Guide to Victorian Christmas cards

Technological advances in printing made Victorian Christmas cards tiny gems of design, we explore the history of the Christmas communiqué and how they rose to such ubiquitous prominence.

Like most Christmas traditions, coloured cards with personal greetings and messages originated in Germany but were commercialised by a fortuitous combination of three factors: the penny post, an improved envelope and a more affluent public with a desire to celebrate the season of goodwill.

The First Christmas Card

The first recorded Victorian Christmas card, with a sketch and a message of greeting was commissioned by Sir Henry Cole in 1843.

Instead of writing his usual letter of Christmas greetings he decided to publish a coloured card with the message: “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you”, written on a banner and draped over a rail. The card was designed by John Calcott Horsley and originally cost a shilling, a high price for the time.

Very few of them still exist and they remain the collector’s dream find. They are marked “Published at Summerley’s Home Treasury Office, 12 Old Bond Street, London”. Perhaps because Cole was so well known – he established the Royal College of Music – his cards received undue attention and there may be others as yet unknown.

Popular Festival

It was not until the 1870s that the sending of cards became common in most families, fostered by the popularisation of the festival through songs, carols, prints and books.

Social Reform

By 1875, the middle class celebration of Christmas had emerged, with a definable concern for the poor affecting a national consciousness in Britain and America, largely through the work of Charles Dickens and other social reformers.

This theme is reflected in the cards, which show ragged children gazing through toy shop windows.

Christmas cards with their messages of goodwill, the love of God, family and friends and their persistent exposure of the state of the poor were much more a vehicle for greeting as they popularised everything that complemented Christmas, from the blazing hearth, angels, robins, waifs and crackers to the nativity itself with its hope for the world.

Victorian Christmas Shopping

Shopping had become more of a social activity in the mid 19th century with a variety of specialist dealers setting up in the small towns across Europe.

Instead of writing to London for dress fabrics and furniture, it was possible to buy all that was required for civilised living locally.

Christmas in Germany

By late November, the smallest German towns adapted their stock for the Christmas rush. William Hewitt in a book published in 1842, recalled years spent in Germany where shops displayed cards, “far more tasteful and beautiful than any Valentines that we have seen in England. Many of the cards have their centres cut out, leaving only a margin, like the frame of a picture.”

Hewitt’s description of the greetings cards common in Germany in the 1840s established the fact that the special envelopes were already available and that features which later became commonplace, such as embossed borders and cut-out centres, predated designs which were to become available in America

and Britain later.

Printing Technology

In Germany, several printers were developing colour lithography

and, by 1830, steel embossed dies were used.

Once the techniques became cheap enough, they were adapted for use in the manufacture of scraps and confectionery mottoes which were used in particular on Christmas cakes and biscuits.

Cutting dies speeded up production in the 1850s, the two processes eventually being combined.

The introduction of improved cutting machinery and, in 1863, the first machine-driven lithographic printing machine, meant that sheets of pre-cut, embossed scraps and pictures could be produced economically.

Colourful Cards

The advances led to a deluge of colour printed publications of all kinds. Gone were the laborious hand colouring and soft colours, instead every gift shop and stationer’s became a tapestry of richly glowing colours.

Mid 19th-century colour printing – whether for Christmas cards, books or prints – was still incredibly labour intensive. Sheets were passed more than 20 times through the press to achieve a richness of colour that would be totally uneconomical today.

German printing of the 1860s was commercially unsurpassed and it is this sheer quality that lures collectors into the specialist fields of Christmas cards, scraps and gift boxes.

Most of these pieces have to be assessed purely on the basis of attractiveness and quality, as they are unmarked, though most originated in the printing houses of Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden.

However, Christmas cards frequently carry the publisher’s name, as well as that of the printer, while some also reveal the name of the designer.

Penny Post

In the late 1870s, steel plates were gradually replacing the old lithographic stones and contributing to a lowering of price for all printed designs.

But all the advances of technology would have had little impact on the greetings card market if postal charges had remained high. In Britain, the fee used to be paid by the recipient and could be exorbitant, depending on the distance.

Low Cost Service

The introduction of the penny post in 1840 meant that letters could be sent anywhere in the country at a low cost, meaning that between 1840 and 1845 the number of letters sent rose from 170 million to 300 million.

Postcards, which did not require envelopes, were even cheaper and were first introduced in 1870. Like unsealed Christmas cards they could be posted for ½d, which meant that even the poorest families could afford to send them.

Royal Approval for Christmas Cards

Queen Victoria granted a royal warrant to Raphael Tuck in 1893 as the monarch sent thousands of cards to

her neighbours in Windsor and Osborne, as well as other European royalty.

However, several designers were critical of what had become an over elaborate style, including German immigrant Louis Prang of Roxbury, Boston, who started work as a lithographer in 1856.

Keeping it Simple

Prang believed cheaper printing methods should help introduce aesthetic appreciation into the lives of ordinary people – they should be simple, with no folding sections, lace or novelties.

By the 1880s, Prang’s cards were considered the pinnacle of good taste in Britain and America, partly because he used leading artists whose designs were specifically created for cards.

Regrettably, Prang ceased publication of Christmas cards in the 1890s though other firms such as Albert M Davis and Farmer Livermore and Co. continued his tradition, though perhaps not with his vision of educating public good taste.

Did you know?

Queen Mary kept albums throughout her life, a practice begun in childhood. In them she included cards from other Royal families, as well as homemade nursery pieces from her granddaughter, now Queen Elizabeth II.

Collecting Christmas Cards

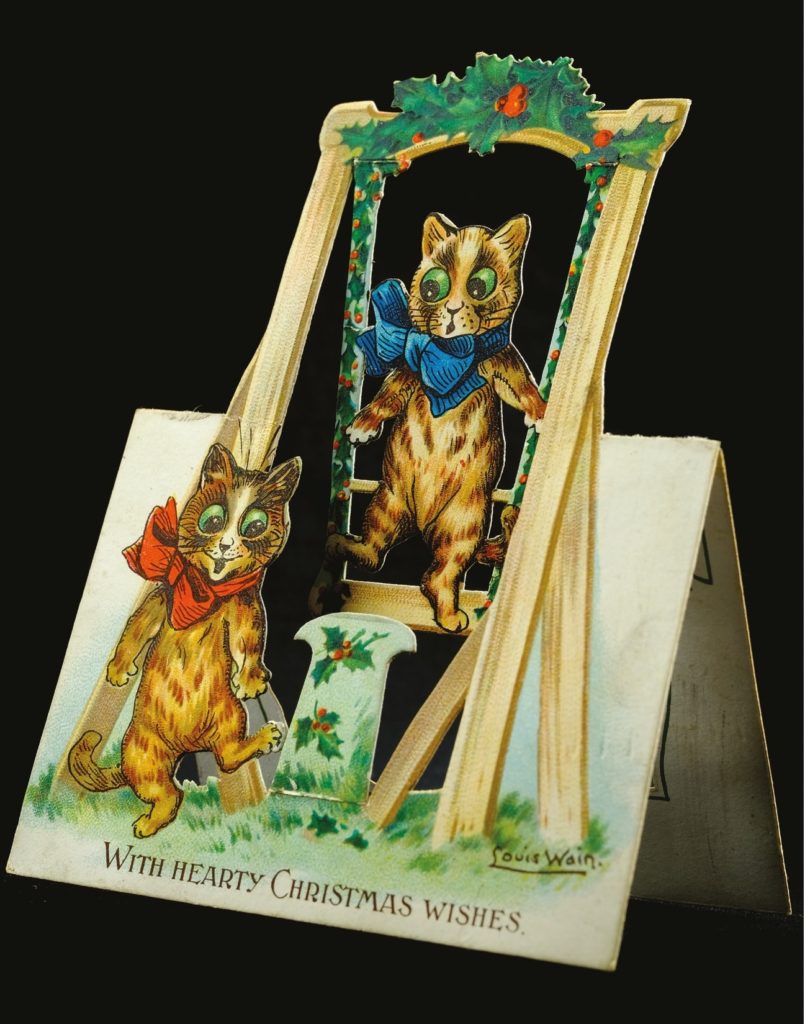

For card enthusiasts, the richest period is between 1875 and 1910, as colour printing was still of the highest quality and many experimental and novelty ideas were introduced.

Animated, mechanical transformations and various tableaux all competed with one another and are now among the most expensive purchases for antique card collectors.

Kate Greenaway, Louis Wain, the cartoonist W.G. Baxter, Mabel Lucy Attwell and Walter Crane are among the many well-known artists whose card designs are of the most interest today and attract individual specialisation.

Wondering what one would do with a scrapbook collection, say of 100 Christmas cards from 1879-1889? Who would be interested in owning this?