Metal Detecting – An Essential Guide

If you are after a cost-effective way of boosting your collection, try metal detecting. After a coin found in a field sold for a record-breaking £552,000 at Dix Noonan Webb (DNW), its antiquities expert Nigel Mills unearths some hidden gems

If you are after a cost-effective way of boosting your collection, try metal detecting. After a coin found in a field sold for a record-breaking £552,000 at Dix Noonan Webb (DNW), its antiquities expert Nigel Mills unearths some hidden gems

The Appeal of Metal Detecting

Metal detecting appeals to all ages. I know of treasures discovered by hunters aged from five to 88. Many collectors find it a great way to add to their collection, or have become collectors as a result of the finds they have made, with everything from coins, tokens, brooches, weapons, buckles, buttons and statuettes being unearthed. In America, they even collect different types of barbed wire.

Metal Detecting in America

It was in the States that metal detecting first took off in the mid 1960s when detectors capable of finding coins buried in the ground were first developed. It was not until 1971 when a new detector manufactured in the UK costing under £20 was launched that metal detecting started to become popular here.

It was called the “Prospector” and was of a very simple design using a Beat Frequency Oscillator (BFO). It was, in reality, a radio transmitter mounted on a pole which interacted with a magnetic coil enclosed in a plastic search head. It was used to locate the first Anglo Saxon hoard of silver Sceats found at Aston Rowant in the Chilterns, totalling 175 coins, deposited c. 710AD.

Development of Metal Detectors

Metal detectors quickly developed in the following years with new models using operating systems called Pulse Induction (PI) Transmitter Receiver (TR) and Induction Balance (IB). The market exploded with dozens of different manufacturers and models with prices escalating into hundreds of pounds for the top of the range.

Today’s top-of-the-range metal detectors, which cost thousands, can differentiate between ferrous and non-ferrous metals and tell you how deep the signal is, its size and shape, even give you a visual display on a screen of what is buried in the ground. In fact some users become so in tune with their machine they never waste time digging up junk.

Portable Antiquities Scheme and Metal Detecting

The archaeological fraternity became concerned this new pursuit would irrevocably damage the archaeological record and asked the government to legislate for a total ban on the use of metal detectors. This proved unpopular and metal detecting continued to flourish as more important finds were uncovered.

As not all were being declared under the ancient treasure trove laws, the Treasure Act became law in 1997, combined with the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) to ensure a comprehensive recording of important coins and artefacts found by detectorists.

Over the years, finds have added enormously to our understanding of the past. Unique coins and artefacts that would have been lost forever can now be appreciated by collectors and museums alike. The prospects for the foreseeable future look promising, who knows what spectacular treasure will be uncovered next?

The Law and Metal Detecting

Before the Treasure Act became law in 1997, the law of Treasure Trove applied to all gold and silver finds.

At a coroner’s inquest it was determined whether the recovered coin or artefact had been lost or buried for recovery. With individual coins and jewellery it was normally deemed as lost, but with groups or hoards or larger artefacts it was usually considered buried to be recovered.

If an item was lost then it was not treasure and returned to the finder; if it was deliberately buried for recovery at a later date then it was treasure and could be claimed by The Crown for purchasing by a museum.

Complications arose in the infamous case when a number of Celtic coins were found in a Romano Celtic temple in Wanborough, near Guildford in 1984. In court, the coins were classed as votive offerings to the gods so were not treasure as they were never intended to be recovered.

New Definitions of the Law

The Treasure Act, which included a code of practice, redefined ‘treasure’ as items more than 300 years old made up of two or more coins in silver or gold buried together, or 10 or more base metal coins buried together, or two or more objects buried together of pre-Roman date.

A find that falls into these categories should be reported to the local coroner within 14 days of discovery or the realisation that it may be classed as treasure. Under this criteria, neither the Allectus aureus coin, which sold for £552,000, or the Constantine solidus, on sale this month, were treasure and, therefore, could be freely sold.

At Dix Noonan Webb, we accepted the Allectus aureus only after it had been recorded by the British Museum, the time frame between discovery and the auction sale being less than three months.

The Constantine solidus was recorded on the PAS database rather than recorded by the British Museum. Auction houses require the landowner’s details so they can receive half of the proceeds of the sale – that being the usual agreement between the landowner and finder.

An item of treasure will be ‘disclaimed’ if no museum is interested in acquiring it, meaning the finder is then able to keep it or sell it with the consent of the landowner.

If a museum is interested in acquiring a treasure find then the Treasure Valuation Committee (TVC) will determine the current market value from appointed experts and offer a reward to the finder and landowner.

Finds Liaison Officers (FLO) were appointed across the country by the Department of Culture, under the Portable Antiquities Scheme, in conjunction with the Treasure Act, to record all detector finds on a voluntary basis and to accept treasure finds.

In February this year, a discussion document was released by the Department of Culture for revising the definition of treasure and the codes of practice, which interested parties were invited to respond to by April 30. The main proposed changes are that individual gold coins dating between 43AD and 1344 will be classed as treasure, as will any object found worth more than £10,000.

Mudlarking on the River

The River Thames has been a rich source of treasure finds since the dredging of the central channels in the 19th century. The Museum of London is now full of coins and artefacts found by the mudlarks over the last forty years on the foreshore.

My own searching on the river took place in the mid 1970s using just a spade and a sieve. I found coins and tokens from the Medieval and Tudor periods which were preserved in the damp airtight (anaerobic) conditions of the river silt.

We set up the Society of Thames Mudlarks in 1983 in the face of stricter controls on our activities. This group still continues today with licensed digging permits issued by the Port of London Authority.

One of the most spectacular finds was made in 1995 by a mudlark searching the foreshore on an exceptionally low tide. Using just his eyes and a trowel he found a hoard of 1,582 silver sixpences, shillings and half crowns, near Blackfriars Bridge. Dating mainly from the Commonwealth period between 1649- 60, it became known as the St Paul’s Hoard. It was not deemed treasure trove as it was considered to be an accidental loss, rather than a concealment to be recovered later.

Metal Detecting’s Golden Girl

Michelle Vall from Blackpool had just started metal detecting in 2017 when she found a hammered gold coin. It was only later that she realised it was an extremely rare

Richard III half angel dating from 1483-5. Found 11 miles from the site of Bosworth Field, the famous battle that resulted in the death of the Yorkist King Richard on the August 22 1485, the coin may have been lost by a soldier fleeing the battle.

With a face value of three shillings and four pence when it was lost, it was estimated to sell at DNW for £15,000, but went on to sell for £40,800.

Good fortune struck Michelle once again last November while visiting Loch Lomond when she uncovered a gold seal ring dating from the 17th century.

After the National Museum of Scotland ‘disclaimed’ it, Michelle was able to sell it. DNW researchers (who put its value at £10,000) identifi ed the ring’s crest as belonging to the Colman family from Brent Eleigh in Suffolk. Its style dated it to 1640-80, with its likely owner being Edward Colman, secretary to the Duchess of York, wife of the future King James II and James VII of Scotland.

The UK’s favourite Metal Detecting Hoard

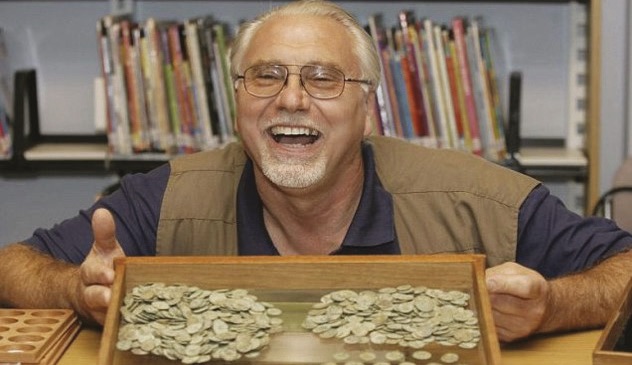

To mark the 20th anniversary of the Portable Antiquities Scheme, the UK voted for its favourite find, with the Frome Hoard – currently housed in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton – coming out on top.

The hoard was discovered in 2010 by hospital chef Dave Crisp. Housed in a large clay pot dug up near Frome, the collection – made up of 52,503 silver and copper alloy coins weighing 160kg – was the largest such hoard ever found in a single container in Britain.

The collection would have been difficult to recover after burial which led to the suggestion it was intended as a religious offering and, therefore, not treasure. The haul was buried in about 290AD.

Mudlarking on the Thames

Mudlarking on the Thames

Lara Maiklem mudlarks by sight along the foreshore of the River Thames

What stories have you unearthed in the 15 years you have been mudlarking?

What stories have you unearthed in the 15 years you have been mudlarking?

The most precious finds are those that lead me to real lives: a little airplane badge through which I discovered the story of Amy Johnson, a pioneer pilot who lost her life in the Thames Estuary; the 17th-century will of Robert Kingsland, landlord of the Noah’s Ark tavern in Bermondsey, which I discovered after finding a trade token he had issued; and a 19thcentury stoneware flagon that led to research into the history of a pub on Lower Thames Street, along with its owners and residents, that was demolished in 1920.

Have you ever submitted pieces as treasure?

Two pieces. The first was a 16th-century silver posey ring, with I LIVE IN HOPE engraved around the inside. None of the museums wanted it, so I got it back. The second was a beautifully decorated gold Tudor lace end, which was part of a mini hoard that is gradually eroding from one specific part of the foreshore. The Museum of London is collecting as much of the hoard as they can, so I donated that piece to them.

Describe the process..the best days, best weather, best places…

Mudlarking is dictated by the tides so I’m a slave to the tide tables. There are usually two low tides every 24 hours and they occur at a different time every day. Depending on where I go, there is usually about three hours either side of low tide where you can access the foreshore. I choose my spot according to my mood. If I’m feeling sociable I mudlark in central London, where there are usually other people searching. Each spot is different in character and in the finds it offers. In general there is a better variety of finds where there has been more human activity, but they also correspond to the industries that were nearby. For example there is evidence of the potteries at Vauxhall and ship building and breaking at Rotherhithe.

What has been your most heart-stopping find?

I’ve found so many wondrous things: a complete Iron Age pot, the ivory chape from a Roman auxiliary soldier’s sword sheath, a Mary I and Phillip of Spain silver shilling, a medieval ceramic toy whistle and an eighth-century Irish buckle plate. But my most heart-stopping find was a complete 16th-century child’s shoe, perfectly preserved in the anaerobic silt.

Mudlarking: Lost and Found along the River Thames by Lara Maiklem is published by Bloomsbury

This article originally appeared in Antique Collecting magazine