The Essential Guide to Military Watches

The boom in demand for military watches continues unabated with none more popular than the highly collectable ‘Dirty Dozen’.

There’s something about military watches. They sell for twice their civilian equivalents and more and more of us, from youngsters to women, are getting in on the act. None are more iconic than the ‘Dirty Dozen’ – the 12 Swiss-made military watches commissioned by the British MoD towards the end of WWII.

While prices are on the rise, they are still an affordable purchase for many vintage watch collectors and wearers. Add to this the romance that comes with a military watch that played a starring role in a period of history and you have a timepiece with an unrivalled integrity.

Military Watches – A Brief History

Wristwatches were military timepieces before they were anything at all – at least for men. The event that propelled them from pocket to wrist was WWI.

In the trenches soldiers fashioned metal loops onto their pocket watches and mounted them on their wrists, as a more convenient way of checking the time when carrying a rifle.

The look stuck, but it wasn’t until WWII that they became more widely taken up and, even then, weren’t universal. From the 1890s until the end of his life Churchill carried his father’s gold Breguet pocket watch, nicknamed The Turnip.

But seeing heroic pilots and servicemen returning with their bomber jackets and standard issue wristwatches did wonders for the design.

It was only towards the end of WWII, around 1945, that the ‘Dirty Dozen’ came into being. Prior to that, the war was fought using the more humble “ATP” or Army Time Piece watch.

Swiss Supermacy in Military Watches

With British watch manufacturers employed making naval and aviation instruments, Switzerland’s neutrality allowed its watch makers to reign supreme.

As with their successors the ‘Dirty Dozen’, there were 17 Swiss makers employed to make the ATPs: Buren, Cortebert, Cyma, Ebel, Enicar, Eterna, Font, Grana, Lemania, Leonidas, Moeris, Reconvillier, Record, Revue, Rotary, Timor, and Unitas.

Ebel, Revue and Timor also produced two types of watch so, in all, 20 watch types were responsible for the ATP series. The makers also supplied near identical models to Germany, Italy and Japan.

While these watches complied to some specific standards in relation to, for example, night time visibility, the majority were similar to equivalent civilian models. Most of the cases of ATP watches were made out of chrome-plated brass, although some were made from steel. The movements were manual wind, and had 15 jewels.

The Dirty Dozen Military Watches

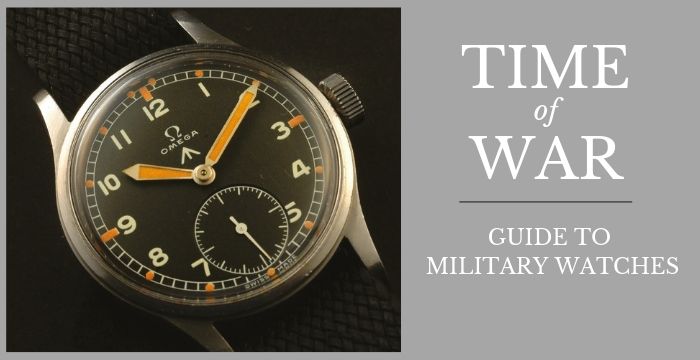

In 1943, the MoD saw the importance of having a general-use timepiece for the armed forces. The specification demanded that they should be reliable, waterproof and shockproof. The watches would have a black dial, Arabic numerals, luminous hour and minute hands, luminous hour markers, a railroad minute track, shatterproof crystal and a stainless-steel case.

Their power would come from a 15-jewel manual hand-wound movement.

Swiss makers

12 Swiss manufacturers were found to fit the specific brief: Buren, Cyma, Eterna, Grana, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Lemania, Longines, IWC, Omega, Record, Timor, and Vertex. Of these, Vertex was the only British brand, but it also had factories in Switzerland.

Each carried a case-back engraving of WWW, standing for ‘Wrist. Watch. Waterproof’, and the broad arrow symbol on the dial, showing they were property of the Crown.

Some 145,000 of these were made, although not in equal numbers. Omega made 25,000 and little-known Grana is thought to have made fewer than 1,500.

Two serial numbers were required, one being the manufacturer’s number, and the other (with the letter) being the military store number.

Numbers of Dirty Dozen watches

WWWs are by no means rare, as rough estimates say that around 145,000 of these were produced and delivered in 1945, but each company produced a different number (from 25,000 to less than 1,500), which explains why it is so hard for collectors to complete the set.

On top of that, it is believed that a lot of these WWWs were destroyed in the 1970s due to the presence of radioactive Radium-226, in the luminescent material.

While watch collectors praise the movement of the IWC, because of its rarity, it is the Grana that is the most coveted and expensive of the ‘Dirty Dozen’ and the one most often missing from a collection.

Individually these watches may not be as desirable as other vintage chronographs but, to those who are collecting a whole set, they are highly prized. Other collectors opt for the Longines which, at 37.5mm, suits today’s market.

After the War

Because the watches were only delivered towards the tail end of WWII, Britain was left with a significant surplus when the war ended.

While conflict had finished in the West, the Dutch Army (or K.N.I.L. Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger) was fighting Indonesian freedom fighters after they declared independence. With a need for military goods, Britain waded in to provide military watches to the Dutch army – hence WWW were reissued K.N.I.L. case backs – now some of the rarest WWW watches.

Then these reissued WWWs were re-reissued again to the A.D.R.I. (Army of the Republic of Indonesia). In some cases K.N.I.L. has been scratched off the case back with A.D.R.I. engraved.

How much do Dirty Dozen watches cost?

In comparison with other chronographs, the ‘Dirty Dozen’ watches are relatively affordable and, while examples by the rarer and bigger name manufacturers will set you back around £1,500 and upwards, the less well-known brands such as Timor, Eterna or Buren can be picked up for £500-£1,000.

However, prices are on the rise for these lesser brands as the market increases. Expect to pay £10,000 to £15,000 for the rarer Grana.

Market for Military Watches

Halls’ watch specialist Jack Austerberry assesses the market for military watches

What is it we love about military watches?

Over the last decade, the watch market has seen a resurgence in demand for honest, original watches, with genuine patina. I think what we all love about these low production military watches is that they have a story behind them, and in a modern world where “luxury” watches are produced in their millions every year, provenance has become imperative.

How often do watches from the ‘Dirty Dozen’ appear at auction?

While these watches may be difficult to find in good overall condition, there has been a small influx into a number of auction houses across the country. I have been lucky enough to consign three ‘Dirty Dozen’ pieces which sold in our June sale.

Are they attracting a new collector base?

Good question. I think if you’d have asked the same question 10 years ago, the general consensus would have been that only seasoned collectors with a preferred niche would have been the buyers. But I’ve noticed that market trends are being influenced by social media, as well as horological information and research available online. As a result, I think the collectors’ market as a whole is becoming more youthful as every year passes. Men and women of all ages are getting involved in collecting watches; from 19th-century Breguets, to the futuristic looking MB&Fs. It’s an exciting time to be working in the industry.

Are there any overlooked areas of military watch collecting?

In my opinion, British military-issued CWC (Cabot Watch Company) wristwatches of the 1970s are highly underrated, being well built, simple and mechanical, I’ll leave it up to the market to decide if these will be the next watches to skyrocket. I don’t think it can be understated how important it is to buy something that you like, and in the best condition available.

Have you got a favourite military watch?

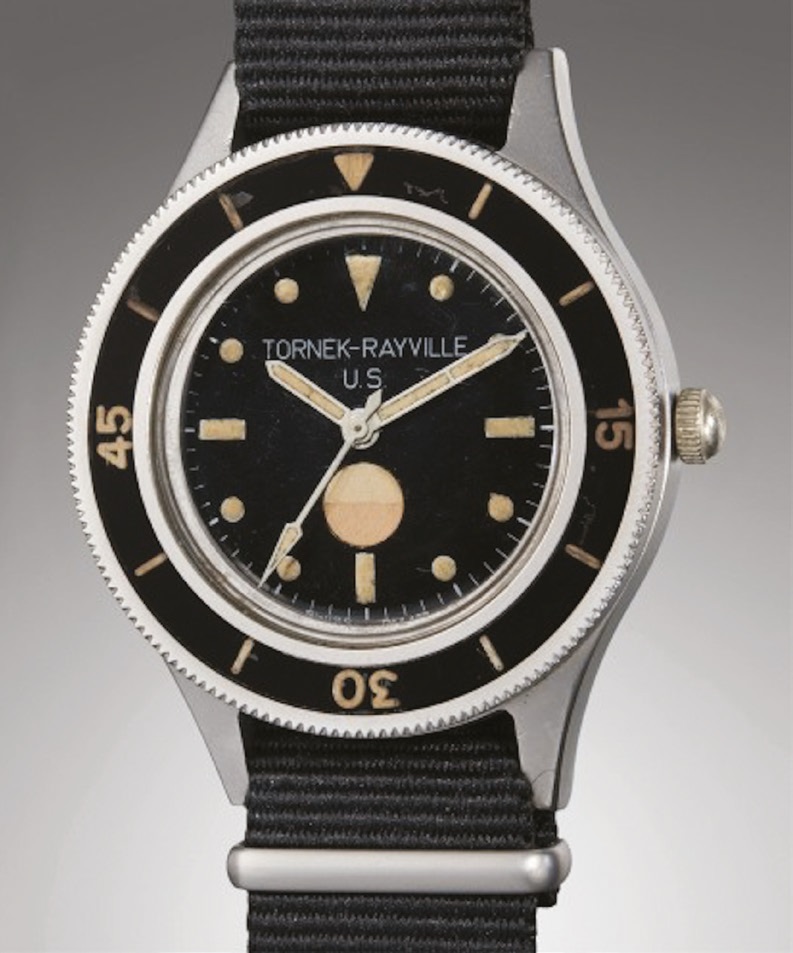

Yes, the Tornek-Rayville TR-900. Unfortunately, many of these US military watches were buried in concrete barrels due to the high levels of radiation emitted by the luminous compound applied to the dial. It’s estimated that between 30 and 50 examples survive of the (approximately) 1,000 originally manufactured. As a result, and to my dismay, they regularly exceed the $100,000

mark at auction.