The history of Heal’s furniture

Heal’s furniture’s classic look of limed oak belies a store at the forefront of design fashion for more than 200 years, writes antiques dealer Holly Johnson

Heal’s of London has been a well-established name in the UK furniture market for centuries, with its classic designs finding favour with everyone from interior designers to value-conscious buyers. But the store’s longevity masks a history packed with innovation and even controversy.

Heal’s story began in 1810 when John Harris Heal, a feather dyer from the West Country, opened a shop at 33 Rathbone Place in 1810 (the business moved to its famous Tottenham Court Road location eight years later). Heal’s first incarnation was as a mattress business, selling French-style, feather-filled versions at a time when many people slept on straw palettes.

After John died in 1833 his widow renamed the business Fanny Heal & Son and with their son, also named John Harris, set about putting Heal’s on the map. The latter spotted the importance of marketing and saw the potential in advertising and, in 1837, promoted the shop on the back cover of Dickens’ novel, Bleak House – one of the first retailers to do so.

Heal’s Family Business

His grandson Ambrose Heal (1872-1959) joined the company in 1893, having completed an apprenticeship as a cabinet maker. His contribution expanded the business into a wider range of furniture, including beds, dressers, and tables. With an entrepreneurial eye finely attuned to demand, much of his output was simple oak furniture, which was fashionable with the ‘weekend cottage’ set at the turn of the century.

By the end of the 20th century, Heal’s ranked alongside Waring & Gillow and Maple & Co. as one of the best-known London furniture houses. Ambrose believed in modernity and combined a functional aestheticism with a conviction that affordable furniture produced in large-scale workshops could still be of a good quality.

He had the vision to work with the most skilled craftspeople of the day, creating furniture that was comfortable, beautiful – reflecting the ideals of the arts and crafts movement but at a more affordable price.

A lot of his designs appeared at exhibitions of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, but not everyone was a fan of his pared-back, with one shop assistant asking how they were expected to sell ‘prison furniture’?

Design Industries Association

A good friend of Ambrose Heal, Frank Pick (1878- 1941) was not only the managing director of the London Underground during the 1920s but a passionate advocate of design. In 1915, he and Ambrose founded the Design and Industries Association (DIA), to promote links between designers, manufacturers and retailers.

After WWI, the outlook of the DIA and Ambrose Heal’s friendship with Gordon Russell led to a growing interest in good modern furniture design, further consolidated by the contributions of Arthur Greenwood and J.F. Johnson to the design team.

Taking this commitment further, in 1917 Ambrose opened the Mansard Gallery on the top floor of the central London shop, with Pick providing Underground poster artwork for the first exhibition, Poster Pictures.

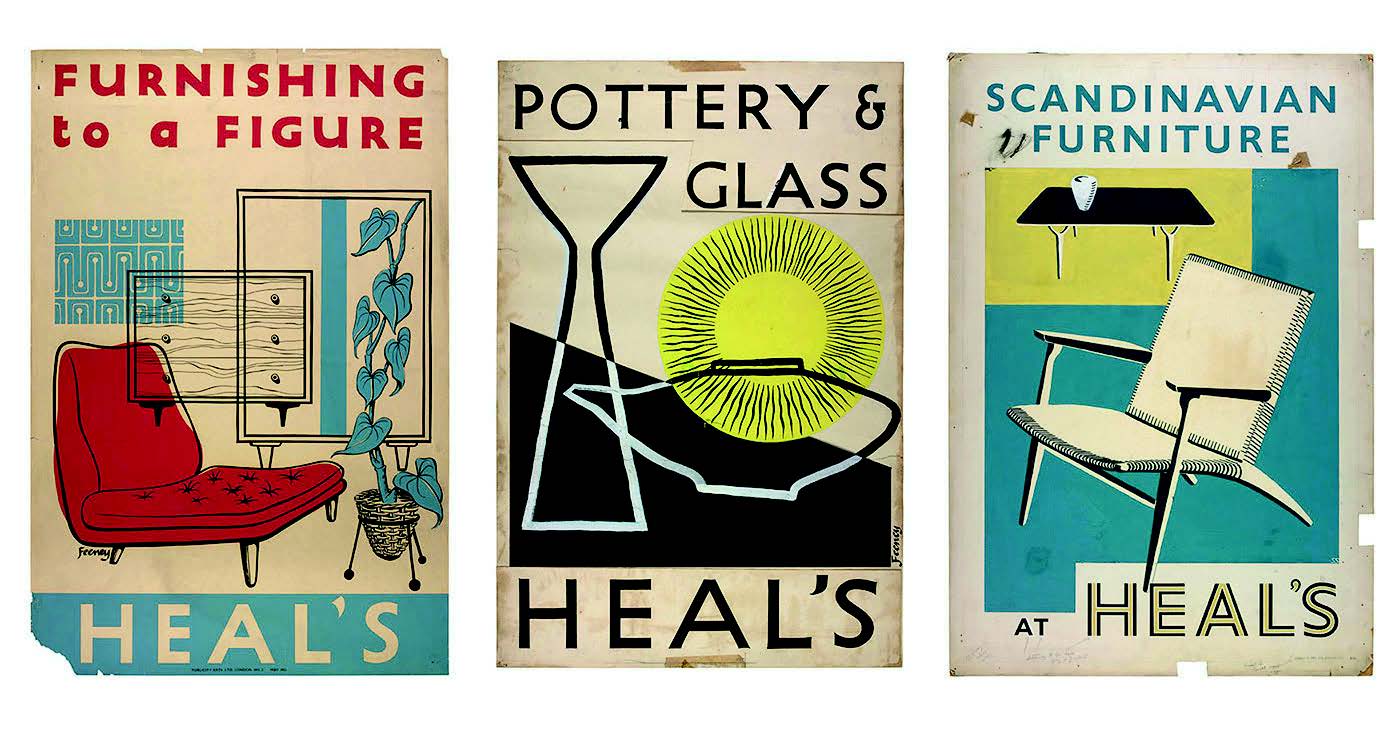

Many of those same graphic artists whose work was featured were commissioned to design posters for Heal’s newest space, including Pick’s star designer, Edward McKnight Kauffer.

Mansard Gallery

In 1916, Cecil Brewer (Ambrose Heal’s cousin) designed the iconic spiralling ‘Brewer’ staircase, leading to the gallery, further adding to the Tottenham Court Road shop as a must-visit location. The gallery was a well-known spot frequented by Bloomsbury group luminaries such as Virginia Woolf and Wyndham Lewis.

Such was his connection to the Mansard that in 1920 Lewis used the venue to host his Group X show, bringing together a number of painters and sculptors from the British Vorticist movement.

Celebrated figures such as Claud Lovat Fraser, who played an important role in graphic design and theatre set design in the early 20th century, also held exhibitions of their work at the Mansard Gallery and designed the company’s seminal posters, while its catalogues contained essays by influential art critics.

Heal’s Furniture Innovations

As the decade progressed, the Mansard Gallery increasingly served to showcase the latest developments in interior design, with some of the new styles of furniture proving more controversial than the artworks. From 1928, the Modern Tendencies series of exhibitions continued to shock commentators by bringing tubular style furniture to the high street and introducing Britain’s homeowners to the ‘moderne’ and art deco styles that were sweeping across the continent.

But the extravagance of the roaring Twenties was to be cut short by the downturn of the Thirties. Heal’s responded by launching a range of economy furniture. Ambrose invested in a nationwide promotional campaign called Heal’s Economy Furniture for 1932 and All That.

A year later, he launched the campaign, Economy with a Difference at Heal’s 1933 which took a clear step in the new, Bauhaus direction. The catalogue featured chromium-plated steel furniture, including a chair designed by Mies van der Rohe which sold for £2 9s 6d. By 1936, an exhibition entitled Contemporary Furniture by Seven Architects featured the work of another former Bauhaus professor Marcel Breuer.

WWII And Beyond

During the WWII, Heal’s factory workers turned their attention to manufacturing parachutes. Although this moved the brand in a different direction, the workforce at Heal’s learned new skills, which helped in launching Heal’s fabric arm of the business: Heal’s Fabrics. For this nascent enterprise many young and emerging designers were commissioned to produce designs, including Lucienne Day, whose Calyx design of 1951 won a prize at the 1951 Milan Triennale, and an international reputation was gained for excellence and innovation in textile design that continued to develop in the 1960s.

At the same time, furniture design still remained a strong core of the Heal’s profile with investment in Clive Latimer’s Plymet (plywood and metal) furniture and backing for his and Robin Day’s prize-winning involvement in the Low-Cost Furniture Competition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1948.

Heal’s furniture in the ‘50s

Ambrose died in 1959, having already passed control of the company to his son, Anthony, in 1953 who had already been apprenticed to the Gordon Russell furniture workshops at Broadway, in Gloucestershire, from 1927 to 1929 before entering the firm.

The company continued to expand and develop its lines often echoing the Scandinavian designers. But the looming oil crisis, alongside growing competition, began to cause problems for Heal’s and despite a number of strategic attempts to counter this, such as the Classics design show of 1981, the writing was on the wall for a philosophy that sought to promote the somewhat dated notion of good design for everyone.

Collecting Heal’s furniture

Interior designers, both in the UK and abroad, love Heal’s furniture, with furniture from the period 1900 to 1940 being especially prized.

Even during his own lifetime, Ambrose Heal’s designs evolved from the early arts and crafts influenced Fine Feather range from the late 1890s (inlaid with pewter peacock feather designs) to the more modern, linear style in the 1930s.

Heal’s aged oak and limed-oak pieces are both popular and reasonably priced, with painted furniture rarer and harder to come across. Heal’s clean lines and light woods, make it as fashionable today as it was a century ago.

The Dodie wardrobe

In 1932, Ambrose Heal designed the Dodie bedroom suite, which includes this inlaid wardrobe, for his mistress Dodie Smith, who started as a shopgirl and later penned the children’s book The Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Dodie was a key character at Heal’s during the 1920s and 1930s, where she ran the toy department, as well as being a talented buyer for the shop.

Its striking geometric zig-zag decoration is typical of the art deco style of the 1920s, which Heal’s diversified into across a range of furniture, ceramics, glass, and textiles.

The wardrobe is now part of the V&A’s furniture collection.

Holly Johnson, owner of Holly Johnson Antiques in Knutsford, Cheshire, has a range of furniture by Heal’s in stock with prices starting around £1,000, for more details visit www.hollyjohnsonantiques.com