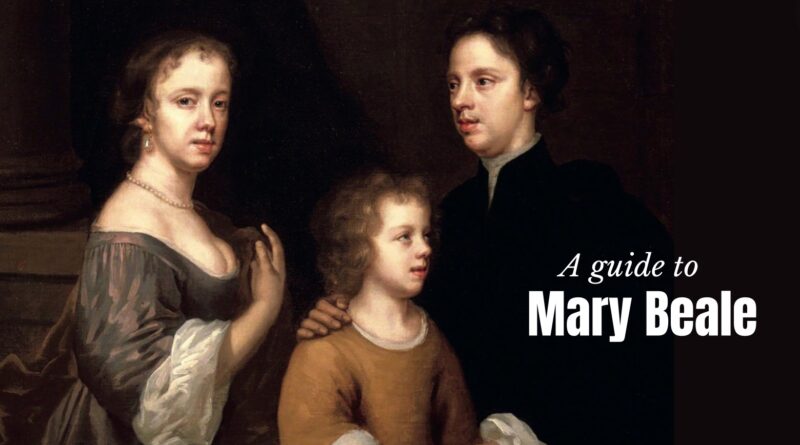

Mary Beale – an essential guide to the artist

For years female artists struggled to succeed in a man’s world. Not so the leading 17th-century portraitist Mary Beale whose husband and sons both worked for her. Antique Collecting went behind the scenes of an exhibition on the site of her former studio

Mary Beale’s studio

If time travel was possible and visitors to Philip Mould’s Pall Mall gallery turned the dial back to Restoration London, what would they see?

Shimmering up from the ether would be the studio of Mary Beale, an amenable family environment overseen by the matriarch herself – Mary Beale (1633- 1699). In contrast with other studios of the day – bustling with apprentices and assistants – the ‘paynting roome’ at the top of the house was a uniquely feminine space. Along with her two young sons, who variously helped her and amused the sitters, her husband worked alongside her mixing her paints, priming canvases, managing the business and looking at ways to lessen her load.

It was a genial style of working that clearly worked with some of the most important gentry of the day flocking to her studio, near The Golden Ball, at 18-19 Pall Mall. Today Beale’s home studio is the gallery of the host of BBC’s Fake or Fortune’s, Philip Mould, which is staging an exhibition entitled Fruit of Friendship showcasing 25 of Beale’s works from public and private collections, including some never seen before in public.

The exhibition sheds light on Beale’s progressive studio practices, highlighting its radical reversal of conventional gender roles. In an era when convention expected married gentlewomen to be deferential, modest and virtually silent, the exhibition revealed how Mary’s husband, Charles, dedicated himself to his wife’s career.

Philip Mould, who over the last 30 years has placed a number of Beale’s rediscovered works in public collections, said: “When we recently discovered the remarkable fact that our gallery is on the site of her London studio, our destiny with Beale felt even more complete.”

Suffolk-born Beale

Mary Beale was born Mary Cradock, at Barrow Rectory in Suffolk in 1633, the elder daughter of Revd John Cradock (c.1595–1652), a puritan rector and his wife Dorothy. As well as a religious man, Mary’s father was an amateur artist and member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company and his involvement in the nearby artistic scene of Bury St Edmunds makes him the likely candidate for being his daughter’s first tutor in art, a tradition seen in a number of early female artists, including Artemisia Gentileschi.

What artistic ambitions the young Mary harboured is difficult to know, but one thing is for sure after she married Charles Beale (1631-1705) in 1652, aged 18 – an act which usually sounded the death knell to female aspirations – Mary’s star began to shine.

Dear husband

Like his wife, Charles Beale was born into a puritan family in Buckinghamshire. Little is known of his education or early years until 1647 when he started to record his artistic activities in a notebook, Experimentall Seacrets found out in the way of my owne painting – a 24-leaf, leather-bound notebook with entries compiled between 1648 and 1663.

Bound by an artistic persuasion, the union also appears to have been a love match with Charles referring to his wife as his “Dearest and most Indefatigable Heart”.

Shortly after marrying, the couple moved to Covent Garden, later moving to Fleet Street, and began associating with a fashionable circle of artists, intellectuals and clergymen who later became the base of her patronage. In 1656, she gave birth to her first son Bartholomew (1656-1709) and four years later Charles (1660-1726). Until 1665 Beale’s painting remained purely amateur but, by 1664 Charles’ job at the patents office had become insecure and, with the plague threatening, the family left for Albrook, in Otterbourne, Hampshire.

Marital equality

At Albrook Mary wrote her Essay on Friendship. Both Mary and Charles strongly believed in the concept of equality between husband and wife. Without such, Mary believed, true friendship could not exist. She wrote: “…For when God had at first created him, it is not Fit said he, that Man should be alone, so then he gave him Eve, to be a meet help, and what can that imply but that God gave her for a Friend as well as for a wife.”

When the Beales returned to the capital in 1670 (Mary aged 38 and her sons aged 14 and 10) she put the theory into practice and set herself up as a professional ‘Face- Painter,’ becoming the chief supporter of her family in their rented house in Pall Mall.

London’s population in 1670 was around 500,000, making it one of the largest cities in Europe. In the aftermath of the Restoration of Charles II the capital was rife with artists and scientists keen to gain the ear of the court. It was a bustling cultural centre, with theatres, taverns, and coffeehouses providing entertainment. As before, the Beales’ circle of friends included courtiers, intellectuals, artists and literary figures. These were the men, and their wives, who Charles termed ‘persons of quality’ in his studio records, whose formal portraits Mary would be commissioned to paint.

Amateur to professional painter

But in the 1660s it was one thing for a woman to paint portraits of her family and friends for love rather than money, but it was a different proposition for her to invite male strangers into her home for commercial purposes.

To achieve respectability Mary had to call on and expand her network of friends. In this way the ‘persons

of quality’ who came to sit for her could be perceived as guests, rather than paying customers. She also made the most of the courtly culture of gift exchange, allowing her to give portraits and texts as gestures of affection, but also as payment in kind for favours and loans.

Philip Mould said: “Mary Beale pioneered a practice that was both supported by, and was reliant on, her immediate circle; from friendship and trust established within the home between her husband and children, to the bonds she created throughout her wider circle of neighbours, friends, and fellow artists.”

One of the key friendships she enjoyed was with Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680) Charles I and II’s court painter. By 1672, Lely, who Mary may have met when he visited Suffolk in the 1640s (and some say who encouraged her to paint), had visited her London studio and later allowed her to study his painting techniques. This was a remarkable opportunity and she even created a market selling replicas of his portraits. In fact, so similar are their styles, Mary’s work has on occasion been wrongly attributed to Lely.

Life in Pall Mall

Mary’s circle also included members of the puritan clergy, notably Edward Stillingfleet, who was to become Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral and Bishop of Worcester.

Religion was an important element of family life. The diaries of the Beales’ close friend Samuel Woodforde reveals Mary as a “sympathetic and hospitable” friend and the household as a ‘puritanical’ one, regularly setting aside 10 per cent of their income for the poor.

But despite the charity, her prices were competitive: £10 for a three-quarter-length and £5 for a half-length portrait. As they grew up, both her sons would assist her by painting time-consuming drapes, well-detailed costumes and Baroque-style cartouches. Mary also employed and trained a number of female studio assistants, including Sarah Curtis (1676-1743) who later pursued a successful career as an artist. While Bartholomew would become a physician, Charles went on to find success in miniatures.

Busy times

Meanwhile, Charles continued to assist with the practical side of running a studio, including chemical experiments to mix expensive colours more cost- effectively, in order to make commissions more profitable. (As well as painting on expensive imported linen Mary also used sacking, and even, at times, on onion bags and striped bed ticking fabric.)

In 1677 alone, her most profitable year, Charles’ records show Mary was commissioned to paint 83 portraits. While six years previously her annual income totalled £118 5s., in 1677 it had risen to £429.

Her workload was relentless. In 1677, a snippet of her schedule records:

“1st Mr Moore, third sitting two hrs.

Feb 3rd Mrs Twisden’s picture.

Feb 5th Mrs Fitzjames face and breast finished.

Feb 7th Mr Rog Twisden’s face carried a good way.

Feb 8th Mrs Twisden third sitting.

Feb 9th Countess of Derby face in little well laid in.

Feb 10th Countess of Derby face and breast.

Feb 12th Countess Derby scumbled and re-touched.

Feb 13th Mrs Twisden’s face laid in for finishing.”

Decline in popularity

But the good times couldn’t last. The decline in demand for Mary’s portraits coincided with the death of Lely in 1680. By 1688, the year of the ‘Bloodless Revolution’ that deposed James II in favour of his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, her style was out of favour. She died in London in 1699 and was buried in St James’s Church, Piccadilly. Charles outlived his wife by five years.

In an era stacked high with obstacles to women’s fulfilment both artistically and economically, her

life and career from the daughter of a rural curate to professional portraitist is a nothing short of remarkable.

Fruit of Friendship is on at the Philip Mould Gallery, Pall Mall until July 19. For more details go to www.philipmould.com. Beale’s work can also be seen in the Now You See Us exhibition at Tate Britain – www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-britain, while Moyses Hall in Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk has a fine collection of her paintings.

Mary Beale at Auction

Until the 1975 exhibition The Excellent Mrs. Mary Beale at the Geffrye Museum (now Museum of Home) in London, Beale’s name had almost been assigned to the scrapheap. Not so today. As museums rush to redress the balance of women painters in their collections, there has been a frenzy to acquire her work.

One noteworthy sale was at the Essex auction house Reeman Dansie which catalogued a picture of a young boy with tousled chestnut brown hair and twinkling brown eyes as “18th-century Italian School”, giving it an estimate of £400-£600. But eagle-eyed collectors realised its similarity to a number of known portraits by Beale of her son Bartholomew, one of which is on display at Tate Britain, with another selling for £75,000 at Sotheby’s in July 2019.

Its overblown, carved Florentine frame was unidentified but did not fool Philip Mould who recognised the sleeper as a lost work by Beale.

After strenuous competition with the bidding lasting four minutes, it was eventually knocked down at £100,000, representing a new high for the artist at auction. To show the appreciation in prices for her work, a portrait of her younger son, Charles Beale, aged around 20, sold for just £8,365 at Bonhams’ sale in 2004.

Carter the Colourman

Charles Beale’s almanacs, which documented his wife’s professional and personal affairs in minute detail, are a lasting and invaluable resource.

They are particularly insightful into the technicalities of oil painting of the time. Details record the purchase of 2lbs of ‘excellent deep Terra Vert at 4s 6d a pound’ which was mixed with linseed oil and stored in a pig’s bladder.

One of the merchant families Charles called on for materials were the Carters, made up of a father-and-son selling team who became friends.

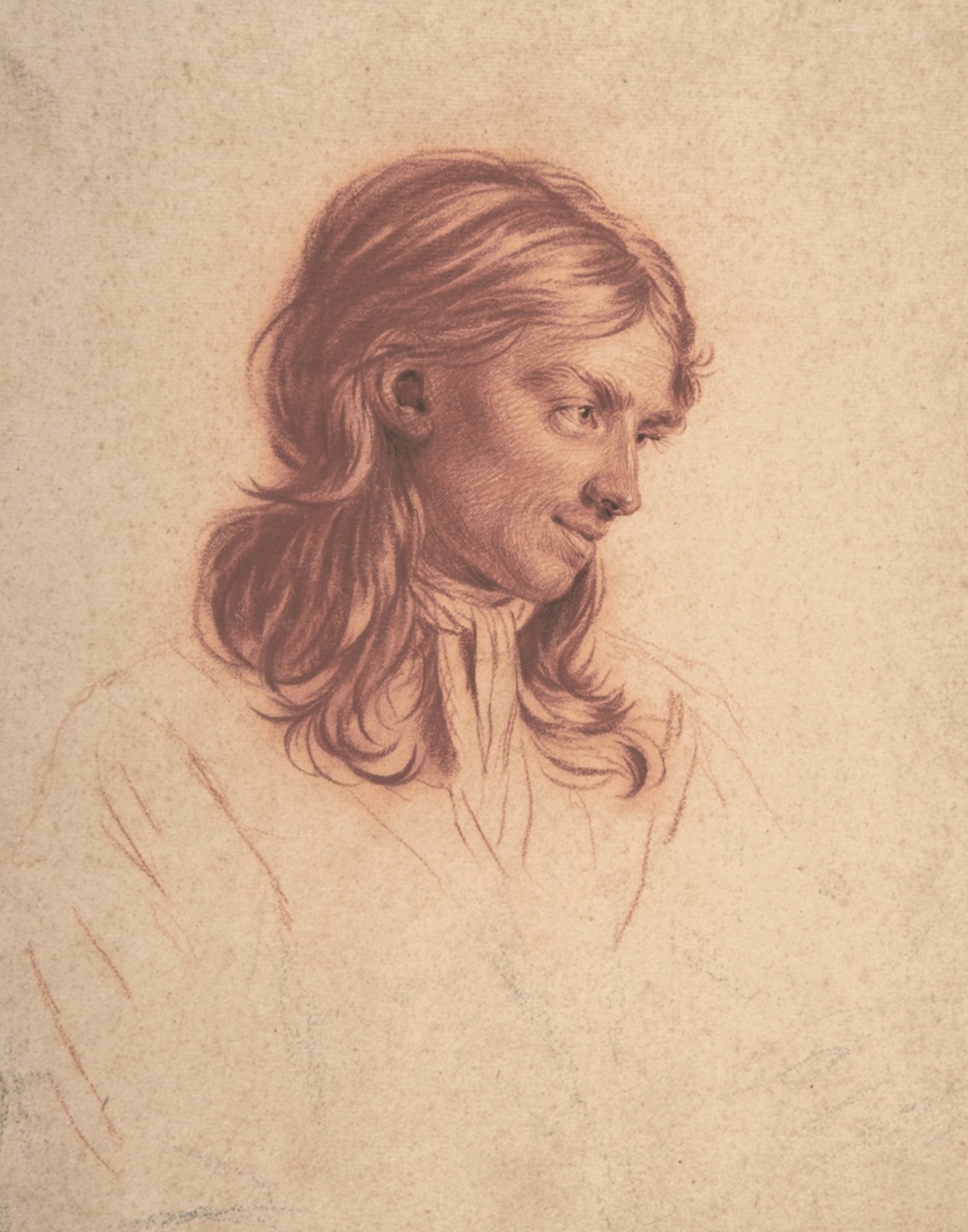

A red-chalk study of son George Carter is by Mary’s son Charles Beale the younger who worked on 30 pictures between 1676-1677. He showed such promise he was sent to Thomas Flatman in 1677 to learn the skills of a miniaturist (his miniatures occasionally appear for auction today).

Charles perfected his draftsmanship in drawings, like the one above, made when he was about 20. His choice of red as the primary tone is striking, and its effect is strengthened by black touches that define the pupils, nostrils, and ear.

Beale good factor

Tate Britain is currently hosting an exhibition celebrating 400 years of women artists from 1520 to 1920, including work by Mary Beale who joins the roll-call of 100 trailblazers.

Other leading lights include Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) who, with Mary Moser (1744-1819), were among the two female founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768.

The exhibition starts at the Tudor court with Levina Teerlinc (1510-1576) the Flemish-born painter who was

the most important miniaturist at the English court between Hans Holbein the Younger and Nicholas Hilliard. The exhibition brings together her miniatures for the first time in four decades, along with Esther Inglis (1571-1624), whose manuscripts contain Britain’s earliest known self-portraits by a woman artist.

Moving into the 17th century, focus turns to one of art history’s most celebrated women artist: Artemisia Gentileschi (1593- 1653) who created major works in London at the court of Charles I, including the recently rediscovered Susannah and the Elders, 1638-1640. Alongside Beale’s achievements, the success of two contemporary female portraitists –Joan Carlile (1606-1679) and Maria Verelst (1680-1744) – are considered.

Tackling nudes

A gallery spokesperson said: “These women’s careers were as varied as the works they produced: some prevailed over genres deemed suitable for women like watercolour landscapes, flower painting and domestic scenes. Others dared to take on subjects dominated by men like battle scenes and the nude.”

Like Mary Beale, some women did succeed in carving out a career including the miniaturist Sarah Biffin (1784-1850), who painted with her mouth, having been born without arms and legs.

The work of the botanical illustrator Augusta Withers (1793-1877), who was employed by the Horticultural Society and went on to be one of the founders of the Society of Female Artists in 1857, is also celebrated.

The exhibition also considers women’s connection to activism, including the satire Woman’s Work by the artist and humourist Florence Claxton (1838- 1920). The life and work of the English educationalist and artist, Barbara Bodichon (1827-1891) who campaigned for women’s rights – resulting in women being admitted to the Royal Academy Schools – is also brought into focus at the exhibition, which runs until October 13, 2024.