Visiting Charleston – rural home of the Bloomsbury Group

With its bucolic setting in the rolling heart of the South Downs, where tumbledown barns sit amid the colour of a fecund English garden, Richard Ginger explores why Charleston Farmhouse was such a rural haven for the Bloomsbury Group in the early 20th century – evoking comparisons with Monet’s home in Giverny

It was Leonard and Virginia Woolf who first discovered the property which, on the downs by Firle Beacon, was close to their own Sussex house. She introduced it to her artist sister, Vanessa Bell (1879-1961), her husband Clive Bell (1881-1964) and her lover, the artist Duncan Grant (1885-1978) with Bell signing the lease in 1916.

Before long all three were regular visitors, along along with the couple’s two young children (Julian and Quentin) as well as the daughter Angelica which Bell and Grant had together.

This unconventional and creative coterie quickly welcomed other leading lights of the Bloomsbury Group to the new home for extended periods, with visitors including the art historian and critic, Roger Fry; influential economist, John Maynard Keynes and the writer and critic, Lytton Strachey (Grant’s former lover).

The writer and political theorist, Leonard Woolf; Thoby Stephens (Vanessa and Virginia’s brother) and Russian ballerina, Lydia Lopokova (Keynes’ wife) also stayed at the farmhouse.

Bell enthused about her new home in a letter to Fry. She wrote: “The pond is most beautiful with a willow at one side & a stone – or flint – wall edging it all round the garden part, & a little lawn sloping down to it, with formal bushes on it. Then there’s a small orchard & the walled garden…& another lawn or bit of field railed in beyond.

Love Life

Away from the confines of the capital, this artistic diaspora quickly turned the somewhat stolid and square farmhouse into a hub of creativity and a setting for alternative ways of living. As famously noted by the American satirist Dorothy Parker: “They lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles.”

Bell’s painting, The Pond, 1916, was, according to Grant, her first painting produced at Charleston and featured one of the main reasons she decided to move to the farmhouse. Grant’s own work The Hammock, Charleston (c. 1921-1922) shows Bell, her three young children and their tutor lounging on a summer’s day.

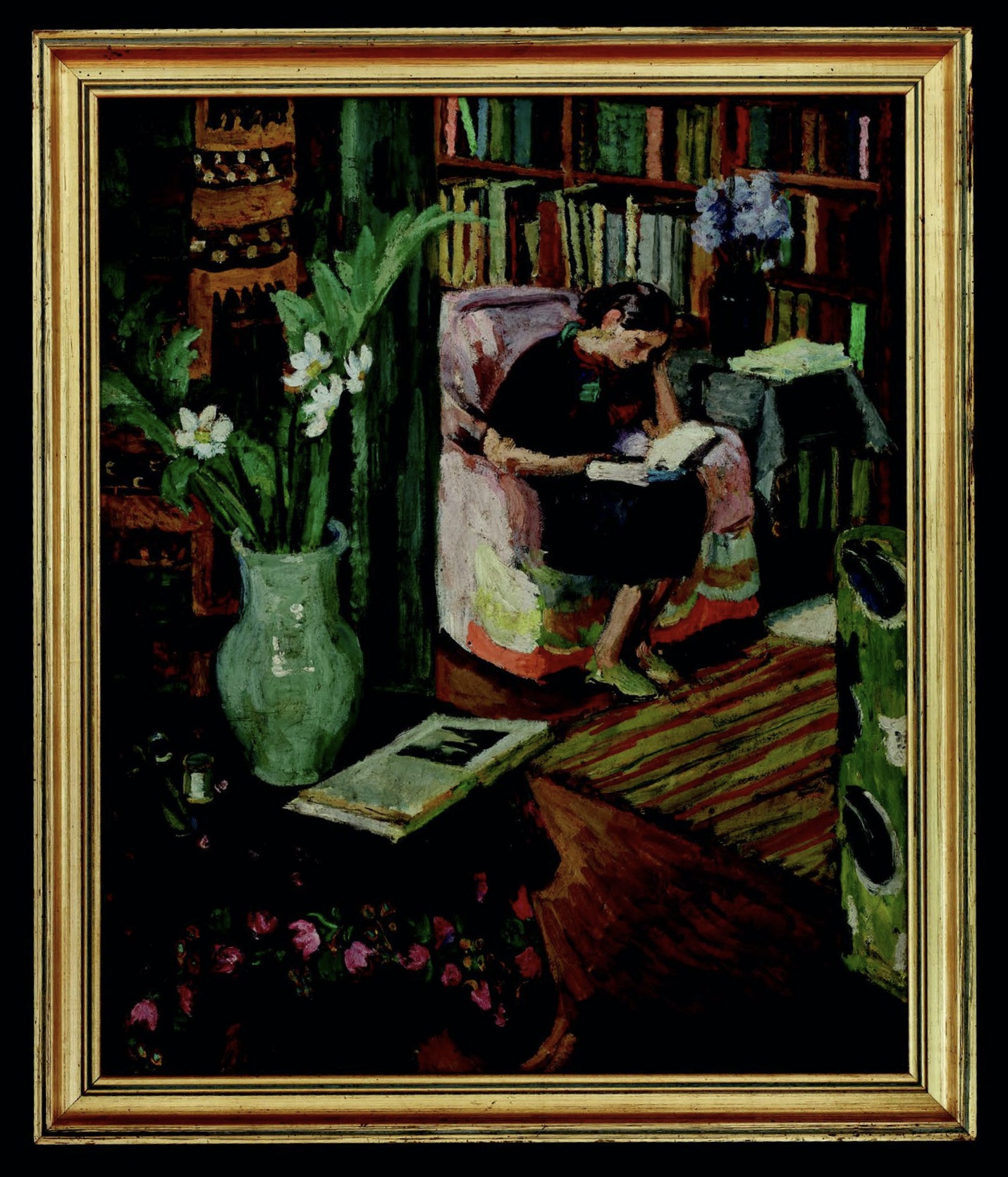

Two other notable family portraits feature Grant’s 1930 portrait of Julian Bell, his lover’s son who died seven years later in the Spanish Civil War aged just 29. The second is Vanessa Bell’s own work of her 18-year-old daughter Angelica in a book-filled interior. The tender moment pre-dates Angelica’s discovery she was, in fact, Grant’s not Clive Bell’s daughter, a revelation which caused a rift in the family.

Domestic Inspiration

Both Bell and Grant took inspiration from everything from food preparation in the kitchen, to portraits of the household cat, Opussyquinusque.

Even the oak-panelled walls and furniture of the building became playful canvasses for expression, resulting in a carnival of beautifully-patterned surfaces, murals and motifs throughout the house.

Fabrics and ceramics designed by Bell for the Omega Workshops, principally started by Roger Fry in July 1913, adorned the interiors.

World at War

However, in 1916, war was raging in Europe and any idyll was shattered by the call-up for men under 40 to enlist. It was a political climate entirely at odds with the group’s anti-war and pacifistic stance – many were conscientious objectors – and in order to avoid the draft, Bell secured work on a local farm for both her husband and Grant. As a reserved occupation, it avoided the chance of enlistment or possible imprisonment.

Charleston continued to provide the perfect surroundings to redefine the era’s artistic boundaries while exploring the European modernist movement. Bell and Grant embraced elements of the contemporary avant garde including cubism and abstract art, producing work that reduced form into geometric shapes, often outlined with black lines. Landscapes became more brutalist and sharply angular, with bold colours.

As the century progressed with travel restricted, amid two world wars, Charleston’s inhabitants and visitors turned to local scenes, such as Bell’s The Barn at Charleston, Winter (c.1940-1941) and Grant’s The Pond in Winter at Charleston (c. 1943).

When not painting family, friends or the surrounding countryside, Bell and Grant would turn to capturing the flowers that grew around them, alongside other curiosities within the house. Bell’s Apples and Vinegar Bottle (1937) is one such example and includes a colourful ceramic bottle purchased by her on a summer trip to Italy. Bell continued to live part of each year at the property, now run by the Charleston Trust, until her death in 1961, while Grant stayed on for longer, until the house became too large for him.