The ‘Four Ages of Wood’ – David Harvey

Antiques expert and Antique Collecting magazine columnist, David Harvey, considers why the ‘four ages of wood’ might not be as clear cut as previously thought

While carrying out some research on a newly-acquired piece, I came across Percy Macquoid’s wonderful books on 17th to 19th-century English furniture, published in the early 1900s.

Macquoid divided the centuries into four distinct ages: oak, walnut, mahogany and satinwood. This may well have been appropriate at the time Macquoid wrote his book, but since then knowledge on the subject has improved beyond all recognition. So much so, in fact, I am reminded of a wonderful quotation from Mark Twain: “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

The refectory table (above) dates from the 17th century but, if we compare the legs to the turnings guide in Victor Chinnery’s book (Oak Furniture, The British Tradition, 1979), the “rising baluster” is dated anywhere between 1580 and 1800.

There never was a cut-off date when one timber gave way to another. Indeed, oak has been the mainstay of vernacular furniture throughout our history.

Age of Walnut

The second half of the 17th century saw the move from joinery to cabinetmaking, with the Restoration seeing a number of continental furniture makers coming to the UK, working at the Williamite court. The rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London in 1666 also presented opportunities for foreign cabinetmakers, stonemasons, carvers, gilders and a host of other disciplines, many of whom settled in the vicinity of the great cathedral.

Royal taste for veneered and inlaid furniture was soon being copied by courtiers and others wanting to reflect the latest fashions and so the ‘age of walnut’ came into being with proponents such as the royal cabinetmaker Gerrit Jensen (1634-1715). Such makers perfected the art of oyster veneering using consecutive cuts of veneer from branches to produce much sought-after patterns in walnut, laburnum and, on rare occasions, the expensive ‘princes’ wood, also known as kingwood (see above). These styles continued well into the 18th century and the reigns of Queen Anne and George I.

Burr Walnut

Using timbers’ natural figuring continued unabated into the 18th century with stunning results, such as in this architecturally-inspired bureau bookcase in burr walnut.

The fall and all the drawers are “quartered” across to produce a strong pattern, while bun feet were still very much a feature at this time. There are a number of explanations as to the demise of walnut in cabinetmaking during the 18th century, one of which is that the great storm of 1703 destroyed much of our native walnut, along with a French embargo on the exportation of European walnut to the UK as they were fearful of it being used to build warships. Just imagine a naval vessel of that period with a burr walnut dashboard!

Move to Mahogany

While mahogany was used for shipbuilding by the Spanish as early as the 16th century, and samples were bought back from Trinidad by Sir Walter Raleigh for approval by Queen Elizabeth I, it didn’t find favour among cabinetmakers until the 1720s. (Although it continued to supplant oak as the mainstay for shipbuilding in the UK as it was less likely to suffer damage or splinter from gun and cannon shot.)

The earliest example of mahogany furniture used the straight-grained and dense timbers from the Caribbean.

As time went on so the cabinetmakers and furniture designers became bolder and, as we move from the Palladian era into the Rococo styles of the mid-18th century, numerous French designs and iconic elements appeared on English furniture.

A good example of the anglicisation of a continental design is the serpentine commode (above) made almost certainly in London during the middle years of the century, and there isn’t a straight edge on this anywhere.

Thomas Chippendale

The 18th century brought neo-classicism, with Robert Adam and Thomas Chippendale designing and making pieces with the increasingly-fashionable satinwood.

As Britain widened its global trade it imported an ever greater number of goods to meet a rapidly-expanding market, hence more exotic timbers from far flung areas became more readily available. Macquoid encapsulated this in his ‘age of satinwood’ from the last decades of the 18th century.

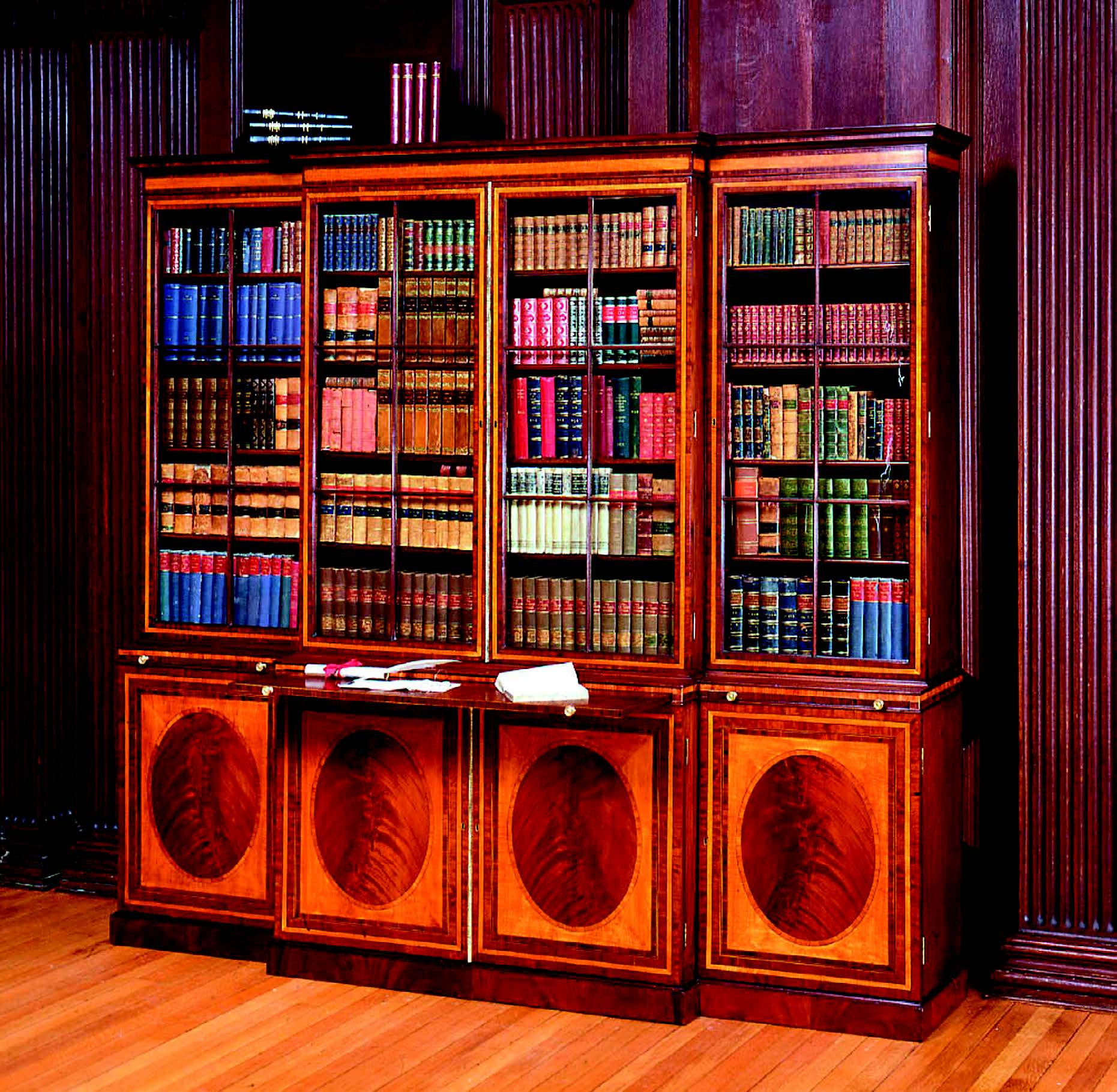

It also became fashionable to use satinwood as an inlay or banding in conjunction with other woods. An example of this is the mahogany breakfront bookcase with satinwood panels set in bandings of kingwood (princes wood) and tulipwood, with ebony and boxwood stringing.

Interestingly, it was made in 11 pieces and cased for ease of transportation, possibly from Gillows of Lancaster, to its home where it would have then been assembled on site by a Gillows’ team.

Exquisite Work

Satinwood was seldom used in the solid, as the most attractive veneers could be cut from larger pieces making it a much more commercial enterprise having been imported at great cost.

Both the bookcase and this Pembroke table date from the 1780s and help to illustrate the variety of designs and competence of the extraordinary cabinetmakers of the day.

During the last quarter of the 18th, and the first of the 19th century, we see a definite lightening of the form for furniture with pattern books being widely published by many who have become household names. Some, such as Hepplewhite and Sheraton, have even given their names to styles which continued into the Regency period.

David Harvey is the owner of W R Harvey & Co. Ltd., located at 86 Corn St, Witney, Oxfordshire. For more details go to www.wrharvey.com