, something I have tried to communicate in the exhibition. She saw the modern interior as a synthesis of industrial design, architecture and art so it is no wonder she sought out collaborations with architects and artists. As a very social person, she also enjoyed the process of collaboration.

Q Did her designs redress the role of women in society?

A Perriand once said: “Better to spend a day in the sun than dusting our useless objects.” This is one reason she was so obsessed with storage, she wanted to free up the space of the home and consequently the housewife’s time.

Q Did she step out of Le Corbusier’s shadow?

A It’s only really the early period of her career when she was under his shadow. From the late 1930s she clearly became a designer with her own voice and her own ideas – with half of a century of her career still to unfold. While she has been overshadowed by her male counterparts, the exhibition presents her not only as a brilliant designer who deserves wider recognition, but as a natural collaborator and synthesiser.

Q Choose one piece which most represents her design aesthetic

A The brightly-coloured bibiliotheques, with their modular steel elements which could be arranged in different ways are modern, colourful, and adaptable. They were also of their time and ahead of it.

Q What would Perriand make of the prices her pieces currently demand?

A I think she would be horrified. She was trying to reach the everyman, not the elite. Her bookcases, for example, were most commonly used in student dormitories, not luxury homes. But this is the nature of a burgeoning collectors’ market, with a limited supply of original pieces.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life

This month, the Design Museum shines a spotlight on the life and career of Charlotte Perriand, marking 25 years since the last significant presentation in London.

The exhibition reveals Perriand’s creative process through sketches, photographs, prototypes to the final design. It also charts her journey from the modernist machine aesthetic to her later architectural projects.

In three sections: The Machine Age, Nature and the Synthesis of the Arts, and Modular Design for Modern Living, it traces Perriand’s early furniture to her design for the Air France office in London in 1957.

Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life runs until September 5 at the Design Museum. For more details visit www.designmuseum.org

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Designs in Demand

Elie Massaoutis, Phillips’ head of design, France, reveals the strength of demand for Charlotte Perriand’s designs.

As a major figure in 20th-century design and a pioneer of modernity throughout her 60-year career, Charlotte Perriand helped define the new art of living. Today, her forward-thinking designs continue to appeal to contemporary collectors and designers.

TOP TABLE

The scarcity of pieces from the first period of Perriand’s career from the 1920s explains the stellar prices achieved at auction over recent years, with the trend continuing to go up. One of Perriand’s rare ‘free-form’ desk from 1939, presented at auction in 2017, currently holds the world auction record for her work. Estimated at £260,000-£350,000 it sold for £600,000. Offered with its original invoice, the desk ignited great attention from collectors worldwide.

Prior to that, Perriand’s ‘table extensible’, which she unveiled at the first exhibition of the French Union of Modern Artists (UAM) in 1930, held the world auction record for a work by the designer from 2009 to 2017. Estimated at £200,000-350,000, it sold for £430,000 at Sotheby’s, Paris in 2009.

At auction, factors such as rarity, impeccable provenance and traceability help produce record results for Perriand’s designs. In fact, buyers are likely to pay over the odds for exclusive pieces which have achieved these criteria.

JAPANESE INFLUENCE

During the period when she worked with the architect and designer Jean Prouvé, Perriand went on to manufacture mass-produced furniture influenced by the Japanese aesthetic.

From this era, her most notable designs were those which combined different elements and materials, perfectly illustrated by her bookcases La Maison du Mexique and La Maison de la Tunisie .

Phillips achieved record prices for these models back in 2007, selling a Mexique bookcase for £115,000, This was followed by a Tunisie bookcase which fetched close to £100,000 in 2016. We continue to see a steady increase in prices, with such models now selling for between £150,000-£200,000.

RARE APPEAL

During the years of post-war reconstruction, many of Perriand’s designs were produced on a much larger scale, setting them apart from other designs.

Distinguished by the use of exotic woods and more precious and luxurious materials, these later pieces continue to generate great interest in the saleroom.

Significantly rarer, often unique and hailing from special commissions, these are the designs that are more likely to increase in value in the years to come.

As an architect, designer and multi-talented artist, Perriand’s work continues to attract enthusiastic collectors as it anticipates current debates, in particular the importance of nature and the role of women in our society.