Ancient Egypt’s influence on western design – the essential guide

Ben Hinson, curator of an ongoing exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre, Visions of Ancient Egypt, considers the legacy of ‘Tutmania’ on centuries of art and design

Ben Hinson, curator of an ongoing exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre, Visions of Ancient Egypt, considers the legacy of ‘Tutmania’ on centuries of art and design

This year’s centenary of Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 is shining a light on Ancient Egypt not seen since the British Museum’s display of 50 objects from the tomb of the Boy King attracted 1.7m visitors in 1972.

A major exhibition on Ancient Egypt opens at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, with further exhibitions at the British Museum, Oxford and Bradford. Whether they will be enough to spark the second wave of ‘Tutmania’ as seen after the 1972 exhibition remains to be seen, but one thing is sure, it will reignite collectors fascination with Ancient Egypt.

Egypt – or at least an idea of Egypt – has inspired Western artists and designers for centuries. It survived most prominently through Biblical stories; almost everyone in the Western world had heard of Egypt and its ancient rulers, even if the Bible associated them with despotism.

Artistic interest in Egypt re-emerged in medieval Italy, and peaked in the Renaissance. At this time, few people had travelled to Egypt – really only religious pilgrims – and so most encountered Egypt through monuments and objects seen in Rome, that had been looted in ancient times. This Egyptian material became part of the larger rediscovery of Classical antiquity, and so Egypt was seen through a Roman lens. Most commonly, artworks made by the Romans but in an ‘Egyptianising’ style were mistaken as genuine Egyptian objects.

Secret wisdom

Because hieroglyphs had not yet been deciphered, they were mistakenly believed to conceal secret wisdom. Many artists were inspired by this idea, even coming up with a new system of ‘neo-hieroglyphs’ where symbols stood for concepts and ideas.

The works of Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) frequently include such symbols, often hidden cryptically. Furthermore, Egypt was seen as the land where concepts like law and justice originated, and so religious elites co-opted Egyptian imagery as part of their identity, to legitimise their own rule.

Some, such as Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo de Borgia) even went so far as to craft imaginary family genealogies stretching back to Egypt itself.

Imperial ambitions

In early 19th-century France and Britain, there was a wave of Egyptian-inspired art and design, particularly in elite and imperial contexts.

Egyptian art was popular because both countries wanted to occupy Egypt, and so adopting its visual culture was a proxy for physically controlling it. In Britain, for example, crocodiles became very popular in art following the Battle of the Nile, where Nelson defeated Napoleon’s forces in Egypt. Here, crocodiles represented not just Egypt, but also referenced imperial victory.

Into the Victorian era, when Egypt became a British colony in all but name, the presence of Egyptian motifs in art and popular culture exploded even further. The use of Egypt in European art and design has often carried political or imperial undertones.

Despite the trajectory of European ‘rediscovery’ of Egypt, it was never lost to the Arabic-speaking world in the same way. Arabic geographers, scientists and historians had been travelling to Egypt for centuries before Europeans started to do so, engaging with its monuments and remains.

Early adopters

At the same time, Josiah Wedgwood was pioneering an ‘Egyptian’ style in Britain, in Italy, the printmaker and antiquarian Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) looked to a range of ancient sources, including Egyptian, Etruscan and Roman, reinventing them for modern living. Piranesi was again inspired by the objects viewable in Rome. In both cases, their imagined designs had little to do with ancient Egypt in an academic sense, but introduced Egyptian motifs as a decorative style.

At this time, historians believed European art evolved from ancient Greece and Rome. Egypt was not seen as part of the same story, but rather a less advanced forerunner.

Therefore, designers like Wedgwood and Piranesi, who promoted an Egyptian style, consciously did so as a foil to this Classical narrative and, as a result, their designs were not always appreciated. It was only when hieroglyphs were deciphered, and Egypt’s history became ‘readable’, that the place of Egypt in Western art history was re-considered.

Egypt was now placed not just at the beginning, but as the origin of Greek and Roman art itself. Egyptian art was much more ‘acceptable’ and found greater mainstream approval. Crucially, this also reinforced a belief that ancient Egypt was part of Western history, not African.

Military campaigns

In the early 19th century, the French invasion of Egypt was a military disaster, but a scholarly success – grand publications like the Description de l’Égypte and Voyage dans la basse et la haute Égypte were hugely influential among taste makers.

Across the Channel, furniture designer Thomas Hope (1769-1831) was among those making Egyptianising interiors fashionable.

Orientalist trend

In the later 19th century, increasing archaeological discoveries influenced a whole new generation of artists and designers, who looked to objects in museum collections for inspiration.

Orientalist artists such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edwin Long and Edward Poynter painted huge genre paintings of scenes from Egyptian life, which were furnished with objects copied directly from museums.

Similarly, furniture designers also closely studied Egyptian artefacts to inform their own work. One inlaid stool in the British Museum was particularly influential. A chair, designed by the pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt, faithfully copied its shape and details. The department store Liberty & Co. advertised a ‘Thebes stool’ based on the same artefact, available in a range of sizes and materials. In terms of jewellery, the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1867 was a crucial moment when jewellers looked to ancient Egyptian motifs. The beautiful jewellery from the tomb of Queen Aahotep was displayed at the exhibition, and captured the public’s imagination.

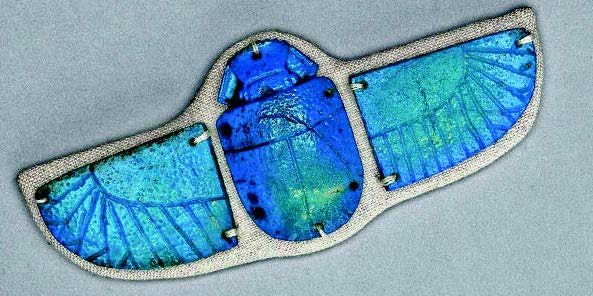

Jewellers such as Mellerio dits Meller, Gustave Baugrand and Émile Philippe all participated in this trend, crafting spectacular pharaonic-inspired objects. By the end of the 19th century, art nouveau designers like René Lalique had re-popularised Egyptianising designs, looking, in particular, to the scarab motif.

20th-century legacy

At the same time as Tutankhamun’s treasures saturated popular culture in Europe and North America, African-American artists of the Harlem Renaissance wished to re-position Egypt as part of their heritage, to inspire pride in African-American culture at a time when, despite emancipation, many remained oppressed, disenfranchised and segregated. Artists like Meta Warwick Fuller and Aaron Douglas drew upon ancient Egyptian visual culture to create powerful representations of the modern African American experience.

Similarly, in Egypt itself, a generation of artists who had trained in Europe also turned to Pharaonic imagery, to make their own statements about Egyptian identity and nationalism.

The unearthing of the king by a British archaeologist took on symbolic significance, as it coincided with the rise of nationalism and demands for independence from Britain. It spurred a political and artistic movement known as Pharaonism, which revived Pharaonic imagery to make direct links between ancient and modern Egypt.

Sculptors like Mahmoud Mokhtar and, later, Mahmoud Moussa, and painters like Mahmoud Said, modernists who had trained in Europe, turned to this theme in their works. These artists are little known and collected in the West, and their legacy therefore underappreciated outside of Egypt today.

Wedgwood’s Egyptian Designs

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) was one of the earliest designers to pioneer an ‘Egyptian’ style in Britain, from the late 1700s onwards. He never visited Egypt relying on books – many of which were unreliable – as his main source of material.

His canopic jars (originally made in the Egyptian city of Canopus and used to preserve the viscera of the deceased) were based on Plate CXXXII of Bernard de Montfaucon’s L’Antiquité Expliquée published in Paris in 1719. Another possible was Michel-Ange de la Chausse’s Museum Romanian, published in Rome in 1746.

Black basalt

Wedgwood basalt was a black vitrified stoneware made from refined ball clay, ironstone slag and ochre, which, when mixed together with manganese, coloured the clay to a dense black. It was developed in the late 1760s and considered of higher quality than previous black stonewares made in Staffordshire known as “Egyptian black”.

The second volume of Wedgwood’s 1777 Catalogue of Cameos describes it as “Having the Appearance of antique Bronze, and so nearly agreeing in Properties with the Basaltes of the Egyptians, no Substance can be better than this for Busts, Sphinxes, small Statues &c. and it seems to us to be of great Consequence to preserve as many fine Works of Antiquity and of the present Age as we can, in this Composition.”

Long production

Wedgwood’s Egyptian designs fall into three distinct phases: those produced during the Wedgwood and Bentley partnership from 1768-1780; those of Josiah Wedgwood II in the early 19th century incorporating hieroglyphic designs; and the later re-issues and revivals.

The Wedgwood/Bentley Egyptian wares include sphinxes, Egyptian deities, a Cleopatra, Canopic jars, candle-sticks, and cameos made in black basalt or blue-and-white jasperware.

The second group was mainly made up of pieces decorated with bogus hieroglyphs and various Egyptian motifs in black basalt on a rossoantico ground. An 1805 ink-stand made of black basalt with red decorations, and a rosso antico teapot, cover and stand is on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Ancient Egypt and art deco

Although the emergence of art deco was due to interest in a range of non-Western cultures, sparked by the flow of objects arriving in Paris from her colonies, France had had a long engagement with Egypt, and its visual culture was easily assimilated into the new language of art deco. The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 of course accelerated the saturation of Egypt into popular culture even further.

French fashion houses took the lead in promoting the ‘Egyptian style’ among the fashionable and wealthy, through leading designers such as Paul Poiret.

Expensive beaded and embroidered garments were followed by more affordable printed fabrics, with British companies such as Steiner & Co. making both textile and furnishing fabrics indebted to Egyptian motifs.

In jewellery, again French makers such as Van Cleef and Arpels and Cartier produced Egyptian-inspired pieces. The lattéer in particular married a love of Egyptian style with the passion for acquiring Egyptian antiquities, by incorporating real artefacts into new objects.

Benjamin Hinson is one of the curators of Visions of Ancient Egypt which opens at the Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia, Norwich. It is on from September 3, until January 1, 2023, with more information available at www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk