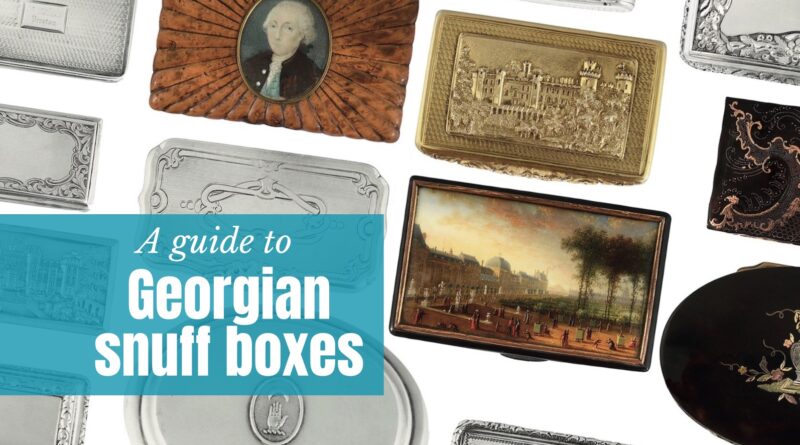

Georgian snuff boxes – the ultimate guide

Nothing enchanted a Georgian dandy as much as a well-crafted snuff box, Antique Collecting lifts the lid on a popular collecting area.

Georgian snuff boxes

Long before snuff came on the scene, at the end of the 16th century there was only one way to consume tobacco – for both men or women – and that was a pipe. But in 1792, with Sir George Rooke’s capture of a convoy of Spanish merchant ships at Vigo Bay heavily laden with 50,000 pounds of premium snuff (powdered tobacco) – all that was about to change.

When the captain and crew returned home, they set about selling the high-quality prepared snuff in several English seaports. It eventally made its way to the fashionable coffee houses of London where, even Samuel Johnson was persuaded to take up the new habit.

Before long snuff had taken society by storm all but relegating smoking tobacco to the lower classes.

Popularity of snuff

Snuff’s popularity spread like wild fire. In 1705, Beau Nash, Master of Ceremonies in Bath, banned smoking in the city’s public rooms. Fashionable residents soon followed suit, as did London society which looked to Bath for matters of taste.

It was essential etiquette for a gentleman to offer his snuff to acquaintances with great ceremony surrounding the exchange. A number of books were published on the subject. An anonymous pamphlet published in France, c. 1750, outlined the correct steps of the ritual for offering snuff in company which included the instructions: “Deftly gather a pinch of snuff with the right hand. Hold the snuff a moment between the thumb and finger before advancing to the nose. Bring the snuff to the nose. Inhale the snuff with both nostrils without grimacing. One may then sneeze, cough and spit. Close the snuff-box.”

In Britain, Queen Charlotte (known as “Snuffy” Charlotte) kept a whole room in Windsor Castle stocked with snuff. Other devotees included William Pitt, Beau Brummell, Viscount Petersham, the Duke of Wellington, Admiral Lord Nelson and the Duke of York, with the habit as popular among women as men.

Archives record Margaret Thompson of Westminster, who died in 1776, ordered in her will that “my coffin shall contain a sufficient quantity of the best Scotch snuff—in which I have always had great delight— to cover my body.” She requested the pall bearers should be “the six greatest snuff‐takers in the parish of St. James, who must wear snuff‐colored beaver hats instead of the usual black.”

Her maid was also directed to distribute during the funeral procession “a large handful of snuff every 20 yards on the ground and to the crowd.”

The art of snuff

Early on in the fashion, Charles Darwin refers to taking snuff from a box in the hall, hinting the habit was more behind-doors than a fashionable societal pursuit.

It is only during the period 1730-1775 that the size of the snuff box increased from 10-13cm (3-4in) as the the ‘art of snuff’ found its way into the finest and most fashionable European salons.

Snuff was kept in specially made boxes of various materials, designs and sizes depending on its use. The pocket snuff box, or day box, called a journée, contained a ration to last a day. It also had to fit comfortably in the palm of one’s hand.

The use of a hinged lid on the box minimized any spillage, and the lid had to fit very snugly to keep snuff dry. In addition, the box had to open to a precise angle that would permit easy access to the contents while allowing it to remain stable with the lid raised.

Originally made of carved wood, ivory, iron or silver, and known as a tabatière, gold snuff-boxes — often attractively enamelled — soon became the height of functional fashion. At the start of the snuff epidemic snuff boxes measured not much more than 5cm (21⁄2in) suggesting the habit was more novelty than obsession.

Lord Byron

Collecting snuff boxes also became an obsession among Georgian gentlemen. Lord Byron spent £500 on them in a single shopping spree (he later disposed of most of his collection to pay for his ill-fated campaign in Greece), while Viscount Petersham owned 365, a box for every day of the year, and ‘one that suited the weather.’

As snuff’s popularity reached dizzying heights so the box it was carried in soon became a status symbol and were given as tokens of love or friendship or a marker of military or diplomatic merit. Catering to this new consumer, large quantities of silver boxes were produced in Birmingham, makers also produced larger, more elaborate table snuff boxes.

Tobacco trade

Every schoolboy knows it was Christopher Columbus who first brought a few Cuban tobacco leaves and seeds with him back to Europe in 1492.

However, his travels in the New World discovered native inhabitants using the soverane herbe in a number of ways. Alongside smoking, it was variously chewed, eaten and sniffed.

However most Europeans didn’t get their first taste of tobacco until the mid-16th century, when adventurers such as France’s Jean Nicot – after whom nicotine is named – began to popularise its use. Tobacco was introduced to Nicot’s home country in 1556, Portugal in 1558, Spain in 1559 and England in 1565.

But it was not until 1612 when John Rolfe planted the first seeds of West Indian tobacco in Virginia, with a view to starting a profitable export business, that tobacco became an important element in British life.

Literary references to it date from the 1680s, the name derived from the Dutch, who referred to powdered tobacco as snuf, short for snuftabak, itself taken from the verb snuffen, meaning “to draw forcibly into the nostrils” and tabak, meaning “tobacco.”

Snuff was thought to have curative properties – even seen as an antidote to poison. Queen Charlotte took it to cure her headaches.

Nathaniel Mills

Silver boxes grew out of earlier snuff boxes with the main centre of production being Birmingham and the number of small workers making souvenir pieces.

Among the most prolific was Nathaniel Mills (active 1826-1850) whose designs were then, and remain today, among the most sought after.

Other active box makers in the city at the time alongside Mills – who registered the mark ‘NM’ within a rectangle at the Birmingham Assay Office in 1825 – were John Shaw (1795-1809) and Edward Smith (1833-1852), Matthew Linwood (1789-1806), T. Simpson & Son (1811- 1812) and John Bettridge (1829-1830).

Mills was notable for his innovative manufacturing techniques which included engine-turning, stamping and casting. His hinges were strong, with the corners and seams neatly soldered.

His oblong boxes were adorned with incurvate walls and engine-turned panels ranging in size from large table boxes, some 3 1⁄2 in (10cm) in length, to smaller ones up to about 2in (5cm) long.

A single-owner collection of snuff boxes, vesta cases and vinaigrettes, including earlier designs as well as those by Nathaniel Mills, amassed over 40 years went under the hammer at Catherine Southon’s Kent saleroom earlier this year. Find out more about future sale at www.catherinesouthon.co.uk

The importance of blends

Equally intricate were the snuff blends which saw the powder blended with various types of essential oils including lemon, rose, jasmine, lily of the valley, violet and musk to create a wide range of flavours. Alcohol such as brandy, bourbon and bordeaux were also popularly used, with recipes jealously guarded.

Some takers preferred to make up their own blend called “sorts” and often named after the maker, a popular blend being “Brummell’s sort.”

Snuff merchants, such as Fribourg and Treyer in the Haymarket, sprang up to cater to the growing market. Tobacconists also sold snuff handkerchiefs, usually silk edged with lace, and worn dangling from a sleeve. Dark colours were favoured over white to disguise any tobacco-stained spittle.

Castle-top snuff boxes

Another box with its roots in snuff boxes are versions known as ‘castle-top’ boxes produced between 1830 to 1865. Their popularity coincided with the expansion of the railway which opened up the country to middle-class Victorian tourists.

To mark the new day trippers’ visit, a trade in silver boxes, still used to carry snuff, visiting cards or vinaigrettes (which contained a sponge soaked in perfume to mask unpleasant smells) grew up.

Many were decorated with views of famous historic landmarks especially with royal connections such as Windsor Castle, Osborne House, or Balmoral, while historic views of Warwick Castle or Westminster Abbey were also popular. Souvenirs of places with literary associations were also sought after, such as Newstead Abbey one-time home of the Romantic poet Lord Byron, or Abbotsford House, which was the home of Sir Walter Scott. Even scenes of towns and villages which appeared in literature were popular.

Most ‘castle-top’ boxes were made by die stamping or repoussé, pushing the metal out from behind and using a stamp to create a scene in relief, the higher the relief decoration the harder they were to make.

Collecting castle-top boxes

Today, castle-top boxes are considered extremely collectable and remain among the strongest areas of the auction market for small silver objects.

Depending on the type of box or case, prices can vary from mid hundreds to more than a £1,000 and considerably more for a particularly rare example of a box by a sought-after maker.

If the view depicted presents an unusual view or aspect of a familiar subject, then the box will likely be more sought after by a collector and fetch a better price.

The same can be said of those boxes featuring rarer subjects, which appear less often. These include Wells Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral, Buckingham Palace (before the removal of Marble Arch) and Brighton Pavilion among others.

The record for a ‘castle-top’ card case stands at £9,800 which was for a very rare example of The Post Office, Dublin. Look out for rare examples such as Eddystone Lighthouse, Cornwall, which could fetch a similar amount.

Vesta cases

Adapted from the Georgian snuffbox, vesta cases (which derive their name from the Roman goddess of the hearth and home) make a delightful collecting area.

Early matches often could ignite from rubbing on one another and therefore required protection. Vesta cases were therefore designed to keep matches safe and, most importantly, dry, with their distinguishing feature being a ribbed surface, usually on the bottom for striking the match. Popular between 1890 and 1920, they were carried predominantly by the chain loop, to attach them to a double- ended Albert and then a waistcoat, which held a pocket watch on one side and a vesta case on the other.

Like the snuff box before them, vesta cases allowed for the demonstration of the owner’s wealth, personality and style and soon became a great accessory for the late-Victorian and Edwardian smoker.

In style and material they differed greatly with even Fabergé creating intricate guilloche enamel versions, along with Tiffany in New York and Asprey, in London.