Guide to Ince and Mayhew furniture

The partnership of William Ince (1737–1804) and John Mayhew (1736–1811) ran from 1758 to 1804 and was one of the most enduring and well-connected collaborations in Georgian London’s tight-knit cabinetmaking community. The partners’ clientele was probably larger, and their work was arguably more influential over a longer period, than most other leading metropolitan makers – perhaps even than that of their older contemporary, the celebrated maker Thomas Chippendale.

The partnership of William Ince (1737–1804) and John Mayhew (1736–1811) ran from 1758 to 1804 and was one of the most enduring and well-connected collaborations in Georgian London’s tight-knit cabinetmaking community. The partners’ clientele was probably larger, and their work was arguably more influential over a longer period, than most other leading metropolitan makers – perhaps even than that of their older contemporary, the celebrated maker Thomas Chippendale.

Despite their considerable output and an impressive tally of clients, including some 97 commissions, much of their work remained unidentified – until recent times. But a new book, 40 years in the making, by Hugh Roberts and Christie’s International deputy chairman, Charles Cator, has trawled private family archives, county record offices and bank archives to reveal compelling new evidence about the business and its influence within cabinetmaking circles.

Vanguard of fashion

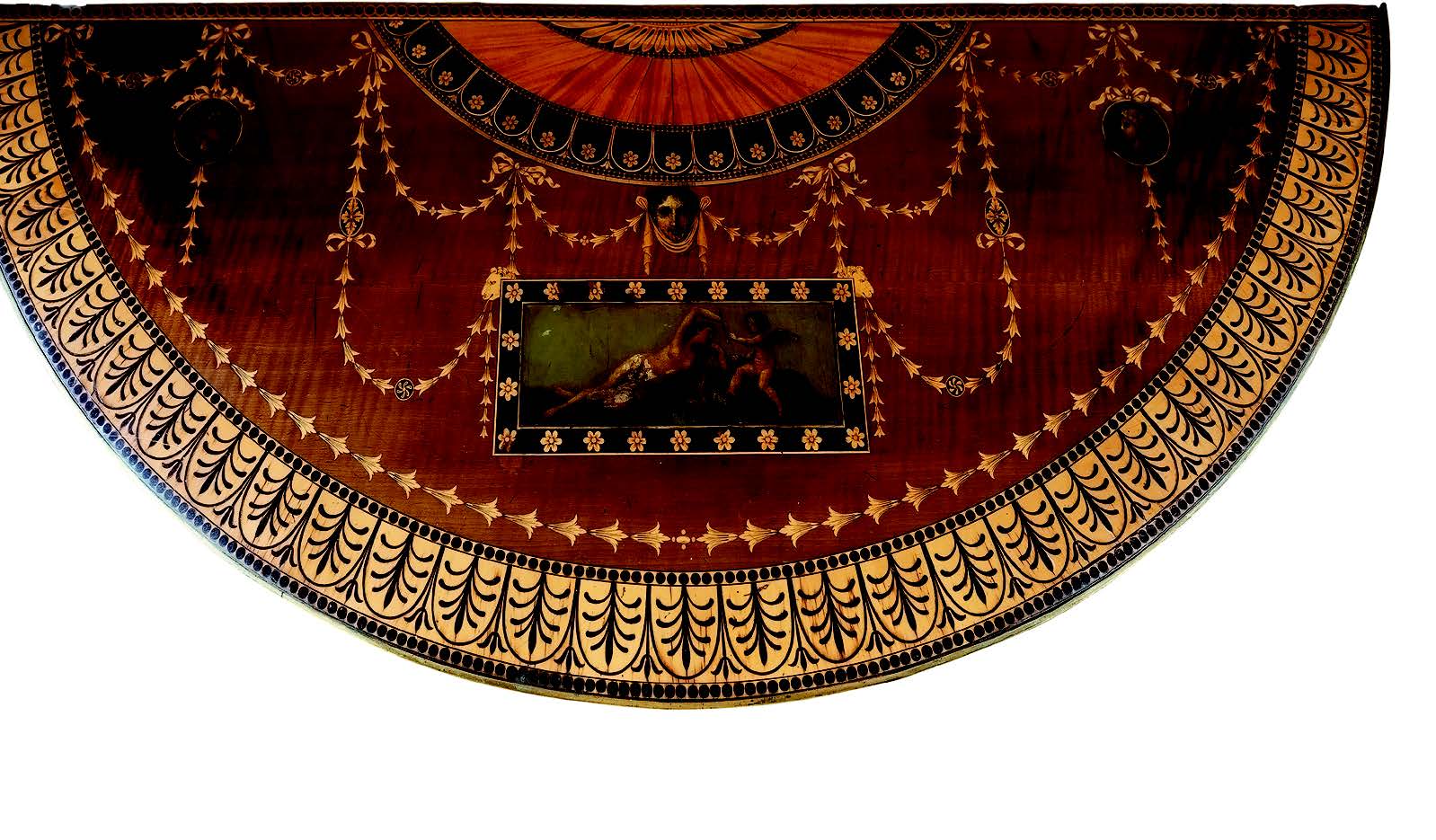

In some key areas, namely marquetry decoration and popularising painted furniture, Ince and Mayhew led fashion more than many of their rivals.

Both men were raised in the heart of the capital’s artisan quarters and the centre of the cabinetmaking trade, Soho and Covent Garden, and were therefore extremely well placed to exploit their trade connections.

Mayhew was originally apprenticed to William Bradshaw, the upholsterer, of Soho Square, and Ince apprenticed to John West of Covent Garden from 1752 until West’s death in 1758.

Once partnered, the pair had workshops in Broad Street, Soho, followed by a space on Marshall Street, Carnaby Market. Initially describing themselves as ‘cabinet makers, carvers and upholders,’ this was variously amended over the term of the partnership to include such terms as ‘dealers in plate glass,’ with the categories of ‘cabinet maker’ and ‘upholsterer,’ however, remaining constant.

They worked closely with Robert Adam, most notably for Sir John Griffin at Audley End in 1767, for the Duchess of Northumberland in 1771, for the Earl of Kerry in 1771 and, most importantly for the Duchess of Manchester in 1775, creating the Kimbolton Cabinet.

Modern offering

With carvers, gilders, painters, upholsterers, brass founders and metalworkers, as well as suppliers of timber, mirror glass, fabrics, tapestry and upholstery materials, all within the partners’ reach, their comprehensive service foreshadowed that offered by later 19th-century furnishers and more than equalled that of modern designers.

Despite their obvious capabilities, until recent times little more than the partners’ names and their reputation as authors of a pattern book published in 1762 – The Universal System of Houshold Furniture – had survived. Similarly, little of the firm’s very considerable output, or its impressive tally of clients and commissions, had been identified, let alone studied.

There is, regrettably, no surviving equivalent in Ince and Mayhew’s oeuvre to Chippendale’s spectacularly rich, largely intact and well-documented schemes of furnishing and decoration at Dumfries House, Harewood House, Nostell Priory and Newby Hall.

The Universal System

Ince’s design skills were put to the test early in the firm’s existence when the partners decided on the ambitious publication of a substantial new design book. It was to be a conscious imitation of Chippendale’s highly successful 1754 publication, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, to which Ince was a subscriber as an apprentice, and which was reissued with minor variations in 1755.

The plan for Ince and Mayhew’s publication, announced on July 10, 1759, promised ‘near Three Hundred Designs’, on 160 large folio plates, to be issued in 40 weekly instalments of four plates each, at one shilling for each cahier; and at the conclusion there would be 40 pages of descriptive letterpress.

An advertisement 14 days later promised ‘upwards of 450 designs’, and in a provocatively worded announcement aimed at Chippendale and the Director, they stated on December 25 that their publication would be ‘so universally esteemed for its being the Gentleman’s best Director of Choice, and the Workman’s in the Execution of any Design’.

Chippendale competition

In fact the publication plan was heavily curtailed after the issue of cahiers 19–21, advertised in September 1760. The 89 plates published by then (all but one signed by Chippendale’s principal engraver, Matthew Darly), together with six more anonymous sheets of a utilitarian and less sophisticated character, were reissued in bound folio form as The Universal System of Houshold Furniture.

The reason for the abandonment of the original plan was no doubt in part financial: such undertakings were costly and risky, requiring more time and money than the fledgling partnership could reasonably afford.

However, the main cause must have been news – first advertised by Chippendale on August 18, 1759 – of the publication (on October 6, 1759) of the first four plates of what was to become the third edition of the Director.

Like Ince and Mayhew’s work, and no doubt inspired by it, Chippendale’s plates were to be issued weekly. By March 1760, he had produced 100 plates and it must have been clear to Ince and Mayhew that the competition, reinforced by a vigorous advertising campaign, was overwhelming.

Furthermore, conscious of the considerable significance to his fashion-conscious clientele, for the first time Chippendale included a number of neoclassical motifs, while Ince and Mayhew’s designs remained firmly anchored in the elaborate conventions of the high rococo.

New designs

The dependence of The Universal System on both the idea and the content of the Director has never been in doubt. However, the inclusion of a small number of furniture types not included in Chippendale’s publication, notably tripod or ‘claw’ tables and card tables, goes some way towards relieving the charge of straight plagiarism. As does the accomplished and (within reason) fresh interpretation of certain furniture types popularised by Chippendale – for example candle-stands and beds.

Perhaps the most idiosyncratic and individual feature of the partners’ designs is the repeated use of a variety of symmetrically-formed half-Gothic, half-Chinoiserie lattice or fretwork panels and the design for two ‘Ecoinears’ (corner cabinets).

The relative lack of success of The Universal System as a design manual (there were no further editions) and the paucity of documented furniture in the style of the publication (despite the claims that a number of engraved pieces had been executed) are no doubt connected. By 1763, the rococo style had passed its zenith – as Chippendale had certainly already realised – and taste in furniture (as in architecture) had begun to shift decisively from rococo exuberance towards neoclassical sobriety.

Commanding commodes

This variation of style was most visibly expressed in the production of commodes. This was a furniture type which, to judge from the number of documented or attributed examples that survive (or are mentioned in surviving bills), came to dominate Ince and Mayhew’s output. The firm’s most original manifestation being the semi-circular or semi-elliptical commode, a design undoubtedly due to the neoclassical architect Robert Adam.

Of this type, the earliest known, best documented and certainly most influential example, spawning many progeny in the firm’s output, was made for Derby House in 1775. Closely allied to this form, and equally responsive to neoclassical decoration, was the semicircular, semielliptical or serpentine marquetry and giltwood pier table – again something of a speciality of the partners – with the top laid out and decorated in precisely the same way as for the top of a commode.

Adam may also have inspired another form in which the firm specialised, the rectilinear box-shaped commode, often made with side-opening doors and designed principally as a vehicle for the display of marquetry.

French influence

Alongside their ready adoption of neoclassical forms and decoration, a restrained influence, owing much to French precedent, persisted in the firm’s output throughout the 1770s and well into the 1780s. This can best be seen in the continued production of the ‘Louis XV’ type of commode, with shaped apron and bombé front (a format popularised by John Linnell and Pierre Langlois in the first half of the 1760s). Chippendale, by contrast, seems to have abandoned this style entirely around 1770 in favour of a more thoroughgoing neoclassicism.

A variation on this theme in the same period appears in commodes of basically rectangular form, but with serpentine fronts, fitted either with cupboard doors or drawers framed by bold fluted angles. The French influence was also expressed in two other furniture types, both a speciality of the firm. Corner cupboards (‘ecoinears’) were a staple of French furniture production through most of the 18th century, but uncommon in English furniture. They appear with considerable frequency in the firm’s output, generally with a commode en suite. Upright cabinets, a great number of which were made by the partners, also derive from French precedent and function as secretaires, cupboards or chests of drawers.

Firm’s dissolution

On December 31, 1799, some 19 years after the intended expiry of the partners’ original articles of partnership, a new agreement was signed detailing the dissolution of the partnership. The reasons were no doubt both personal and financial: the partners were in their sixties, with families requiring support, and the run of good fortune which had kept the partnership solvent had shown signs of coming to an end as the impact of the wars with France took hold.

Identification of the firm’s 97 documented commissions has been hampered by the fact that time and chance has dealt heavy blows to many of the families, collections and houses at the heart of them. More research can only highlight the partnership’s proper position in the pantheon of great 18th-century cabinetmakers.

Marquetry Skill

With case furniture, one common link is the partners’ use of marquetry, including large-scale motifs from antiquity, copied from engravings (habitually urns, vases or tripods), typically simply coloured and boldly inlaid on a contrasting ground. Secondly, extensive and delicate shading and surface engraving of the inlay, heightened with black, red or white mastic to mimic printed engravings. Another feature is the subtle inlaying (usually of foliage designs), differentiated from the ground wood only by the contrast of the natural

colour and figure of the inlay.

Other characteristics include the sympathetic modernisation and re-use of good examples of earlier marquetry, notably late 17th-century floral panels – an antiquarian trait that sets them significantly apart from almost all of their contemporaries and rivals, notably Chippendale, all constituting their original contribution to English furniture decoration.

Carving skills

As well as marquetry, the firm’s ability to produce carving of the highest quality – whether for pier glasses, tables, picture frames, case or seat furniture – remained central to their output.

This continued even after the rococo style, with its overwhelming emphasis on fluent naturalistic carving, had fallen out of fashion. Ince (whose designing skills had been nurtured in the rococo) undoubtedly played the leading part in ensuring these skills continued into the neoclassical.

Partly in response to the new neoclassical aesthetic adopted by the fashionable world, painted decoration (‘japanned’, as it is described in most of the bills) played an increasingly mportant part in the firm’s production from the late 1760s, as it did with Chippendale and other leading makers.

While there was no invariable rule, it seems that painted finishes tended to be supplied for the more intimate rooms in a house, especially bedrooms, where painted rather than gilded furniture – chairs and beds in particular – were found. In general, painted furniture was probably more frequently seen in the country than in London.

If a choice had to be made, cost as much as aesthetics no doubt dictated that gilding would be reserved for the principal reception room of a house (whether in London or the country), while less expensive painted finishes would be chosen for other rooms.

Taken from Industry and Ingenuity: The Partnership of William Ince and John Mayhew by Hugh Roberts and Charles Cator published by Philip Wilson Publishers, £75.

Taken from Industry and Ingenuity: The Partnership of William Ince and John Mayhew by Hugh Roberts and Charles Cator published by Philip Wilson Publishers, £75.