Guide to reproduction Chippendale furniture

Few of us will ever own an original Thomas Chippendale but luckily reproduction Chippendale furniture created by the Victorians and Edwardians offer his iconic designs at a fraction of the price, writes James Driscoll of www.antiquesworld.co.uk.

Lasting legacy of Chippendale

With a number of events running throughout the UK to mark this year’s tercentenary of Thomas Chippendale, now is a good time to consider the cabinetmaker’s lasting legacy, from his somewhat humble birth in the Yorkshire town of Otley in 1718, to his global and enduring influence. (Even the German American architect and designer of the Barcelona chair, Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) said: “A chair is a very difficult object. A skyscraper is almost easier. That is why Chippendale is famous.”)

Chippendale’s enduring appeal

One of the reasons for the enduring appeal of Chippendale is the longevity of the Director. Published in 1754, The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director continued to influence cabinetmakers across the country (and beyond) throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Designs were wholesale copied by cabinetmakers, usually to order from pictures in the catalogue, for their own clients. They were also tweaked to meet the fashions of the day.

Population explosion

During the first half of the 19th century, the population in England more than doubled and the demands for furnishings strained the output of traditional cabinetmakers. Faster, cheaper manufacturing methods and techniques were needed for the industry to meet the demands. Design objectives changed from merely satisfying the demands of fashion and taste to also limiting the number of parts required to be made and increasing their ease of assembly.

Although much of the new machinery was invented during the late 18th and 19th centuries, cabinetmakers were slow to adopt these innovations. What helped the artisan more than the introduction of new machines was a new way of working. Shop methods replaced the traditional apprenticeship system, meaning workers only learned the production skills required for the task in hand with no one person taking responsibility for the overall piece.

Influence of George Smith

Similar to Chippendale’s Director and no doubt influenced by the catalogue, a pattern book was published by George Smith in 1808 that captured the fashions of the era. The book was called A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration. It is thought to be the first work in English in which the term ‘interior decoration’ was used.

The book popularised the Regency style which suited the villas and terraces being built in the UK to accommodate the growing population. It also brought back to the fore the Chinese and gothic style last seen in Chippendale’s Director.

Gillows of Lancaster

Gillows of Lancaster, the successful cabinetmaker’s shop founded by Robert Gillow in 1703, used the Director as an inspiration well into the late 19th century. In 1757, his son Richard became a partner and the firm took the name Robert Gillow & Son. In 1764, a permanent London branch of Gillows was established at 176 Oxford Road, now Oxford Street, by Robert’s other son, Thomas Robert Gillow with the intention of capitalising on the capital’s new class of wealthy buyers.

The firm’s reputation grew, until it became known as one the best cabinetmakers of the day. Quality was paramount. From the 1740s, Gillows had chartered ships to import mahogany from the West Indies to ensure the quality of its wood, using only slow-grown solid timber (Chippendale preferred to use first-growth mahogany in his designs).

Gillows and Chippendale’s Director

Richard Gillow was one of the original subscribers to the Director and its influence is clear. Under his direction, new workshops were built in both Lancaster and London and furniture ordered in London was sent every week from Lancaster.

Design choice

From the mid-1750s, as well as the Director, he was able to draw on the designs of fashionable new furniture based on plans sent to him by his cousin James, a journeyman working in London. Customers could choose furniture from Gillows’ design books, the Director, or even have furniture made up from their own sketches. Several chairs were based on Chippendale’s Director, including “Chinese”, “Gothic” and “French style” and adapted rather than copied by the Lancaster firm, but rarely slavishly copied.

Practical choices

Due to the firm’s shortage of carvers, in addition to its longstanding preference for practical solid furniture,

carving was usually restricted to a few ornaments on the chair back, leg and arms, at odds with Chippendale’s

ornate style. However, in 1765, Richard Gillow wrote to a customer asking if he would be agreeable to reproduction furniture in the Chippendale style, as he owned the book of patterns and would be able to “execute and adapt them”.

Gillows was also an incredible maker of furniture in its own right, including the trou-madame (a ladies’ version of a billiard table); revolving top library table and a patented telescopic dining table.

Towards the late-Victorian era, with perilous finances due to the influx of mass-produced furniture, Gillows joined forces with Waring of Liverpool and, in 1897, Waring & Gillow was born. Despite diversifying into the new luxury liner

market, Waring & Gillow also soon faced financial troubles. It was taken over by Maple & Co, to become Maple, Waring and Gillow, uniting three of the era’s major cabinetmakers.

Gillows’ marks

Unfortunately a large amount of Gillows’ furniture was not stamped, so it is common to see many pieces wrongly attributed to Gillows, due to their similar style and design. However the Gillows’ stamp can sometimes be seen under table tops, on the top edges of drawers, or the back legs of chairs. On occasions the signature is written in pencil under drawer lining by the firm’s cabinetmakers.

The earliest marks were in the form of the printed label ‘Gillow and Taylor’ but these are rare because, over time, many fell off or were damaged. The ‘Gillows Lancaster’ stamp was seen from the 1780s until the 1850s/60s, when it was changed to ‘Gillow’. In the 1860s, the mark consisted of a capital ‘L’, and a serial number, with the words ‘Gillows Lancaster’. Late Victorian pieces were stamped ‘Gillow & Co’ and, after the merger with Waring, ‘Waring & Gillow’, sometimes evident on brass fittings or locks.

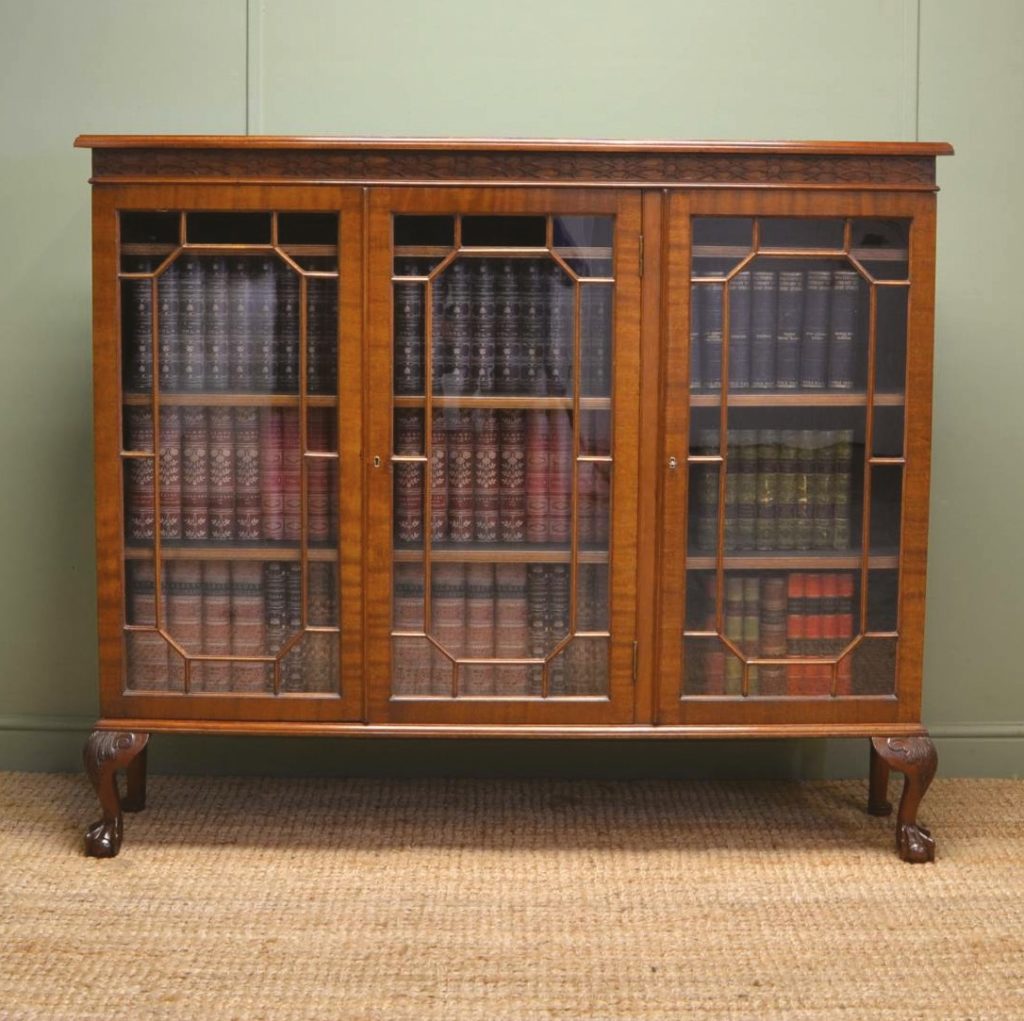

Reproduction Chippendale furniture

Victorian cabinetmakers readily adapted Chippendale’s designs, adding more fashionable features of the day

including ball and claw feet and cabriole legs. They also tried to add comfort and usability to the furniture.

Success of Maple & Co

Maple & Co was one of the largest and most successful British furniture retailers and cabinetmakers in the Victorian and Edwardian periods. It was well known for its quality craftsmanship and specialists who adapted old designs, bringing them up to date with modern trends. It produced many quality pieces of furniture in the style of both Hepplewhite and Chippendale, but was also well known for its arts and crafts furniture.

World’s largest furniture store

The company was established by the Surrey shopkeeper John Maple who opened a furniture shop in London’s Tottenham Court Road. But it was his son John Blundell Maple who pushed Maple & Co to greater success. With his skills in business, by the 1880s it was the largest furniture store in the world exporting fine antique furniture around the world. In fact by then the reproduction industry had become so large that, in 1884, the magazine Cabinet Making and Upholstery reported: “the making of antiques has become a modern industry.”

Reproduction Chippendale or original?

So how do you tell the difference between an original period and Victorian copy?

Original pieces of Chippendale furniture from the Georgian period were built by hand, so there will be very slight differences in shapes on backs of chairs or carvings (although these will be hard to detect as the carpenters were very skilled).

Spot the differences

The corner blocks and joints of earlier pieces will have saw marks and be slightly more rough to feel; the cabinet brassware will be more solid and of a better quality; pieces will include hand cut pegs in their construction and you will see a patina in the finish that you cannot reproduce.

The timber used on early pieces, such as Cuban mahogany, will have come from slower-grown trees and, therefore, be more dense, heavier and of better quality and have a brighter vibrant grain.

Having said that, the quality of later reproductions will still vastly outstrip the quickly-grown, poor quality timber used in today’s furniture.

Machine marks

The corner blocks of later copies are sharp and usually polished, as machines were used in the construction.

While the chair backs and legs will be exactly the same in shape, the carvings will also be both sharper looking and sharper to feel.

Chippendale today

Maple and Co., Waring and Gillows all adapted Chippendale’s designs to a greater or lesser extent.

While the late Victorian reproductions are of high quality, they lack the fine-crafted, hand-cut details and aged finish found in early Chippendale pieces and, obviously, do not command the prices of a true period piece.

These days it is almost impossible to find genuine furniture by Chippendale, not least because he didn’t use a maker’s stamp, so verifying his pieces or those of his workshop, can only be proven by original documentation such as a sales ledger.

Chippendale’s timeless appeal

Late Victorian and Edwardian Chippendale pieces represent extremely good value for money. The Chippendale style is timeless and suits any interior. As such it is increasingly popular with a younger clientele who is just starting to collect antique furniture but don’t want to break the bank.

LAPADA member James Driscoll runs the Lancashire-based antique furniture business Antiques World, which specialises in high-quality British antiques. For more details visit www.antiquesworld.co.uk.