Tea chests and caddies – the essential guide

Nothing sums up the British way of life like a cup of tea. Author of The Story of British Tea Chests and Caddies: Social History and Decorative Techniques Gillian Walkling reveals how the 18th-century Midlands was central to the manufacture of tea chests and caddies

Tea chests and Caddies

When Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on September 25, 1660: ‘I did send for a Cupp of Tee (a China drink) of which I had never drunk before’, he could not have imagined that this simple infusion of leaves in hot water would one day become Britain’s national beverage and would be consumed on a daily basis in households throughout society.

The number of community tea parties organised to celebrate the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee is testimony to both its ‘Britishness’ and its enduring popularity.

It is often said that Catherine of Braganza was responsible for introducing tea to Britain when she married Charles II in 1662, but this is not so. It was first advertised for sale – as a medicinal drink – in a London coffee house in 1658. Nevertheless, by drinking tea at Court, the queen undoubtedly encouraged the habit, and tea-drinking very quickly became a social phenomenon.

The brewing of the tea evolved into a ritual, for which various accessories – most importantly Chinese porcelain teawares – were considered essential.

Expensive brew

Initially, tea was extremely expensive, having been brought all the way from China on East India Company ships and then subjected to a high import duty. It was soon apparent that a designated container was needed for its domestic storage, partly to keep it fresh and partly to protect it from the hands of pilfering servants.

Before long, pairs of silver or tinplate flask-shaped tea canisters – one for green and one for black tea – were being made, and similarly shaped porcelain canisters were being imported from China. In the early 18th century, these canisters were sometimes accompanied by a container for sugar, and the items were placed in a lockable ‘tea-box’ or ‘tea chest’.

Tea chests, like the one above, were made in this format throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, although in about 1780 the sugar container was generally replaced by a glass sugar bowl. (Note that these bowls are not for mixing tea leaves, as is often stated.)

The popularity of the tea chest was challenged in the late 1760s by the tea ‘caddy’, a box with one or two fixed interior tea compartments with removable lids. Caddies were smaller than chests, and a favourite with ladies.

Many were sold as gifts or souvenirs. Today, both chests and canisters are often incorrectly referred to as ‘caddies’.

Heart of England

Being a great status symbol for their owners, tea chests and caddies were considered important pieces of furniture, with both Thomas Chippendale and George Hepplewhite including designs for them in their celebrated pattern books.

The largest number were constructed wholly of wood and were made by cabinetmakers, the most fashionable of whom were based in London. However, during the second half of the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution taking place in England’s Midlands resulted in the emergence of a range of tea containers with a very different appearance, produced by craftsmen using some exciting new, or improved, techniques and materials.

At the centre of these developments was Birmingham, a town already famous for its metalwares and its production of small luxury items known as ‘toys’. One of the first techniques to be exploited (but not invented) there was japanning – a process simulating Oriental lacquerwork. It involved the application of varnishes and painting and gilding, all interspersed with stoving (baking in an oven). Japanning was first applied to tinplate, and later to papier mâché too.

Initially, the metal pieces were quite sophisticated – some chests housed silver canisters – but competition from the flourishing papier mâché market gradually resulted in the metal japanners’ focus turning towards slightly less glamorous pieces, and eventually to cheaper, more utilitarian goods.

Henry Clay

The outstanding 18th-century exponent of japanned papier mâché in Birmingham was Henry Clay, who patented an improved way of making ‘paper-ware’ in 1772. The method involved pasting and layering together sheets of specially-made paper, and then stoving them to make large laminated sheets.

Although widely used for making coach panels, Clay found that the sheets were hard enough to work in a similar manner to wood, and also had a smooth surface suitable for japanning in the same way as metal; both of these features were ideal for producing boxes such as chests and caddies.

The process was adapted to make the oval caddies that were especially popular in the 1780s and 1790s by wrapping the pasted paper around an oval wooden form before the stoving. Clay’s very wide range of papier mâché products were extremely high-quality, with some superb painted decoration, and large numbers of finely-decorated oval caddies were included in his repertoire.

Ivory veneer

Birmingham was particularly well known for its workers in ivory, tortoiseshell, and mother-of-pearl, and it was not unusual for individual workshops to employ craftsmen to work with all three materials.

Despite the importation of ivory tea chests from China and India, it seems that ivory was not employed to make them in Britain. It was, however, used extensively during the 1780s and 1790s to veneer small caddies. These were mostly octagonal in shape, with tented or flat lids and some form of decoration on the front, either a plaque for initials, a framed medallion, or a jasper cameo. Their edges were usually strung with contrasting tortoiseshell. Many had additional decoration of mother-of-pearl and silver or gold piqué work.

Tortoiseshell designs

Similar caddies were veneered with tortoiseshell (actually turtle shell), with ivory stringing. Being a pliable material when heated, tortoiseshell was often pressed into moulds to create patterns in its surface. Paint or coloured foil was sometimes used as a backing to alter or enhance its colour.

Much more difficult to work with, and generally only available in much smaller pieces, was mother-of-pearl, although some exceptional chests with sizable carved pearl panels were imported from China. While similar to their ivory and tortoiseshell counterparts, mother-of-pearl caddies are relatively rare.

Enamel caddies

Birmingham was also home to some accomplished enamellers, as were nearby Wednesbury and Bilston. The basic technique of enamelling involves fusing a coloured glass to a metal base through firing, and then painting the resulting plain surface with finely powdered glass, coloured by the addition of metal oxides; each colour requires a separate firing, during which the colour is liable to change, thereby requiring a high level of skill.

Some superb enamel tea chests fitted with matching canisters were painted in this way during the 1760s and 1770s. Although enamelling was by no means a new technique, it was 18th-century Midlands craftsmen who mastered the technique of transfer-printing, thereby simplifying the decorating process. Single-coloured transfer-printed canisters can be found in chests with matching decoration, as well as in some fine examples made of gilt-metal, framing panels of aventurine glass or papier mâché.

Surprisingly, enamel caddies are uncommon; those that do appear tend to be oval in shape with raised lids fitted with a gilt-metal handle.

Ceramic canisters

Transfer-printing is much more often seen on tea canisters produced at the Staffordshire potteries. Ceramic canisters are something of an anomaly, as they seem to have been designed to be free-standing and have no lock; no British examples fitted in a chest have been found.

However, earthenware and stoneware canisters, with various glazes and forms of decoration, were made in great quantities. Many were press- or relief-moulded, while others were painted with coloured enamels, or decorated with prints. Some had additional gilding. The majority were of basic flask shape, but square-based, cylindrical and vase-shaped examples were also made. The most successful Staffordshire potter was undoubtedly Josiah Wedgwood, whose experiments with new bodies and glazes lead to the production of fine and sophisticated pottery capable of rivalling the new British porcelain wares being made elsewhere.

Most successful, and widely imitated by others, were his cream-coloured ‘Queen’s Ware’ (creamware), perfected in 1763, and his ‘Pearl White’ (pearlware), launched in 1779. The latter had a smooth white finish very similar to that of Chinese porcelain, and pearlware tea canisters often have blue-and-white Chinese-style decoration.

Glass canisters

Last but not least of the Midlands-made tea containers are those made of glass. There had been glassmakers in the Stour Valley – an area rich in the essential raw materials – since the 16th century, and other businesses were subsequently established in Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and Dudley.

It was in Dudley and Stourbridge that glass makers first began experimenting with steam-driven glass-cutting lathes in the 1790s. Unfortunately, as glass was hardly ever marked by its makers, and as most factories were producing very similar items, it is almost impossible to attribute individual pieces firmly to any specific area, but it is likely that some of the many and various glass tea canisters, chests, caddies and sugar bowls that came onto the market were made in the Midlands factories.

Some pairs of opaque-white glass canisters, with enamelled decoration and gilt-metal enamel cap lids are attributed to the area, as are some very fine gilt-metal chests with panels of aventurine glass.

The canisters, chests and caddies described here represent only a fraction of the vast range of tea containers made between about 1670 and 1900. Wooden examples are almost infinite in their variety of shapes and styles, and huge numbers were made in silver, Old Sheffield plate and pewter. Many wooden pieces were finished with japanned decoration, others with penwork or rolled paper, and distinctive souvenir caddies were produced in Tunbridge Wells, and in Mauchline and its environs in Scotland.

Napoleonic prisoners-of-war carved caddies in bone or covered them with straw work, while ladies decorated them with feathers or shells. Some were constructed of wood from Shakespeare’s mulberry tree or Nelson’s flagship, and numerous pieces were made in the forms of fruits, houses, books or coal scuttles. Drawers containing canisters were fitted in tables and chests of drawers, and in the 19th century teapoys proliferated.

Collecting guide to tea chests and caddies

For the collector there are countless opportunities, with examples to suit all pockets. However, there are caveats. Although their owners held them in high esteem, during their lifetime caddies will have been well-used, and many are no longer in prime condition.

Over the years there were conventions for handles, hinges, feet, escutcheons, interior linings etc., so make sure you know what to expect. Look out for replacement hinges and locks, and for repairs to veneers or other surface decoration. Restoration, even when done well, will affect value.

Be aware also of very convincing fakes, especially in ivory, tortoiseshell and enamel caddies. If buying on the internet, check all the details and, if spending a large sum, consult an expert in the field before making your purchase.

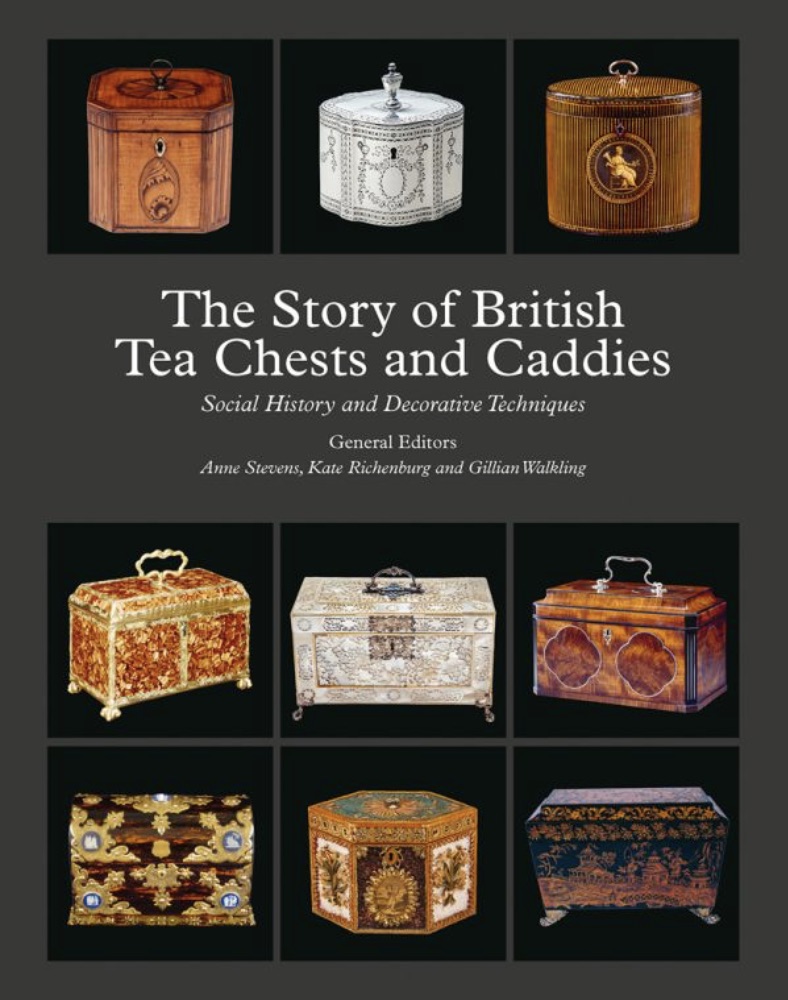

The Story of British Tea Chests and Caddies: Social History and Decorative Techniques. General Editors: Anne Stevens, Kate Richenburg and Gillian Walkling is published by ACC Art Books priced £55.

The Story of British Tea Chests and Caddies: Social History and Decorative Techniques. General Editors: Anne Stevens, Kate Richenburg and Gillian Walkling is published by ACC Art Books priced £55.