JD Fergusson – A life in colour

To mark the recent 150th anniversary of the birth of the Scottish Colourist JD Fergusson, the Edinburgh auction house Lyon & Turnbull hosted a sale of Scottish art with a special focus on his work. Alice Strang reports on his career and lifelong love of France

The Life of JD Fergusson

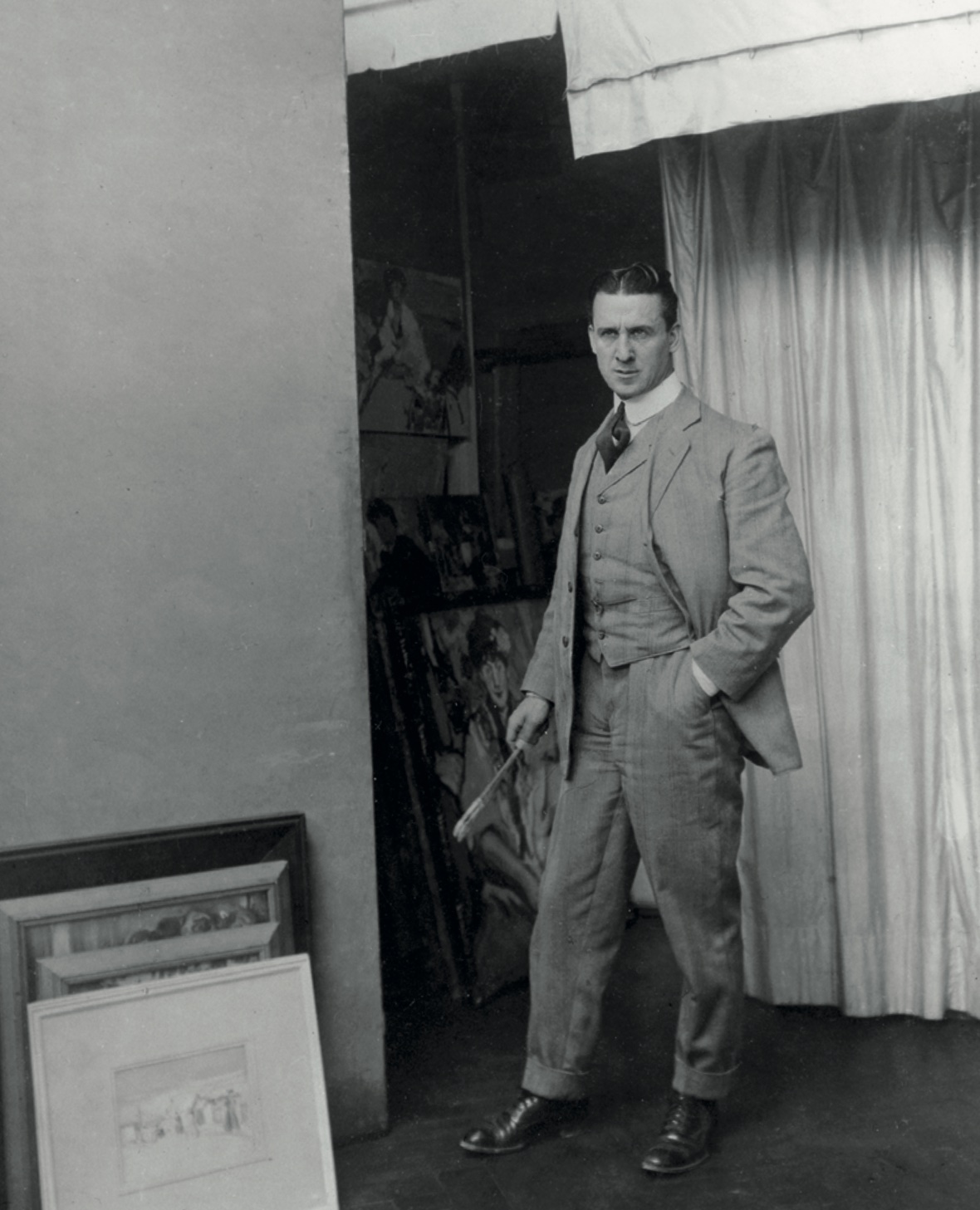

This year’s anniversary has seen a number of events devoted to the influential artist John Duncan Fergusson (1874-1961) one of the most important Scottish painters of the 20th century.

A new permanent display of his work has opened at Perth Art Gallery and, following its exhibition in partnership with the Fleming Collection A Scottish Colourist at 150: John Duncan Fergusson, Lyon & Turnbull recently hosted a sale of Scottish art with a special focus on his works at its Edinburgh saleroom.

The exhibition traced Fergusson’s career from his emergence as an artist of sophistication in Edwardian Edinburgh, to his role in the development of modern art in Paris. It also explored the inspiration he clearly found in the Scottish Highlands and his joy in portraying the pupils of the summer schools held in France by his wife, the dance pioneer Margaret Morris (1891-1981).

Fergusson’s International reach

Fergusson was born in Leith, near Edinburgh and is one of four artists, along with Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883-1937), George Leslie Hunter (1877-1931) and Samuel J Peploe (1871-1935), known as the ‘Scottish Colourists.’ They are revered as masters of modern Scottish art with their works often the highlights of collections in this field.

In addition, collectors of both modern British art and modern European art are also drawn to Fergusson, who has the most international reputation of the group.

This is partly due to key periods he spent living in Paris before WWI and during the 1930s, as well as in London between 1914 and 1929. As the longest-lived of the Colourists (the others died before the start of WWII, while Fergusson lived to the ‘60s) he also played an important role in the Scottish art world after WWII, from a base in Glasgow; he died in the city in 1961. Fergusson’s international standing is epitomised by his election as a sociétaire, or member, of the progressive Salon d’Automne, in Paris in 1909, in recognition of his contribution to the modern movement. Indeed, the six years he spent in the city, between 1907 and 1913, provide the foundation of his standing beyond Scotland, underpinned by his lifelong pride in being a Scot.

Move to Paris

In 1907, Fergusson decided to move from Edinburgh to Paris. The trip was made possible thanks to an inheritance following his father’s death and was encouraged by meeting the American artist, Anne Estelle Rice (1877– 1959), in Paris-Plage in the summer.

The pair began a romantic and professional relationship which lasted until 1913. Fergusson declared “Paris is simply a place of freedom” and settled in Montparnasse, the celebrated artists’ quarter.

Fergusson embarked on a series of vibrant Parisian street scenes, such as Boulevard Edgar Quinet, where he rented his first studio in the French capital. His excitement about his new surroundings is clear, as he revelled in the depiction of the city’s architecture and citizens.

His brushwork became bolder and his palette brighter in deftly-captured scenes of daily life. With a confident command of modernist technique, form is indicated by way of distinct brushstrokes, whilst highlights of bright colours, including red and turquoise, enliven the composition and suggest a response to the brighter light of France compared to that of Scotland.

In his memoirs, Fergusson recorded: “I immediately found there, what the French call an ‘ambience’ – an atmosphere which was not only agreeable and suitable to work in, but in which it was impossible not to work!”

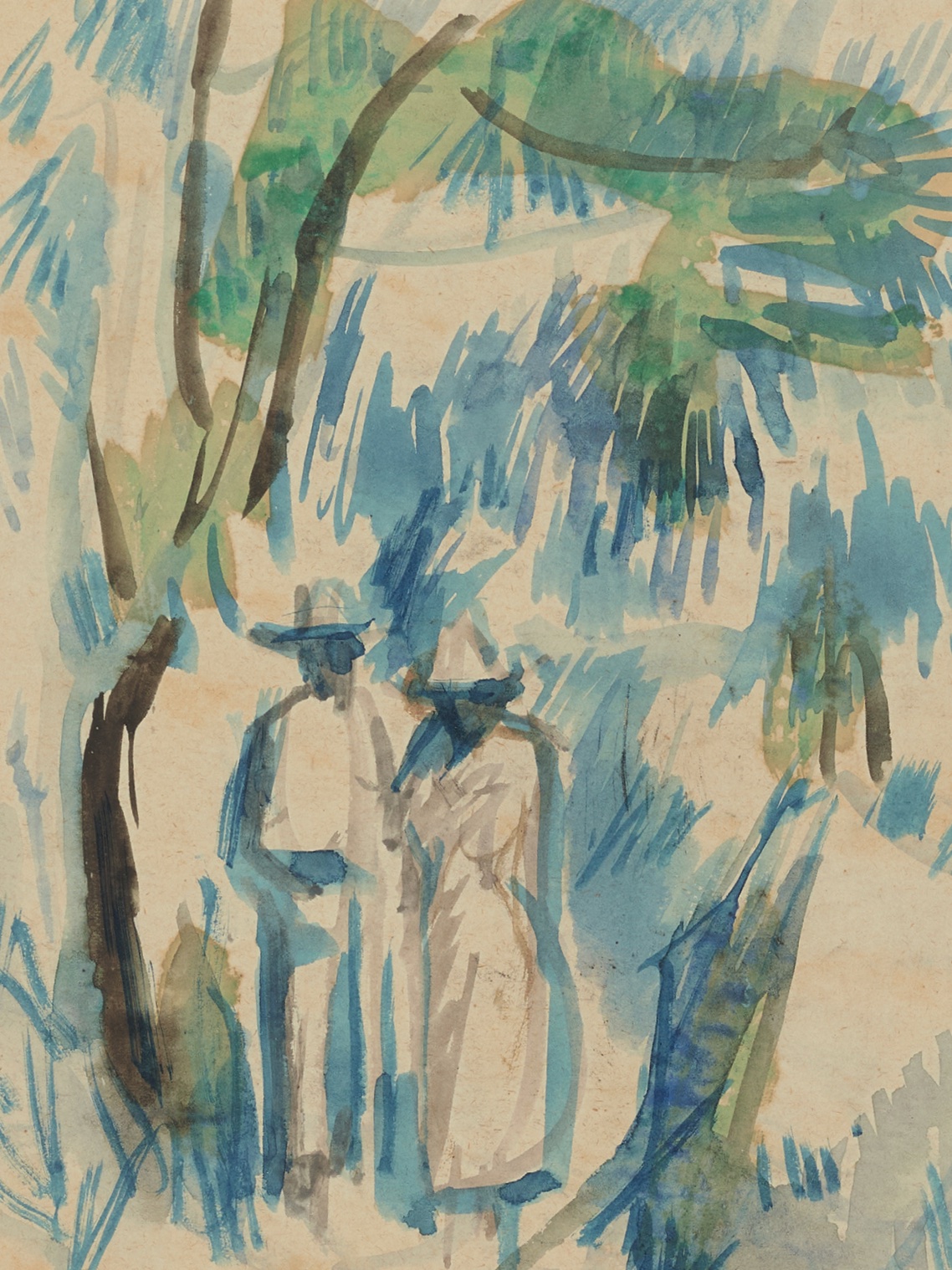

Fergusson also indulged his love of drawing and sketching. He rarely ventured outside without a sketchbook and worked at speed and with spontaneity in front of his subjects, usually capturing them in charcoal or watercolour.

‘Rhythmist’ group

One of the highlights of the sale was Fergusson’s Rose in the Hair, painted in 1908 the year following

his move to Paris. It is a tour de force example of how his practice flourished in the context of the very birth of modern art. He absorbed and evolved the latest developments in the work of artists including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and André Derain. He and Anne Estelle Rice, became key figures in the Anglo-American ‘Rhythmist’ group, known for their progressive arts journal Rhythm. The controlled, realist technique of the portraits Fergusson had made in Edinburgh gave way to the gestural, suggestive brushstrokes seen here.

Feminine confidence, beauty and style remain but are now celebrated by way of layered colours and a sense of spontaneity. Fergusson kept Rose in the Hair all his life and selected it for inclusion in a solo exhibition of his work staged at L’Institut Français d’Ecosse in Edinburgh in 1950.

Dance pioneer

It was in Paris in 1913 Fergusson met his long-term love, the dance pioneer Margaret Morris (1891-1981). Soon after meeting, their personal and professional lives became interwoven. Later that year they left the capital for the Cap d’Antibes, Fergusson saying: “I had grown tired of the north of France; I wanted more sun, more colour; I wanted to go south.”

But the outbreak of WWI prompted a move to London. Morris had a dance school and theatre in Chelsea and established the Margaret Morris Club. This became a popular meeting place for the creative avant-garde, from poets and composers to painters and sculptors. Fergusson thus found himself in the centre of the English art scene and lived in the city for 15 years.

South of France

The years 1929 to 1939 saw Fergusson back in Paris. Bathers, Antibes of 1937 encapsulates the active, outdoor lifestyle he and Morris enjoyed during the summer schools she ran in the south of France.

In 1923, the school was held in Antibes for the first time and the following year Morris and her dancers posed for photographs which were used to launch the first summer season at the Cap, which is now one of the world’s most luxurious resorts.

Morris and her pupils dancing barefoot in pine forests and on beaches, as well as swimming and sunbathing, provided Fergusson with endless inspiration for his work. In his turn, he taught them to draw and paint and to design theatre sets and costumes.

Bathers, Antibes depicts some of Morris’s pupils at a bathing place cut into cliffs. The red forms are handrails and ladders which were installed in the warmer months. As she recalled: “Everyone bathed off the rocks and afterwards sun-bathed in the woods or on the rocks. When they got too hot, they dived into the sea again. Fergus [sic] got much inspiration and did hundreds of sketches over the years, from which he painted many pictures.” An art deco stylishness can be seen in this sun- kissed image of healthy, tanned women.

Back to Glasgow

On the outbreak of WWII Fergusson and Morris relocated to Glasgow, which Fergusson felt to be the most Celtic Scottish city, an important accolade from an artist who was endlessly proud of his Scottish ancestry. In 1940, Fergusson and Morris were co-founders of the New Art Club, out of which emerged the New Scottish Group of painters.

Following Fergusson’s death in 1961, Morris established the JD Fergusson Art Foundation to secure his legacy and to support living artists. The Foundation’s aims were achieved with the opening of The Fergusson Gallery in Perth in 1992 and the launch of the JD Fergusson Arts Award Trust in 1995.

The radical work of Fergusson and the other Scottish Colourists, truly enlivened the Scottish art scene with the dynamism, vibrancy and colour of European Modernism – in doing so they breathed new life into Scottish art.

Talented sculptor

It was during WWI that Fergusson turned to sculpture. It was a new, provocative way to manipulate and experiment with the human form and the physicality of his sculpture is as exciting as the colour in his painted works.

Although relatively little is known about his sculptural work, it remains an important part of his oeuvre, and demonstrates his distinctive artistic identity and talent. Fergusson made and exhibited sculpture for more than 35 years, with a concentrated period of productivity from about 1918 to 1922. This coincided with a parallel development in the Margaret Morris Movement, the dance technique devised by his partner.

Eástre (Hymn to the Sun) of 1924 (cast 1991) is his best-known sculpture, not least because two posthumous editions of it exist. Fergusson made it in plaster in 1924, but kept it under his bed for three years before he could afford to have it cast in brass. Eástre is the Saxon goddess of spring and the rising sun. The work is believed to be a portrait of Morris, who devised a ballet of the same title inspired by the music of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Reflective brass was popular in the 1920s as a way to signify modernity.

Female form

Torse de Femme, 1918 (cast 1991) is perhaps his second best-known sculpture, not least because an enlarged cast of it was installed in Perth in 1994.

It is a powerful depiction of female physicality and embodies key themes in Fergusson’s sculptural practice: the cropped female form, an interest in non-Western sculpture and a sleek modernism, based on curves and planes with particular attention paid to the breasts, bottom and the base of the spine.

It pays testament to the sculptors with whose work Fergusson would have been familiar in pre-war Paris, such as Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Archipenko and Jacob Epstein. The angularity of form also relates to Vorticism, whose members Wyndham Lewis, Christopher Nevinson and Edward Wadsworth Fergusson knew through the Margaret Morris Club.

French influence

One of the loans to the exhibition at Lyon & Turnbull was Fergusson’s exquisite oil on canvas Jonquils and Silver painted in 1905.

It reveals Fergusson’s friendship with fellow Colourist SJ Peploe, whom he met in Edinburgh in about 1900. Both shared an admiration for artists including Édouard Manet and Diego Velázquez, whose work they saw in Paris in the 1890s and whose influence is clear as can be seen in this painting.

In a manner similar to that employed by Peploe in a series of contemporary still lifes, Fergusson set his props of Adam revival- style silver salts and a pepper pot on a white tablecloth, set before a dark background.

A sense of a refined lifestyle is emphasised by the inclusion of the jonquils, which represent a token of desire in the language of flowers. Fergusson’s technical virtuosity is clear, for example, in the depiction of the reflections on the surface of the silverware.

JD Fergusson at auction

Last year, a record was set for a work by Fergusson at auction when his 1918 painting Submarines and Camouflaged Battleship sold for £1,074,000, beating its estimate of £400,000-£600,000. Fergusson, who was given privileged access to the naval harbour because he was working under a military commission from the Ministry of Information’s Propaganda and Record Department, carried out a series of paintings of what he saw. He wrote to Margaret Morris: “I went down to Southsea last night, it was quite wonderful – really like the south of France … I go round the docks with the Commander man again today. We went round in a boat yesterday and it was very fine indeed to paint.”

The submarines and ships Fergusson found in the docks had all been kitted out in the striking, broken-form colours and shapes of dazzle camouflage. This was a unique camouflage style, devised by the English Vorticist painter Edward Wadsworth that made practical use of a Cubo-Futurist technique to distort a ship’s outline and confuse the visual rangefinders of enemy vessels.

But if six figures is beyond the collecting budget of most, Fergusson was also a prolific sketcher with a multitude of works on paper regularly making their way to UK (and French) salerooms – many of which are affordable.

Works on paper

Thoughout his career Fergusson loved drawing and sketching in charcoal and pencil with subjects ranging from self-portraits, to still lifes and women – often either nude or in a variety of hats. In 2021, nine of his sketches, ranging from his early academic studies in Edinburgh to his more mature ‘European’ technique went under the hammer at Lyon and Turnbull, with prices ranging from £2,000 to £4,000, the latter achieved by Flowers and Fruit, a pen, ink and wash of 1911 that relates directly to a handful of Colourist oils Fergusson painted between 1910 and 1912.

Where to see JD Fergusson and other Scottish Colourists

The charitable trust Culture Perth and Kinross is the custodian of the largest collection of artwork and personal, archival material belonging to JD Fergusson. In March, Perth Art Gallery opened a new exhibition called Fergus and Meg: A Creative Partnership made up of 40 paintings, drawings, and watercolours, including some of the artist’s best-known works such as The Grey Hat, Le Manteau Chinois and At My Studio Window. It will also feature important works by his wife Margaret Morris, as well as dance costumes, photography, and film.

National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh houses a significant collection of works by Fergusson and other Scottish Colourists. In Glasgow, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum is another institution with a notable collection, along with the city’s Hunterian Art Gallery.

Alice Strang is an associate director and senior specialist in modern and contemporary art at Lyon & Turnbull, the market leader in dedicated Scottish art sales. As senior curator at the National Galleries of Scotland, she curated its John Duncan Fergusson retrospective exhibition of 2013-2014 and edited the accompanying book. She is a BBC Expert Woman and a Saltire Society Outstanding Woman of Scotland