Experts Choice – the best Antique Clocks

With their exquisite design and intricate craftsmanship, we asked seven horological experts to take some time out and tell us which antique clocks they would love to get their hands on.

James Stratton is Bonhams’ Director of clocks

James Stratton is Bonhams’ Director of clocks

Humpbacked carriage clock

I would, without hesitation, ask for this exquisite silver humpbacked carriage clock by Jump of London. With its pebble smooth edges and sleek lines, it’s hard to believe that it was made during the Victorian era. It is hallmarked for London, 1893, but follows an absolutely timeless design that could date from 1820, 1920 or even 2020. At just 15cm (6in) high it can sit on any desk or mantel piece as a constant companion.

And look at that dial – silver and gold are made for each other and both are set off by the blue of the night sky as the hand-engraved moon follows its nightly course across the dial every 29 and a half days. Smaller dials flank the gold signature plaque and show the day and date.

Humpbacked carriage clocks are incredibly rare to find on the open market – others were made by Breguet and Cole – but this particular example is notable for the survival of the original gilt-tooled green leather travelling case and the original solid silver safetywinding key.

It has already made people happy for over a century and would make an exquisite present at any time in the future.

Ben Wright is the Antiques Roadshow clock expert and a former head of Christie’s clock department. Today he runs a business, Ben Wright Exceptional Clocks, specialising in top-level clocks in Gloucestershire

Ben Wright is the Antiques Roadshow clock expert and a former head of Christie’s clock department. Today he runs a business, Ben Wright Exceptional Clocks, specialising in top-level clocks in Gloucestershire

Henry Jones Clock

Henry Jones was a great London clockmaker and, for me, also a man of immense character. Of course I know nothing about Henry’s character, no one ever will, so I have to draw on his clockmaking style and the Clockmakers’ Company records.

He lived 53 years from 1642 to 1695; he had a wife, Hannah, and a son, Henry and he worked in the Temple, just off Fleet Street.

I particularly like the entry in the Clockmakers’ records which read he: “Had a great quarrel with the fiery clockmaker John Nicasius, in which the latter was proven to be wrong.” I believe this clock is an excellent reflection of Henry’s character.

The case stands only 30cm (11.5in) high, it has simple mouldings, yet a masculine bearing and well-balanced proportions.

The ebony veneers have rare sumptuous silver mounts, the dial spandrels are also silver and, on the back of the movement, his name isn’t splashed all over like some clockmakers were wont to do, it’s quietly signed Henricus Jones.

In later years he gave £100 “for the use of the poor”. A huge sum. I think he was a good man – and, of course, a very brilliant clockmaker.

Catherine Southon is a familiar face on various BBC antiques shows and runs her own auction house, Catherine Southon Auctioneers

Catherine Southon is a familiar face on various BBC antiques shows and runs her own auction house, Catherine Southon Auctioneers

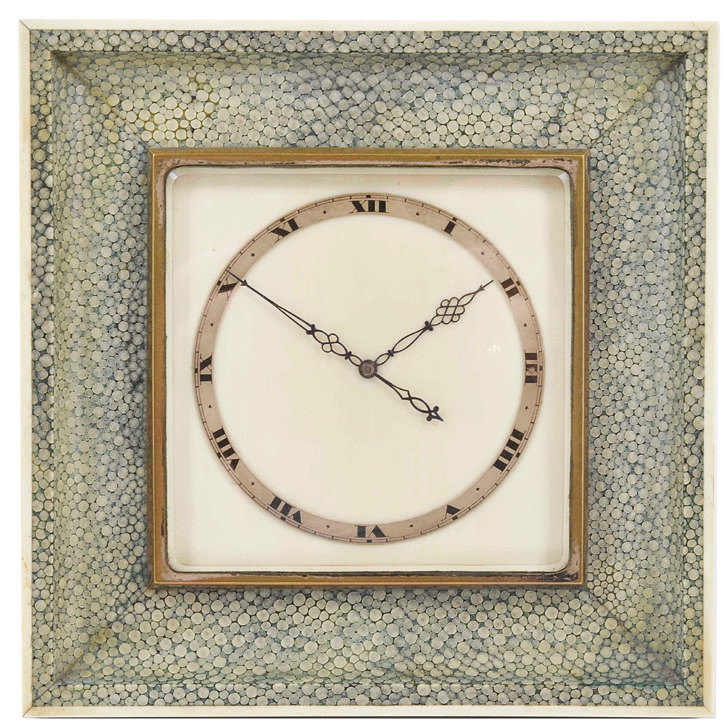

Art Deco Shagreen and Ivory Clock

We sold a collection of art deco and 20th-century design belonging to designer Richard Channing. Richard had collected decorative arts over five decades and had impeccable taste and a good eye, having picked up some great pieces of 1920s design during the war years before they became expensive.

One of the objects he had owned was a stunning art deco shagreen and ivory clock. It was incredibly simple in its design – square with an easel back – but the shagreen and ivory worked in perfect harmony and looked so elegant. I have always loved shagreen, or galuchat which is not made from shark skin (as many people believe) but, more commonly, stingrays.

One of the objects he had owned was a stunning art deco shagreen and ivory clock. It was incredibly simple in its design – square with an easel back – but the shagreen and ivory worked in perfect harmony and looked so elegant. I have always loved shagreen, or galuchat which is not made from shark skin (as many people believe) but, more commonly, stingrays.

Although it was common in the 18th century and earlier, it was during the 1920s and 1930s that the material was widely used in domestic design and can appear on anything from furniture to hairbrushes and anything in between.

The clock had a simple Swiss movement but whether the clock worked or not seemed irrelevant, it was just a very attractive piece of design. I fell in love with it the minute I saw it and really regretted not buying it. It sold for £600 (plus premium) and was worth every single penny.

The market for clocks today is certainly not as strong as it has been in years gone by. Buyers today prefer style over tradition, of which this beautiful shagreen art deco clock is a perfect example.

Jonathan Betts is senior curator of horology at The Royal Observatory and curatorial adviser to the Harris (Belmont) Charity

Jonathan Betts is senior curator of horology at The Royal Observatory and curatorial adviser to the Harris (Belmont) Charity

Pendulum Wall Clock

For me, it would have to be the absolutely stunning early pendulum wall clock, made in London, c.1660, by Edward East (1602-1696), now in the Lord Harris Collection at Belmont in Kent.

For me, it would have to be the absolutely stunning early pendulum wall clock, made in London, c.1660, by Edward East (1602-1696), now in the Lord Harris Collection at Belmont in Kent.

The pendulum was only introduced into clockwork just a few years before and genuine and original pendulum clocks from this period (known as the “Golden Age of English Clockmaking”) are fantastically rare. But this clock is not just rare, it’s aesthetically such a pleasing thing; housed in an ebony-veneered, ‘architectural’ style case (all the rage in furniture at this period) the clock is, to my eye, of sublimely beautiful proportions.

As for the maker, Edward East, whose amazingly long life spanned virtually the whole of the 17th century, was at the forefront of the early Golden Age in London. As a founding member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in London in 1631, there can’t be many better names to have on a clock from this period.

It is well known that these days brown furniture, and wooden cased clocks in particular, are struggling in the popularity stakes. However, the upper echelons in these areas have rarely been troubled with such variations, and a clock like Mr East’s will always have been highly sought after and held its own.

Further justification seems hardly necessary, but one of the joys of clock collecting is that these were useful, functional objects, and they can still serve that purpose if carefully maintained. A clock like the East wall clock, which runs for a week on one winding, should be good for a minute or two in that time, and with its hour striking on the silvery sounding bell, will provide the correct time, visibly and audibly for the entire household.

Dr Helen Jacobsen is the curator of French 18th-century decorative arts at the Wallace Collection in London

Dr Helen Jacobsen is the curator of French 18th-century decorative arts at the Wallace Collection in London

French 18th-century Clock

We are rather spoilt at the Wallace Collection by having an array of stunning French 18th-century clocks, which combine fascinating horology with cases of exquisite design and craftsmanship. One which always makes me smile, however, is a musical clock from the early 1760s, which is a glorious confection of exuberant gilt bronze and rose pink silk.

We are rather spoilt at the Wallace Collection by having an array of stunning French 18th-century clocks, which combine fascinating horology with cases of exquisite design and craftsmanship. One which always makes me smile, however, is a musical clock from the early 1760s, which is a glorious confection of exuberant gilt bronze and rose pink silk.

The case is attributed to Jean-Claude Chambellan Duplessis the Elder. The case was cast and chased by François-René Morlay and the movement is by François Viger.

The carillon is probably not by Viger, but by a specialist maker of musical movements.

The case is flanked by sprays of flowers and leaves and, at the top, perched on a rocky outcrop, a beautifully modelled spaniel peers down as he uses his paws to retrieve a pheasant from beneath an oak branch. Resting on the corners of the base are musical instruments, such as a violin, a tambourine, a French horn and bagpipes, alongside some sheet music and a trumpet with a banner depicting the fleurs-de-lis of France.

The naturalism achieved in the gilt bronze flowers, leaves, twigs and acorns is remarkable and the entire piece conjures up the early autumnal hunting season that played such a large part in the life of the court of Louis XV, who was reputed to have hunted six days a week.

To cap it all, on the hour every hour the carillon plays one of 13 tunes, making a charming reminder of the passing of time. While some people may think the rococo style too ornate, this clock would surely appeal to everyone – especially the dog-lovers among us.

Daniel Clements is the owner of the London-based antique clock shop Pendulum of Mayfair.

Daniel Clements is the owner of the London-based antique clock shop Pendulum of Mayfair.

Bracket Clock

Bracket clocks are universally popular and can grace any mantelpiece. This elegant two-train movement has original verge escapement and an exquisitely engraved backplate. I love the flame mahogany and the ability to turn off the chime if required.

Bracket clocks are universally popular and can grace any mantelpiece. This elegant two-train movement has original verge escapement and an exquisitely engraved backplate. I love the flame mahogany and the ability to turn off the chime if required.

In today’s market the style of the case is very popular as it is simple and elegant, with gracious appeal.

The clock was made c. 1790 at the height of this country’s clock-making prowess. After 1800 we saw a fall off in quality and so this period, for me, represents the summit of engineering and cabinetmaking beauty.

The silvered centre to the dial with calendar hand is surrounded by brass spandrels, and the whole dial is encased in a sublime cabinet of outstanding veneers.

Its maker Robert Wood was a fine London clockmaker.

Tracy Borman is a historian and author, and joint chief curator of Historic Royal Palaces

Tracy Borman is a historian and author, and joint chief curator of Historic Royal Palaces

Hampton Court Clock

The year is 1540. Henry VIII has been on the throne for more than 30 years and has ruled the kingdom with an iron fist.

But his health is declining, thanks to a jousting wound that has turned ulcerated, his enormous weight gain and a range of associated ailments. Desperate for reassurance he will regain his youthful vigour, he turns to astronomy.

In common with most other Tudors, the king firmly believed in the influence of planets over a person’s health, wellbeing and character. He therefore regularly has his horoscope cast – not, as we might today, to find out what events might befall him, but to discover more about his physical wellbeing, and which diseases he might be prone to.

Henry’s horoscopes predicted poor sleeping patterns, a high sex drive, excessive wet dreams, headaches and constipation.

Henry’s horoscopes predicted poor sleeping patterns, a high sex drive, excessive wet dreams, headaches and constipation.

But what has all this got to do with the magnificent clock that sits atop a gatehouse overlooking Clock Court at Hampton Court Palace? Well, Henry’s obsession with astronomy and health was such that in 1540 he commissioned an “astronomical clock” from Nicholas Oursian, a renowned clockmaker of the time.

The Tudor equivalent of an iPad, this remarkably sophisticated piece of technology showed not only the time, but the month, date and number of days since the beginning of the year. Built before Copernicus’s theory about the sun was accepted in England, it has the earth at its centre with the sun revolving around it, while outer dials show the movements of the moon and the number of days since the New Year.

It also charted the movement of the constellations in the Zodiac and, of more immediately practical use to Henry and his courtiers, the time of high water at London Bridge.

OK, so it’s not the sort of thing you could carry in your pocket, but given the chance I’d swap my touch screen for it any day.