Tiffany lamps – the ultimate guide

Call it The Gilded Age effect (the HBO series set in 1880s New York), or the boom in maximalism, or just a yearning for pretty, shiny things, but there’s no doubt Tiffany lamps are back in vogue. In 2020, Christie’s in New York restarted its dedicated Tiffany sales having paused them in 2014, with most lamps outstripping their guide prices. It seems the poster child for art nouveau fashion is back and shining brighter than ever.

Call it The Gilded Age effect (the HBO series set in 1880s New York), or the boom in maximalism, or just a yearning for pretty, shiny things, but there’s no doubt Tiffany lamps are back in vogue. In 2020, Christie’s in New York restarted its dedicated Tiffany sales having paused them in 2014, with most lamps outstripping their guide prices. It seems the poster child for art nouveau fashion is back and shining brighter than ever.

John Holmes, director of Duke’s Auctions in Dorcester, which has a rare Dogwood design in its sale on December 8, said: “There has been a real recent shift since covid and the focus it brought on our home and what we surround ourselves with. When we were all forced to remain at home it certainly made us think about what we needed, what brings us joy.”

But while Louis Comfort Tiffany is synonymous with lamps, like William Morris in this country, the range of decorative arts which he was known for, from stained glass windows to vases, is vast. The renowned Tiffany Studios, which he founded in 1889, was a hotbed of creativity, producing some of the most exquisite and sought-after decorative pieces of the era.

Tiffany’s artistic beginnings

Born in 1858, in New York, son of Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902) founder of the fancy goods store that became the renowned jewellery and silver firm, he was heir to the Tiffany empire. But early on Louis refused to be defined by his father’s success.

Instead, aged 18, he declared he wanted to study art, working under the influence of such artists as George Inness (1825–1894), being exposed to the ideas of artists and intellectuals including Oscar Wilde who claimed there was no boundaries between art and interior decoration.

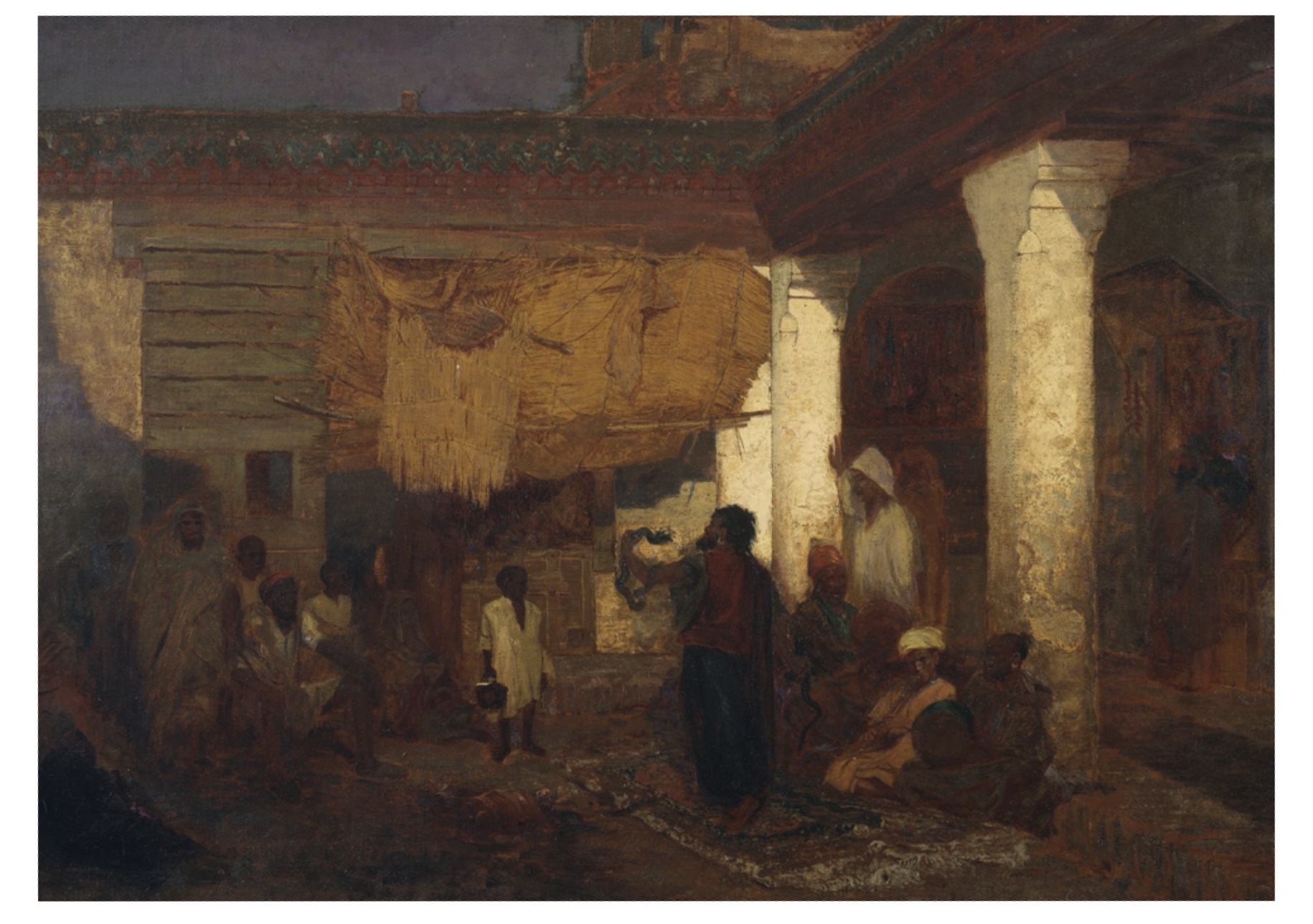

Having an income that allowed him to travel, Tiffany toured Europe, North America, and in 1870 visited North Africa, where he derived inspiration for his painting Snake Charmer at Tangier, Africa. The rich palette of earth tones recalls the work of his teacher, Inness, and reveals the beginning of his lifelong interest in colour and light.

The painting was among the orientalist canvases that Tiffany displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. In his travels, Tiffany also visited the glasshouses of Bohemia and Venice, providing a practical insight into skills what would serve him well when he returned to New York.

Into interiors

Soon after Tiffany met the American painter, interior designer and writer Samuel Colman (1832–1920) with whom he started several artistic movements and, with the painter Lockwood de Forest, formed Louis Tiffany and Associated Artists, moving from painting to the decorative arts and interiors, although he never abandoned painting.

In this he was greatly influenced by William Morris and the arts and crafts movement in the UK. Morris was convinced that industrialisation had degraded the work process, reducing the creative craftsman to an anonymous labourer mindlessly repeating unfulfilling tasks. But few companies on either side of the Atlantic could produce affordable art for the home, while retaining high standards and individual expression. Tiffany was able to succeed largely because his personal fortune allowed him to sacrifice company profits in the interests of artistic achievement.

Women were to play a central role in applying arts and crafts principles to social reform, creating many organisations to teach decorative arts. A number of educational ventures were set up across the country to arm women with creative skills. At the same time one such, the Western Reserve School of Design for Women, later the Cleveland Institute, was welcoming a new student – Clara Pierce Wolcott – a woman whose later role at the Tiffany Studios was to have a lasting effect.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company

The 1870s were boom years for a nascent interiors company. Public buildings, theatres, museums and mansions were being built across the country. Like Morris, Associated Artists designed wallpaper, tiles, hangings and fabrics often in Islamic or Celtic style but increasingly in the fashionable oriental style.

In 1882, President Chester Arthur commissioned Tiffany and Associated Artists to redecorate a number of the rooms at the White House, with Tiffany’s redesign of the Red Room decorated in line with the aesthetic movement of the 19th century.

In 1878, Tiffany set up a glass-making furnace to supply tiles and panels to Associated Artists and soon the Tiffany lead-glazed coloured glass window became the company’s signature design, often used to bring colour to an uninspiring view of the city. As time went by Tiffany found himself increasing fascinated by glass and its apparent endless applications. In 1881, he registered a patent for improvements in coloured glass windows, particularly the insertion of pieces with a metallic lustre.

In the 1870s both Tiffany and the fellow American glass designer John la Farge (1835-1910) both worked on opalescent glass which transmits little light. Tiffany’s glass tiles were designed specifically for use in lighting fixtures that soon became a feature of Associated Artists’ interiors.

His intention was to create objects of beauty for every American home, from stained glass windows to desk sets. But it was for his lamps that Tiffany went on to achieved lasting worldwide recognition.

Clara Driscoll

In recent years, the role played by Clara Wolcott Driscoll (1861-1944) in Tiffany lamp production has gained more recognition and appreciation, with her legacy in the world of decorative arts now widely acknowledged.

Initially, many of the lamp designs were attributed solely to Louis Tiffany, however, scholarly research and reevaluation of historical records have brought Driscoll’s work to the forefront.

After graduating from Cleveland’s Western Reserve School of Design for Women, Driscoll, then Wolcott, took up a position as designer for C. S. Ransom and Company, a Cleveland-based manufacturer of Moorish-influenced panels for use in interiors and furniture. Ambitious from the start she soon cast her net further afield moving to New York to continue her studies at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art School, which emphasised design for industry. She soon found employment at Tiffany Glass Company. Having learned the skill and intricacies of glass selection, Wolcott was forced to resign from the firm, as was required by company law, to marry Francis S. Driscoll in 1899, a man several years her senior.

Women’s Glass Cutting Department

After her husband died three years into the marriage, Clara was rehired to oversee the Women’s Glass Cutting Department (informally known as “the Tiffany girls”). The lamps were first marketed in 1895 with their bronze bases marked with the monogram of the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company and the model number. After 1900, ‘Tiffany Studios New York’ was used. Further models were introduced, many taking art nouveau themes for their inspiration. Tiffany soon realised that the harshness of the new electricity upset many people and made sure his lamps formed pools of soft, flattering light. But times were changing.

The New York Armory show of 1913 brought European modernism to New York and, by the 1930s Depression era, with functionality and sleek modernist styles in the forefront, the ornate lines of Tiffany products had fallen from favour. The swirling, multicoloured patterns, once seen as vibrant and new were associated with elderly aunts in fusty aparments. Interest in them renewed in the ‘50s and ‘60s only to fall foul of more modernism. Now art nouveau is riding high and the lamps’ popularity is shining bright.

The Tiffany peacock lamp

Another design likely to be by Clara Driscoll (1861–1944). Both she and Tiffany shared a love of peacocks with their brilliantly-coloured iridescent plumage, which appeared in almost every genre of his artistic production.

This particular lamp retains its original kerosene-burning fluid apparatus, as well as an electric bulb armature. Although incandescent lamp bulbs had become more widely available in the 1890s, most households, even those of the wealthy, were not yet wired for electricity. Tiffany originally designed his lamps with an oil-burning apparatus and an electric attachment, smartly predicting electric households would eventually become commonplace.

Stained glass windows

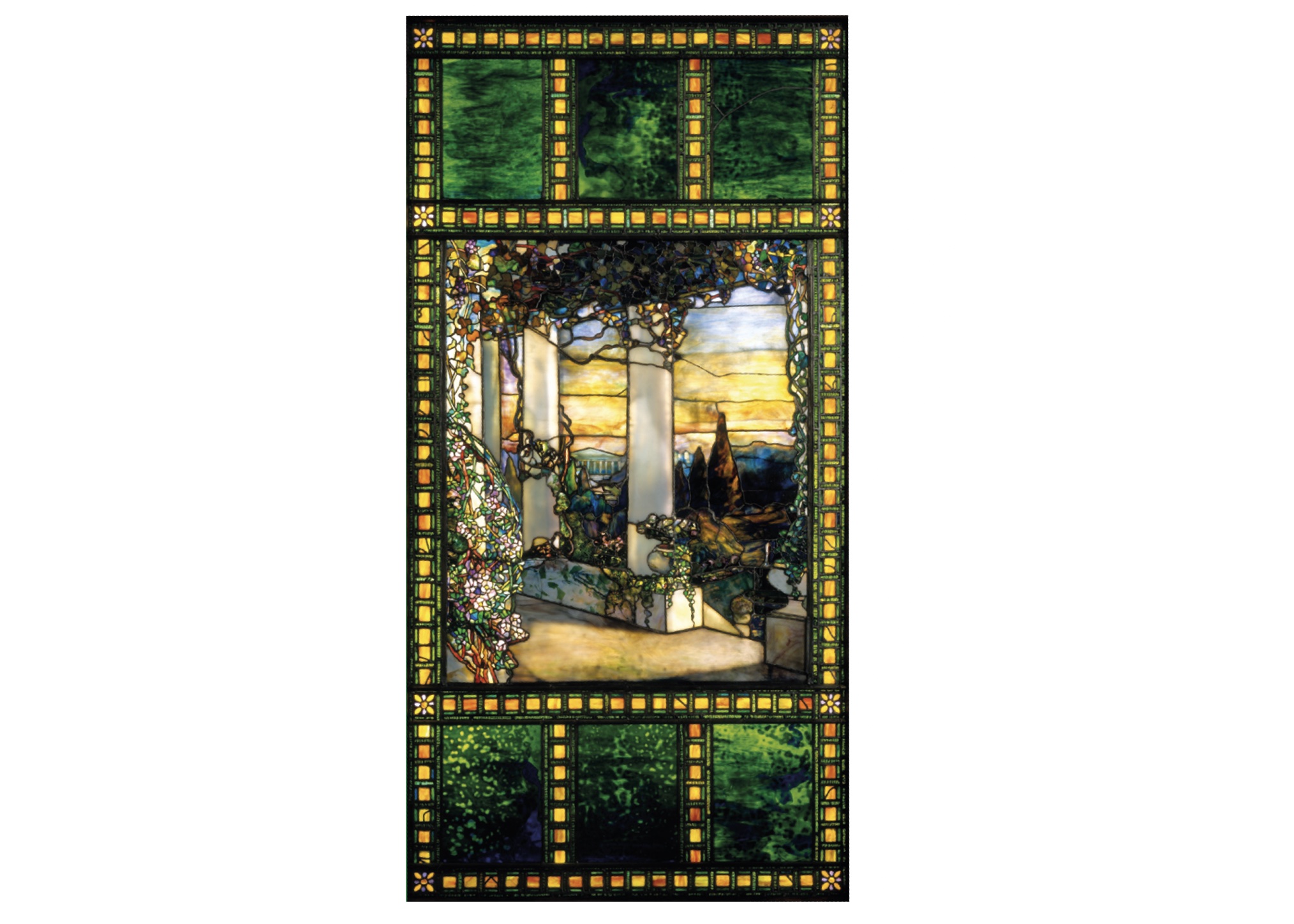

As well as his lamps, Louis Tiffany is known for his leaded-glass windows. In them can be seen the maker’s forward-looking abstraction and marble-like effects of the glass, the light-filled colours appearing as if created by the strokes of a painter’s brush.

Different effects were achieved by embedding tiny, confetti-like flakes of glass in the surface. The superimposition of several layers of glass on the back of the window added further depth.

Tiffany was commissioned by individuals and churches to produce stained glass and glass mosaics. When it came to the latter, Tiffany regularly risked controversy for favouring landscapes over traditional religious scenes.

In 1898, Tiffany was commissioned by the industrialist Howell Hinds to decorate his new Cleveland home with an art nouveau interior and glasswork.

One of the windows (above) was made up of thousands of richly-coloured glass pieces, arranged and layered to paint an idyllic threedimensional scene that would have warmly glowed in the afternoon sunlight.

Photographs show the placement of the window in the drawing room next to the fireplace in one of the opulent interiors Tiffany designed for the library and dining room.

Favrile glass

Tiffany soon began to collaborate with glass artists on new types of production, including the experienced British glassblower Arthur Nash, who he hired as a master glassmaker in the early 1900s. Nash developed the unique formula for Tiffany’s trademark Favrile glass, a recipe which was never shared with anyone, including Tiffany himself. Tiffany was enchanted by the new glass, writing: “After all the accomplishments of the Venetians, of Galle and others it was still possible to utilise glass in a new way that was often opaque and matt, with a surface that was like skin to the touch, silky and delicate.”

The effect was created by introducing various chemicals into the molten glass while in the furnace to produce multicoloured iridescence. The name Favrile was registered in 1894, deliberately named to sound French, expensive, and “handmade.”

From the outset, Tiffany used Favrile glass in mosaic panels, stained glass windows, and his artistic line of table and floor lamps. The range also extended to almond dishes, cigar jars and glasses. Interest in Tiffany’s glass was so intense it was soon copied in Austria and Bohemia, notably by Johannes Loetz.

Tiffany Lamps at Auction

With maximalism back in style, Tiffany lamps are once more gracing the finest interiors. Duke’s director, John Holmes, said: “It’s the old adage of scarcity and outstanding quality combined. Original Tiffany lamps were never mass-produced or machine made, always hand produced and only for a very limited time span around the turn of the last century.”

While previous demand for a high-quality Tiffany piece came from the States, today’s emerging buyer power is the Middle and Far East, he added. In general it is the floral designs which are the most sought after, with Driscoll’s Wisteria being a perennial favourite.

Surprisingly, only 12 Tiffany Studios lamps have ever cracked the $1m mark, with some 30 having crossed the $500,000 mark – many of which were Wisteria examples. But if auction figures are any indication, it is the Pond Lily – which sold for $3.37m at Christie’s New York in December 2018 (smashing its estimate of $1.8-$2.5m) – which is the most wanted. Rarity was the motivation for would-be buyers, with fewer than 14 examples known of that particular Pond Lily model in existence – five of which being in museum collections. Its rarity was no doubt due to its short production time of just 1902 to 1906.

Shape was also a factor, with the Pond Lily being in the preferred, rare, “globe” shape, which was a particularly difficult shape to master. Its artistic glass selection, patina on its bronze base, as well as strong synergy between base and shade, also adding to the high price.

But for collectors who don’t have $3m tucked away, what are the designs to look for? John Holmes continued: “One model to look for is the Greek Urn bronze lamp base, which can fit a 16in shade. Lamps without shades can go for a few hundred pounds. With an original shade, you may add up to ten thousand to that.”