A quick guide to Dogs in Art

A new exhibition shines a light on how man’s best friend has been portrayed over the centuries. Antique Collecting takes a look and bones up on starting a collection

A new exhibition shines a light on how man’s best friend has been portrayed over the centuries. Antique Collecting takes a look and bones up on starting a collection

It was from the Renaissance onwards that it became fashionable for wealthy sitters to be represented with their dogs in a manner which allowed the artist to reveal more about the sitter. Dogs were seen as symbols of loyalty: Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata (1531) stated confidently that dogs mean fidelity, while Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593) suggested “the dog is the most faithful animal in the world, and beloved by men.”

Dogs were also synonymous with high social status and wealth, for only such people could lavish attention of this sort on their dogs.

Dogs appear in works by Van Dyck, as well as Titian, Velázquez and Rubens, their addition lent an informality to the scene while allowing the artist to introduce an element of wit as well as challenging their naturalistic skills in a different way.

The breed most associated with Titian’s paintings is the papillon (named after its butterfly-like ears), also known as a “Titian spaniel”. The diminutive size of such toy dogs was perfect for images of children, while Velázquez tended to prefer mighty Spanish mastiffs in his hunting portraits of the Spanish royal family.

Hunting hounds

It was in the 17th century that dog portraiture acquired such stature that the representation of the dog alone was enough to indicate the nobility of the family that owned it. Dog breeding was an obsession among the well-established landowning families and, by the second half of the 18th century in England, dog portraiture was flourishing. Landowners and aristocrats were affluent enough to commission stand-alone portraits of their favourite dogs.

The hunting set enjoyed a special relationship with their dogs, distinct from that of their French counterparts – perhaps due to different approaches to the sport. Shooting in Britain was a more solitary pursuit, carried out by a squire and his keeper with a few dogs. The performance of the individual dog, rather than the pack, became more important in determining the success of the hunt.

Hunting dogs were treated as prized possessions and objects of interest in themselves, becoming a status symbol of landowning and the landed English aristocracy.

Thomas Gainsborough’s Dogs

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) had a countryman’s love of dogs and included them in numerous portraits and landscape paintings. He also painted a few works where dogs were the central subjects. While most individual canine portraits were produced for their owners, he also painted his favourite dogs Tristram and Fox (named after the hero of Laurence Sterne’s novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–67) and the Whig politician Charles James Fox).

Gainsborough’s affectionate portrayal of the two dogs, which he painted with warmth and spontaneity, shows them as sentient beings in their own right. A perception enhanced by the catch-lights in Fox’s eyes along with his part-opened mouth.

Executed with Gainsborough’s characteristic light and painterly brushwork, the pair are clearly seen as family companions rather than working or sporting animals.

18th-century Lapdog mania in art

It wasn’t long before the trend in canine appreciation extended to the least energetic of the species. Lapdogs came into fashion with women in 18th-century France, particularly with popular figures such as Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s celebrated mistress, and Queen Marie Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI.

Both were well known for their love of papillons, pugs, bichon frises and Phalènes. Madame de Pompadour’s two Phalènes, Bébé and Mimi, were both portrayed by the French painter and artistic director at Vincennes and Sèvres, Jean-Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806). The extent of their indulgence is captured in a portrait of a Havanese. Sitting up on her shaven hind legs, a bow in her hair, she is performing a trick for which she has presumably been rewarded; two coins have been placed in the foreground. She has evidently stolen her master’s slippers.

But their time in the sun was short lived. The French Revolution was unkind to pure-bred lapdogs. Considered totems of the ancien régime, they were actively eliminated or released into the streets of Paris and became common dogs trained to do tricks for popular amusements.

The other popular lapdog of the day in European aristocratic circles was the pug. Introduced to Europe from China in the late 16th century, pugs were appreciated for their even temperament and sociability and for their willingness to act as canine hot water bottles – happy as they were to sleep on the feet of their owners at the bottom of the bed. Pugs even became the symbol of a secret society called the Order of the Pug.

George Stubbs

The unsurpassed master of dog portraiture in Britain was George Stubbs (1724–1806). His extensive study of the anatomical make-up of animals through dissections, which he documented with precise anatomical drawings, enabled him to bring portraits of single working dogs, and later lapdogs, to a new level of sophistication from the mid-1760s onwards.

Stubbs undoubted skills meant he was quickly able to acquire patrons looking for something new in the painting of the sporting life of horses and dogs.

The group of clients Stubbs appealed to were young, extremely rich and influential – deriving their wealth from country estates and their power from parliamentary seats.

Edwin Landseer’s Dog Portraits

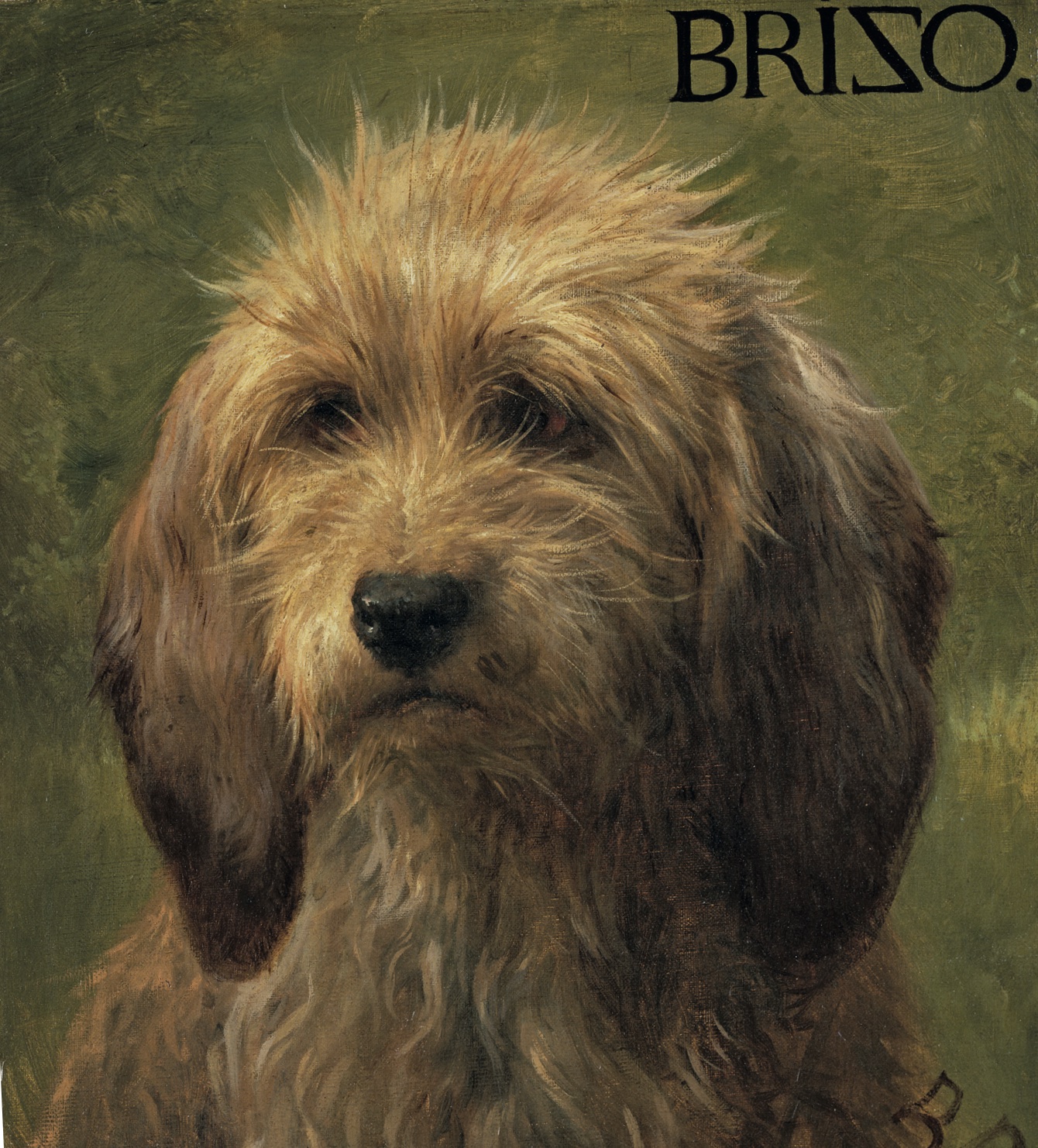

As a portrait painter of dogs Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) stands on his own. While contemporary sporting artists predominantly portrayed sporting dogs, Landseer developed a new brand that appealed to Victorian society.

Using humour and satire, his ability to tell a story with moral values echoed literature of the time. The image of the dog that he represented had strong parallels with the novels of Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, where dogs have feelings and intelligence.

Landseer’s ability to humanise his dogs was one of the principal reasons for his success with collectors and the Victorian public. In one of his most popular works, known as Doubtful Crumbs or Crumbs from the Rich Man’s Table, two dogs of different sizes are humorously juxtaposed as the black-and-tan terrier looks longingly at a bone guarded by a dozing mastiff.

The title refers to the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus as told in the Gospel of Saint Luke (16:19–31) and would have been fully appreciated by the Victorian public. When it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1859 critics from The Times reported “None but Landseer can thus render the human in the canine expression.” The idea of dogs acting out a scene was to become Landseer’s speciality.

Royal dogs in art

For centuries dogs have been associated with the British monarchy: Richard Lionheart and Henry II both kept pet pooches, and the court of Henry VIII was so overrun by dogs that the king had to prohibit large dogs from entering. Perhaps most dramatically of all, Mary, Queen of Scots, is even said to have hidden her small dog underneath her wide dress when she ascended the scaffolding for her execution.

Charles II famously allowed his spaniels to roam the grounds of the palace of Whitehall. In his diary Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), an administrator of the navy of England, described the king’s behaviour during a council meeting: “All I observed there was the silliness of the King, playing with his dog all the while and not minding the business….”

Although every British sovereign was passionate about dogs, Queen Victoria had her pets immortalised in portraits and photographs to an unprecedented degree.

Landseer and Queen Victoria

In 1836 a portrait of Victoria’s spaniel Dash, became the first royal commission given to Landseer – a relationship between patron and artist that transformed dog portraiture to a new level of sophistication.

Under Victoria’s patronage Landseer painted more than a dozen portraits of royal pets, mainly dogs. In his lifesize group portrait of Dash, Nero and Hector he positioned the dogs in a sumptuous domestic interior surrounded by the symbols of wealth. Landseer here introduces us to Queen Victoria’s favourite dogs and parrot, the low viewpoint making us feel part of their sumptuous and privileged world. Victoria described the painting as “the most beautiful thing imaginable” when she saw it before it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1838.

Landseer also gave Victoria and her husband Albert drawing and etching lessons during the early 1840s, enabling them to portray their own dogs. Both were competent artists – Victoria probably the more gifted.

Changing perceptions of Dogs

This public interest for Queen Victoria’s dogs went hand in hand with a changing perception of the dog in society. While some dogs were fortunate enough to be pampered in the grand houses of the nobility, the expanding middle and urban working class were becoming able to afford non-working dogs of their own.

However, many dogs lived in horrible conditions. Blood sports such as dog-fighting and bull-baiting were popular social entertainments attended by men from all social backgrounds. From a very young age, Victoria was actively involved in changing animals’ living conditions: in 1835, aged 16, she became the patron of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In 1840 she directed that it should enjoy the prefix ‘Royal’, a move that encouraged others to support the society.

In her modern kennels at Windsor Great Park all dogs got the same treatment, and she did not allow ear-cropping or tail-docking, which were common practice at the time. With the rising awareness of the mistreatment of dogs, blood sports were prohibited by an Act of Parliament in 1835. The kennels housed more than 100 dogs, among them breeds that were new to this country. Following royal example, dachshunds, Pekinese and Dandie Dinmont terriers became popular. The best loved of their dogs – Albert’s greyhound, Eos; Victoria’s Skye terriers, Islay and Cairnach; Victoria’s dachshunds, Waldmann and Waldina; the Sussex spaniel, Tilco, were all painted. Taking the lead from the royal family, dog portraits had finally come of age.

Dogs in David Hockney’s art

Some 150 years later, David Hockney painted a series of 40 paintings of his dachshunds, Stanley and Boodgie, over a two-year period beginning in 1994.

By portraying the two dogs sleeping, or at rest on their vibrantly coloured cushion, Hockney creates a strong sense of intimacy and immediacy. Before he began painting, the artist made several studies of the pair. In order to quickly sketch them he positioned piles of paper aound the house.

Hockney shows them behaving naturally, as pets at home, in a posture of total relaxation, as opposed to sitting like models for a portrait – in what has become an informal mutation of the 18th-century dog portraits of Stubbs and Gainsborough. He wrote: “They’re like little people to me. The subject wasn’t dogs but my love of the little creatures.”

Da Vinci’s Paws

Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) fascination with animals is well known. In the 1490s he planned to make a comparative study of animals and men, including their movements and feet. But there is one particular canine detail over which Leonardo obsessed: the paw.

Scotland, © National Galleries of Scotland

In a drawing executed in the early 1490s, he concentrated on the left forepaw of what is probably a deerhound, drawing it from a number of different angles.

In one drawing we see three separate studies of the same paw, including the five soft pads underneath. They are lively, sketchy renderings with the artist imparting an animated, almost electrical charge to the fur around the paw.

Fond Remembrance

The architect Sir John Soane (1753-1837) was devoted to his wife’s dog Fanny. Following the death of his spouse in 1815, the Manchester terrier became his constant companion. When Fanny herself died in 1820, Soane buried her in a lead coffin in the courtyards of their house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Two years later, Soane acquired a posthumous portrait of Fanny by the well-known animal painter James Ward (1769–1859). In classical pose, she sits on the capital of a column gazing towards a temple at the Parthenon in Athens.

Portraits of Dogs from Gainsborough to Hockney runs from now until October 15 at The Wallace Collection, Hertford House, Manchester Square, London, W1U 3BN. For more details go to www.wallacecollection.org