Tang Dynasty horses – the essential guide

Valued for their strength and endurance, horses symbolised power and status in ancient China and were even believed to transport souls to the next world, writes Allen Wang

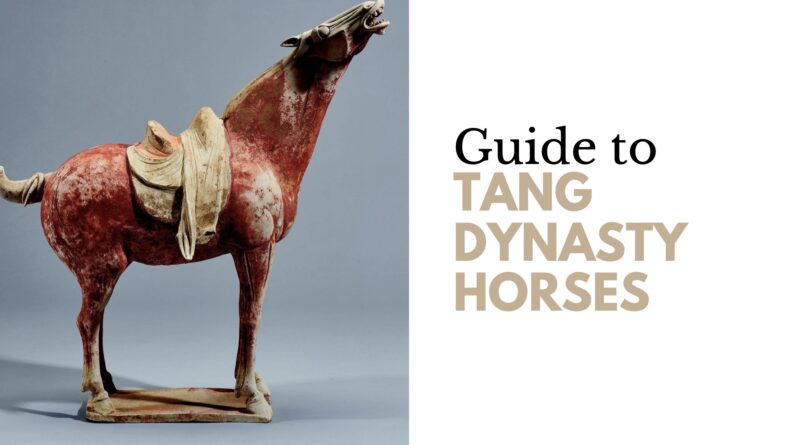

Tang horses are among the most famous works of Chinese art. For the collector, they have endless appeal, their stylised arched necks, pricked ears and strong bodies exude confidence, distinction and charm.

These ancient Chinese pottery steeds are found in every kind of decor: minimalist, country, French, even deconstructivist. Their appeal is universal.

The equine depictions are often in frantic positions: whinnying with their heads raises and nostrils flared, or twisting around to get at something on their backs.

A culture and and appreciation of horses in China dates back to the Shang dynasty (1600-1100BC) when real horses were buried with the emperors, and horsedrawn chariots were a sign of high social status, as well as being the premier weapon of war.

In about 210BC, the Qin dynasty decreed that the Chinese custom of burying favorite steeds (or wives) alive in the tombs with their aristocratic masters was no longer necessary. Rather, a symbolic sacrifice would suffice.

Regions of Production

Tang horses were made in multiple workshops across China with each location having its own style, and bearing the invisible marks of the potter’s geographic differences via the clay used. An appreciation of the colour and rigidity of the clay, as well as the shape and forms, adds a depth of appreciation.

Chang’an Horses from the Tang capital were strong and steady in proportion, with all three types of clays widely adopted.

Feng Xiang Mounts from west of Shaanxi province are finely sculpted, mostly in prancing position with a small head, strong head or turning head, beautiful contours and movement, made in a mixture of red and grey pottery.

Luo Yang One of China’s oldest cities where the majority of sancai (three-colour) glaze horses were produced as well as unglazed horses with more movement, in a streamline and lively manner. Shan Xi

A plateau province in the north of China that produced deeply carved horses, with strong lines and meticulous details on a powerful body, some with a removable blanket.

Gan Su The province in northwest China was responsible for round-bottomed animals, mostly in standing position with no movement, the overall figure is strong and weighty compared to other regions.

Earliest Horses

In the first century BC, two Chinese armies travelled to the western kingdom Ferghana in search of “heavenly horses”. They discovered the finest mounts then known, which were apparently infected with parasites that caused them to “sweat blood” from their pores.

These sought-after Bactrian horses were sent in great numbers as tribute to the emperor and immediately caught the imagination of both the ruler and his court. The animals became associated with dragons, animals capable of carrying humans to the land of the immortals.

Once acquired, horses were well looked after on state-controlled grasslands and stables where they were kept in cool sheds in summer and warm ones in winter.

Their manes were kept trimmed, their hooves cared for, and in battle, they wore blinkers and ear protectors to minimise the effects on their nerves of the noise and action of the battlefield.

Bactarian Horses

Horses soon became especially prized by rulers of the Han dynasty for their military value, at a time when cavalry warfare was used to fend off frequent attacks of nomadic invaders.

Chinese statuary and paintings indicate the streads had proportionally short legs, well-developed barrelthick necks and well-shaped heads. This equine type occurs also, as might be expected, in ancient Bactria, lying, as it did, almost next door to Ferghana.

In ancient evidence, such a horse can be seen on a gold medal struck by Eucratides, a Greco-Bactrian king of the second century BC (right).

Tang Dynasty Horses

But it was the “golden age” of the Tang dynasty (618-907) – one of China’s most cosmopolitan periods – that the horse ascended to its iconic status.

This was the time when ideas and art flowed into China on the Silk Road along with commercial goods reflecting influences from Persia, India, Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East.

At the beginning of the Tang dynasty the government owned some 5,000 horses. Private breeding developed in northern China, especially in eastern Gansu, Shenxi and Shaanxi, when the government decreed that all militiamen, most of whom belonged to great noble families, should have their own mounts.

Before long, public stud farms were established, soon becoming so successful that by the middle of the seventh century the government owned 700,000 horses, and equine cultural reverence was assured.

Polo Games

The love of horses also spurred the adoption of the Iranian sport of polo among the Tang elite, meaning horses became among the most desirable and important creatures of the day. Poets and painters, sculptors and potters all paid homage to them. Lavish displays of pottery horses and other artefacts began to adorn the insides of tombs where brightly-coloured tomb figurines were made from low-fired earthenware and intended exclusively for burial. “The potters made an incredible range of models, including entertainers, domestic workers, mothers with children, aristocratic ladies, soldiers, farm animals, ritual objects, cosmetic boxes and utilitarian vessels,” Lark E. Mason wrote in Asian Art (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2003).

Alongside the horses, Central Asian and Türkic nomads were depicted as horse grooms among the other mingqi (tomb figures) in Tang-era tombs.

Horse Power

Advances in technology in the Tang dynasty, including the use of moulds, allowed production on an unprecedented scale.

This, in turn, made mingqi accessible to those outside the highest social ranks for the very first time, and Tang horses lost their status. While they exerted fascination among some Western collectors (see Degas’ portrayal of the painter Pierre-Joseph Redoute in front of a cabinet holding a Tang horse) it wasn’t until much later that Chinese dealers were alerted to the West’s growing fascination with them.

In 1989, an auction record was set when a Japanese dealer paid a world-record £¾m at Sotheby’s for a glazed specimen that had been stashed away by the British Rail pension fund.

However, with prices falling back in recent years, would-be vendors may be advised to hold their horses, but for others now could be the time to buy.

Allen Wang is an art collector and founder of SACA (Society for Ancient Chinese Art).

Collecting Tang horses

Gallery owner Midco Lam offers the following advice on Chinese equines:

• Do not rush to purchase, instead take time to learn and study to help make the best decision.

• Visit museums, submerge yourself in relevant texts and, most importantly, seek professional advice from experienced and reputable dealers.

• Enjoy the piece and its history, appreciate the rewards of connoisseurship, have fun during the collection process, rather than focusing on monetary gain or loss.

Midco Lam is the daughter of Mama Lam who established Lam’s Gallery in Hong Kong in 1988 specialising in early Chinese pottery from the Han to Tang dynasty.

Lam’s Gallery can be found at 3C, Yally Industrial Building, 6 Yip Fat Street, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong.