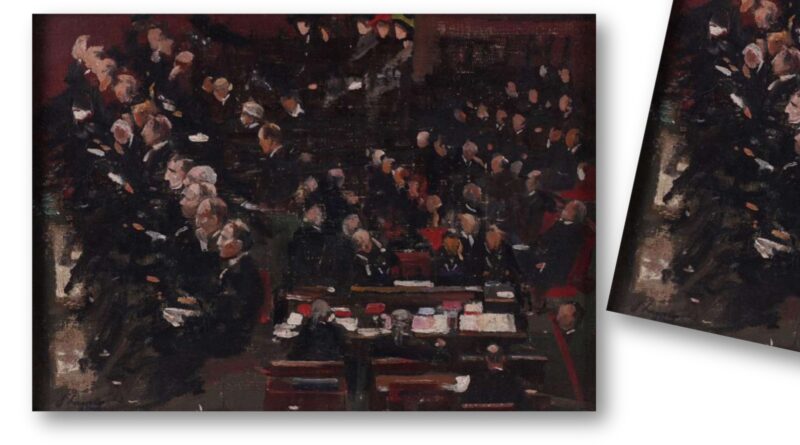

Sir John Lavery political study at Bellmans

A rare study for The Ratification of the Irish Treaty in the House of Lords, December 1921 by Sir John Lavery is set to sell in a November auction at Bellmans in London.

Sir John Lavery (Irish, 1856-1941) is best known for his portrait painting, but he was also well-respected for his ‘painting of contemporary history’ of which this is one of the most famous examples. The Ratification of the Irish Treaty in the House of Lords, December 1921 is not only one of his most important paintings, but also depicts one of the most significant moments in early 20th-century history.

Bellmans will be selling the signed study on November 21, 2024 as part of its Modern British and 20th Century Art auction. The studies rarely come up for auction and most can be found in institutions and museums – it is estimated at £20,000-30,000.

Michael Grist, specialist in charge of the sale, said: “As the artist himself observed, such works are ‘historical documents’ and it is a privilege to handle this painting, given in gratitude to fellow artist George Henry Paulin and comes to the market for the first time having been in his family ever since.”

On Friday, 16 December 1921 the Irish Treaty passed from the Commons to the House of Lords for ratification. It was the moment the British Empire changed – it had been expanding rapidly since the 1870s, but went into steep decline, and led to civil war in Ireland and ultimately the emergence of a ‘Free State’.

Sir John Lavery had sought the assistance of Sir Patrick Ford and Lord Birkenhead in obtaining permission to paint while the House was in session and arrived well prepared. Taking his seat in the centre of the Strangers’ Gallery, directly facing the thrones, he had come equipped with a ‘pochade’ box, and an ample supply of 10 x 14-inch canvas-boards, primed in burnt umber.

In 1921, Lavery was in his mid-sixties, his illustrious career began over 30 years earlier when, as a Paris Salon medallist, he was commissioned to paint The State Visit of Queen Victoria to the International Exhibition, Glasgow, 1888 (Glasgow Museums). One of the first featured artists at the Venice Biennale and an Academician, he had been knighted for his services as an Official War Artist. Although known as a portrait painter, Lavery was also renowned for his ability to capture the specific newsworthy occasion.

That early royal reception in Glasgow lasted no more than 30 minutes, but his job was not only to record the scene, but also to portray each of its 254 participants – a task that took two years to complete. Something of the same challenge lay before him in December 1921 when Earl Morley rose in the Lords to present the Irish Treaty Bill. Lavery could not know in advance how long he would have, so he must work quickly, roving his eye to either side of the house, catching profiles from the seated members. These vital jottings were not composed as pictures; they were fragments to be brought together in the studio.

His studio at the time was at Cromwell Place in South Kensington, Bellmans’ London office, and both he and his wife were very interested in Irish politics. When Ireland sent a delegation to London to negotiate for Irish independence, they hosted informal suppers and Lavery painted some of the delegation. Lavery’s own views on Irish independence were clearly declared in a letter to his friend and pupil, Winston Churchill, then Minister for the Colonies. He wrote that he believed that Ireland ‘…will never be ruled by Westminster, the Vatican, or Ulster, without continuous bloodshed … and [that] leaving Irishmen to settle their own affairs is the only solution’ (McConkey 2010, p. 154).

The sketch coming up for auction at Bellmans is a recently rediscovered missing link in the series, the artist catches the heads of three women spectators in the Strangers’ Gallery, dropping to two series of members’ rows taking us down to the floor of the house and what may be the head of Morley – a mere dab of flesh colour.

Then in the foreground, directly beneath where he was sitting, we see the barristers’ desk with its litter of papers, facing the Lord Speaker’s and Judges’ woolsacks.

With the sketches in hand Lavery started work immediately on the large version which was to be his principal exhibit at the Royal Academy the following year and can now be found at the Glasgow Museums, which the Sheffield Daily Telegraph hailed as examples of ‘that most difficult branch of art, the painting of contemporary history’.

Prized for their authenticity as ‘historical documents’, Lavery’s on-the-spot sketches do not neglect the aesthetic potential of what lay before his eyes. As in the present case, collaged and disconnected vignettes are set down with remarkable spontaneity. They are neither snapshots nor newsreel. No nearby gossip nor sudden crash would distract him. Throughout his career observers commented upon his formidable concentration as the action rolled out before his eyes. He kept pace with its unfolding even in the most testing of circumstances.

Lavery frequently gave sketches like these as souvenirs to friends and sitters. In this case the study was gifted by Lavery to the sculptor George Henry Paulin ARSA (1888-1962) around 1934 when the present sketch was retrieved from the racks for Paulin in gratitude for his fine portrait of Lavery, a cast of which can be found in Glasgow Museums. Paulin’s wife, Muriel Margaret Cairns, gave it to her son-in-law as a wedding present on March 15, 1969. It passed on to the present owner by descent.

Although tempted to file away, paint over or otherwise discard his working notes, Lavery seldom did so. According to Professor Kenneth McConkey, the most eminent Lavery specialist, “When giving one to Sir Ian Hamilton for instance he told him that this was the first oil painting of the House in session, adding that it was thus, an ‘historical document’.”

Bellmans are extremely grateful to Professor Kenneth McConkey for his assistance in cataloguing this painting.