Macabre antiques – the dark side of collecting

Whether it’s post-pandemic or just general gloom, ‘macabre’ collecting has boomed in recent years. On the eve of Halloween, Antique Collecting lifts the lid on the dark side of antiques and artefacts

Whether it’s post-pandemic or just general gloom, ‘macabre’ collecting has boomed in recent years. On the eve of Halloween, Antique Collecting lifts the lid on the dark side of antiques and artefacts

When the saleroom doors open on Sworders’ annual Out of the Ordinary sale there’s no saying who will come through them. Recent bidders have included an entire witches coven (after a mummified cat) and a stag party (keen to purchase a vampire slaying kit).

One thing they have in common is they both reflect the growing upward trend in ‘dark’ collecting. Mark Wilkinson, who has curated the sale for the past five years, said: “If there is one area what has seen real growth it is witchcraft.” Several factors are at play, not least the recent rise in the occult. Partly inspired by social media, including sites such as witchtok, and the boom in TV shows, contemporary paganism is on the up.

Wilkinson continued: “We are also based in Essex which has a huge tradition of witchcraft dating back to the Matthew Hopkins the 17th-century Witchfinder General responsible for putting up to 100 alleged witches to death.” This month sees an ongoing exhibition on witchcraft in Colchester, the county town of Essex where its castle was a key landmark in the Essex witch trials. In that county alone 1,000 people were accused of witchcraft from the 1500s to 1800s, with accusations ranging from using animal familiars to kill neighbours to meeting in secret and reading from mysterious books.

Dark side of collecting

James Gooch, from the Bedfordshire-based dealer Doe and Hope, said: “Demand for the macabre may have become more ‘normal’ with the advent of social media and the acceptance of being more different. The idea that it is cool now, I guess, helps, but, essentially, the true collectors are not part of a fad it’s an ingrained curiosity for the darker side.”

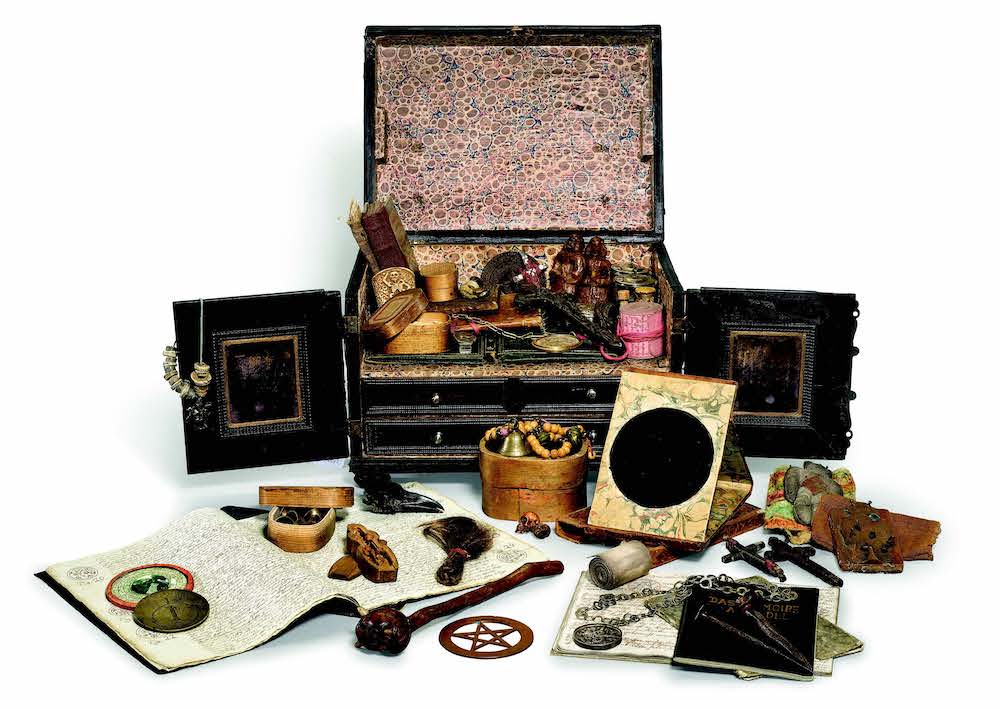

And the true collector is prepared to pay what it takes to secure the best and most authentic pieces. Last May at Sotheby’s when the hammer fell on lot 170, the buyer became the owner of a casket containing, among its talismans and amulets, a preserved crow’s head, a length of plaited hair and a collection of animal teeth. Expected to make £4,000-£6,000 the wooden box, described as ‘the property of a German gentleman’, fetched £20,000.

Witch hunt

While vampire slaying kits embody the theatrical, with other areas of ‘dark’ collecting, authenticity is everything. When a court record of the trial of two Suff olk witches in 1664, which had been expected to make £600-£900, went under the hammer in 2019 it sold for £5,400.

Titled A tryal of witches at the Assizes held at Bury St Edmunds on the tenth day of March, 1664. Before Sir Matthew Hale. Taken by a person then attending court it was a first-hand account of the trial of two elderly widows Rose Cullendar and Amy Duny who faced 13 charges of the bewitching of several young children between the ages of a few months to 18 years old.

In March this year Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon issued an apology to the estimated 4,000 people accused of witchcraft between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Blood suckers

Belief in vampires, an undead creature said to need human blood to survive, goes back hundreds of years and persists in some parts of the world today. They are enshrined in European folklore. The publication of John Polidori’s The Vampyre in 1819 had a major impact and that was followed by Bram Stoker’s 1897 classic, Dracula.

A month after the Sotheby’s sale, a vampire-slaying kit once owned by Lord Hailey, a British peer and former administrator of British India, expected to make £2,000- £3,000 at the Derbyshire auctioneers Hansons, sold for £13,000 after sparking an international bidding war. Charles Hanson said: “Bids came in from all over the world including France, America and Canada. Objects like this fascinate collectors and this one had a particularly interesting provenance.” Items in the late 19th-century kit included a matching pair of pistols, brass powder flask, holy water, a copy of The Bible, wooden mallet, stake, brass candlesticks and rosary beads.

Evil eye

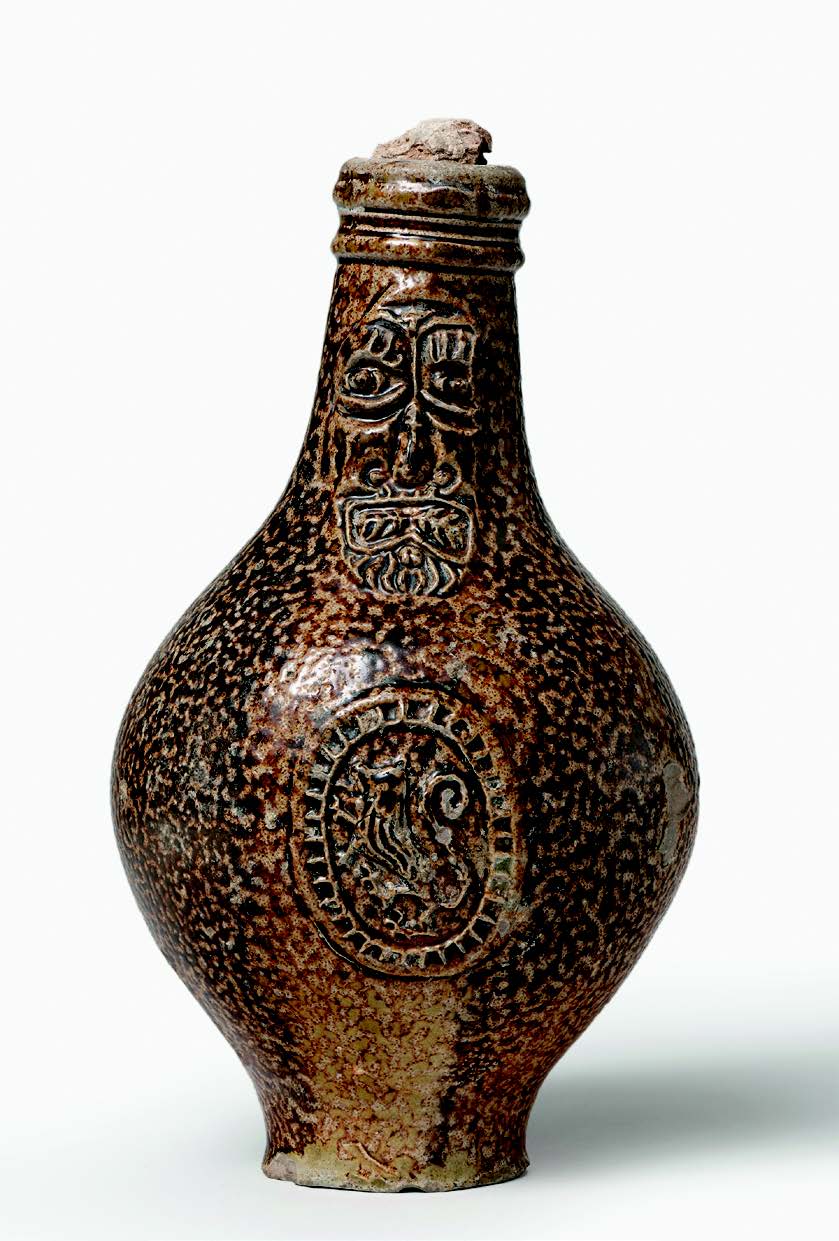

If you really wanted to ward off the evil eye there were (and are) a number of tools at your disposal from stoneware “witches’” bottles (which were filled with a bizarre assortment of iron nails, lead shot, bundles of hair, and a heart-shaped piece of felt pierced with pins) to mirrors. So-called “witches’ bottles” (their actual purpose is disputed) often crop up in urban archaeological digs.

Their contents were described in The Astrological Practice of Physick, published in 1671, which offered a how-to guide for preparing a bottle to protect its owner from witchcraft.

According to the folklorist Ralph Merrifield: “The supposed victim of witchcraft would put some of his urine in a bottle with pins or needles, and bury it, believing that this would inflict acute pain on the witch, who would be unable to pass water until the spell had been removed.”

German-made stoneware Bellarmine jugs, used as 17th-century drinking vessels, were often used as witches bottles. Their human-like shape and featuring a frightening face were seen as good ways to repel witches. It was commonly believed that a witch bottle could capture an evil spirit which would be impaled by the nails and pins and drowned by the urine. Another theory is that the bulbous shape of the Bellarmine jug represented the witch’s bladder.

Cat’s tale

As stories of witchcraft raged from the 16th to 18th centuries so too did ways to combat its malevolence. Thousands of concealed objects have been found in homes around the country, the result of rituals conducted by people known as “cunning-folk”, to foil witches. Some remedies were simple: horseshoes placed above doors, and iron thought to repel witches.

The chimney was for centuries believed to be a gateway for bad spirits and therefore one of the greatest threats to the home. It became common custom in Britain to place the dried or desiccated body of a cat inside the walls of a newly-built home to ward off witches, evil or as a good luck charm. Although some accounts claim the cats were walled-in alive, examination of recovered specimens indicates post-mortem concealment in most cases.

Mirror mirror

Equally effective in the battle against evil are sorcerers’ mirrors, witches’ balls and scrying mirrors. The former were commonly hung in the home, where the distorted image would ward off evil spirits. The use of a scrying mirror – some of which are entirely black – is somewhat different. They were more likely used for divination, with the word “scrying” meaning “to make out dimly” in Old English. Scrying involved gazing into the surface to see images or visions, a practice popular among early 20th-century English witches. Earlier this year a Victorian scrying mirror smashed its low pre-sale estimate of £200 to sell for £2,4000 at Sworders.

The most famous owner of a scrying mirror was the alchemist Dr John Dee, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, who used a black obsidian mirror and a crystal ball to see visions of the future. The scrying mirror is today on display in the British Museum.

Decorative appeal

As well as being popular among dedicated collectors of the macabre, unusual pieces are highly sought after by interior designers as coversation-provoking one-offs. Wilkinson continued: “30 years ago if you decorated a room it would have been purely in the Regency or, say, art deco style. Now there is a total mix of design styles. Added to which, collecting tastes are becoming ‘darker’. The very wealthy are attracted to these type of sales. Let’s face it, if you have everything, why wouldn’t you want a fake mermaid in your bathroom?”

While the public’s interest in taxidermy peaked five years ago, today only the best pieces appeal to collectors. Doe and Hope’s James Gooch, who collects Jack the Ripper-related items and pieces connected to lunatic asylums, said: “You can add these pieces to any interior in my opinion. Life is all about balance and this applies to the amount of macabre you can add to a room without it tipping over into a goth interior.”

Wilkinson continued: “Sorcerors’ mirrors might not be used for divination today but imagine how great they would look as a group on a wall.”

Wicked Spirits? Witchcraft + Magic, produced in partnership with the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle, continues at Colchester Castle until January. Sworders’ annual Out of the Ordinary sale takes place every February.

Did you know?

Medium Helen Duncan was the last person to be conviced of witchcraft after the ‘ectoplasm’ she conjured turned out to be regurgitated cheesecloth. She received a six-month sentence in 1944 under the Witchcraft Act of 1735.

A New Broom

Publishing innovations of the 16th and 17th century witnessed an explosion of printed material, sparking an information – or misinformation – revolution. The revolution coincided with, and helped create, what has been termed “the European witch craze”: a moral panic and collective psychosis that spread through Europe and Scandinavia.

Cheap print was the medium of the masses, and the crude woodcuts were the visual language of early modern England. The folkloric image of the crone was established and repeated in similar pamphlets over the next century. These witches were usually bitter old women who lived on their own and kept cats or other animals as pets. Torture was recommended for extracting confessions, death was now the penalty, even for a “good” witch.

Cabinet of curiosities

Today’s interest in the macabre and downright unusual is, in part, due to the resurgence of interest in the cabinet of curiosities. First created in Renaissance Europe, these collectors’ rooms were microcosms of the universe. Also known also as wunderkammer or kunstkammer, they didn’t have to be scientifically accurate. Some contained stitched-together artefacts from diverse sources which created fantastic creatures closer to art than to nature. Most of the great museums of the world grew out of such collections. Rudolf II’s kunstkammer is at the heart of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum while Sir Hans Sloane’s collection became the nucleus of the British Museum. The 19th-century scientifically-arranged museum rang the death knell on cabinets of curiosity as “curio” became a derogatory term.