Guide to post-war British silver

Not since Georgian times has Britain been home to the silversmithing tradition it has today. Collector and expert John Andrew reveals the stars of post-war British silver design

It may be our best-kept secret. Since WWII, British smiths have been creating silver objects at the highest level, combining exceptional craftsmanship with an extraordinary standard of design.

In some ways it is no surprise. From the medieval period through to rococo and neoclassicism, the history of silver production in England is a long and rich one, with its hallmarking system the oldest form of consumer protection in the world.

However, a new generation of designers came to prominence in the post-war era to effectively reinvent the output of silver in response to changing markets.

These craftsmen and women made a profound and lasting impact on the direction of modern silver and ushered in a new ‘golden age’ for British silver.

Many collectors still ignore this recent work but, with a growing market and new admirers, the best work from the 1960s and 1970s is becoming more popular, as is the work of contemporary makers.

Such is the reputation of the country for silver design that it is now attracting overseas students to study here, while established silversmiths from the Far East, Continental Europe, Scandinavia and elsewhere have settled in the UK to practise their craft. The Goldsmiths’ Fair, which took place in September, featured 136, silver and goldsmiths and gave collectors the opportunity to meet the men and women behind this staggering revolution and directly purchase pieces from the makers destined to be the antiques of the future.

Post-war origins

To understand the origins of this tsunami of talent, we have to go back to WWII, and even further. Before hostilities ceased, the government realised it would need exports to generate cash to pay off the nation’s debts. While British craftsmanship and materials were fine, design was lacking. There was a need for consumer durables that were both modern and aesthetically pleasing for overseas buyers.

The Council of Industrial Design (CoID) was formed for this purpose. The Royal College of Art (RCA) was also recognised as another vehicle to help achieve the government’s goal by producing industrial designers.

In the first half of the 1950s, the school was blessed in having three talented silversmiths as students: David Mellor (1930-2009), Robert Welch (1929-2000) and Gerald Benney (1930-2008).

All three went on to design and make silver professionally, though not necessarily for the entire period of their career. Each also became an industrial designer and all three saw the businesses that they established being continued by a son.

British silver stars

The RCA’s triumvirate graduated in 1954-1955. Mellor was immediately appointed design consultant to Walker & Hall of Sheffield and his Pride range began to be produced. He established his own studio-workshop nearby and over a long career designed everything from silver to traffic lights. After he became a cutlery manufacturer as well as a designer, he became known as the “Cutlery King”.

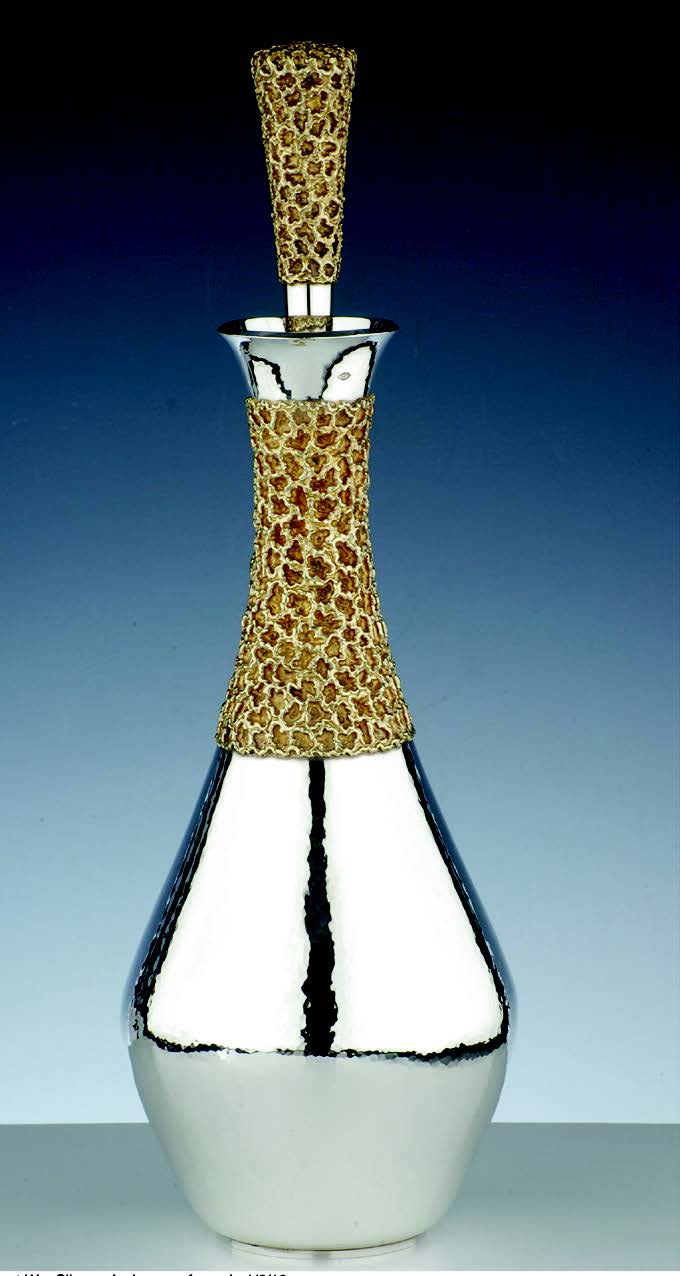

Gerald Benney established his studio and workshop in central London. In addition to his silversmithing business, he was initially involved in designing a range of products from clocks to prams. By the late 1950s, Benney’s commercial work was losing its Scandinavian influence. Another step change occurred in 1961 when texturing became a feature of his work. It was quite accidental. While hand-raising the bowl of a goblet he inadvertently used a hammer with a damaged head. After half a dozen blows, what should have been a smooth surface had a bark effect pattern imposed on the silver.

Robert Welch was the last to graduate in 1955. He became a design consultant to the stainless steel manufacturers Old Hall and established a design studio and silver workshop at Chipping Camden. Although Welch has long been associated with cutlery, the repertoire of his designs ranged from clocks to lighting, glassware to kitchen tools. Welch continued designing silver until the end of the 20th century. Robert Welch Designs Limited continues to sell small pieces of silver.

Stuart Devlin (1931-2018)

In 1965, Mellor, Welch and Benney were joined by the Australian designer, Stuart Devlin, when he decided to open a workshop in the capital. Devlin had trained as an art teacher in his native Australia before studying gold and silversmithing in Melbourne and later at London’s Royal College of Art. He followed this by spending two years at Colombia University where he developed a career as a sculptor.

Back home, as agreed, he returned to his role as an educationalist, while designing the coins for the Australian decimal coinage.

At the age of 32, during a visit to London to supervise the cutting of the dies for the new coins, the seeds were sown for establishing himself as a silversmith in the capital.

His exploration of sculpture in America gave him the skills of working with molten metal, allowing him to adapt and refine techniques to produce a wide variety of textures on the surface of silver as well as making filigree forms. The result was silver, the likes of which had never been seen before.

British silver in the ‘70s

A number of expert silversmiths continued to expand and refine the craft in the 1970s, creating world-beating designs.

Michael Bolton (1938-2005)

One such was the self-taught Hammersmith-born Michael Bolton (1938-2005) who was among the top dozen or so designer craftsmen working in silver in the years from 1970.

His wasn’t an easy start. Unable to find a place at art college, he embarked on a career in commerce, first as a clerk in a shipping company and then with American Express, which offered him a £350 “golden handshake” in 1968. He took it and set up a pottery studio at his home at Biggin Hill.

Between 1975 and 1981 Bolton exhibited at the Goldsmith’s Company Loot exhibitions. In the catalogue of the 1996 Contemporary Silver Tableware exhibition he said his work was: “…inspired by the magic and aura of Celtic, Roman and Anglo-Saxon metalwork, the romanticism of the King Arthur legends, and the ethics and ideology of the late 19th and early 20th-century British arts and crafts movement.”

Malcolm Appleby (B. 1946)

Born in Kent, Appleby trained at the Central School of Art before moving on to the Sir John Cass School of Art, Architecture and Design and the RCA before setting up a workshop in Grandtully, Perthshire, in 1970. Since then, Appleby has spent the majority of his working life in Scotland taking inspiration from nature.

Over his career, Appleby developed new techniques for engraving with some of his early work including the engraving of the gold coronet made for the Prince of Wales’ investiture (designed by the goldsmith and artist Louis Osman) in 1969. With work on show at 10 Downing Street as well as a number of major museums, Appleby is considered to be among the finest craftsmen working today. He was awarded the MBE in the 2014 New Year Honours for his engraving skills.

Graham Stewart (1955-2020)

The Scottish-born designer, gold and silversmith Graham Stewart, who died in 2020, ran a workshop and gallery in Dunblane from 1978. While specialising in fine hand-cut engraving, the silver he produced used traditional techniques such as raising, spinning, cold forging, planishing and chasing.

Collecting post-war British silver

John Andrew explains the extraordinary rise in value of post-war silver created in Great Britain

The market for silver is nothing like it was. In days of old the well-heeled had dining tables that groaned under the weight of silver with an army of servants to polish it. The aspiring middle classes had objects plated with a very thin layer of silver as opposed to solid pieces (EPNS – electroplated nickel silver), but nevertheless employed people to keep it sparkling.

I am a baby boomer, born in 1951. There was no christening silver for me, just an EPNS serviette ring from my godmother. These were the years of postwar austerity, when my parents celebrated their silver wedding anniversary in 1967, all they wanted was stainless steel – far easier to look after in an age when full-time domestic help was no longer the norm.

Fall and rise

The late 1960s saw a boom in antique silver – a standard Georgian coffee pot would sell for £2,000, equivalent to £35,000 today. However, in 2021 the same pot would knock down for about £1,000-£1,500.

On the other hand, in July a three-piece coffee set dated 1976 by Gerald Benney (1930-2008) weighing 53.0oz, sold at Woolley & Wallis for £8,000 hammer.

In January 2003, I bought a 1986 Benney five-piece coffee set (with sugar spoon and tray) weighing 81oz for an all-in price of £2,746.51. At the time of purchase pure silver bullion was just over £3 per troy ounce – at the end of July 2021, it was just over £18.

While pieces by the better-known makers, such as Benney and Devlin have leapt, work by lesser-known but notable names can still be had for a song.

Contemporary silver is offered at auction by the smiths themselves; would-be collectors can research what is on offer on the website of Contemporary British Silversmiths, which also has an online shop (www.contemporarybritishsilversmiths.org).

Contemporary silver is offered at auction by the smiths themselves; would-be collectors can research what is on offer on the website of Contemporary British Silversmiths, which also has an online shop (www.contemporarybritishsilversmiths.org).

The UK has a raft of talent resulting in a wide range of hand-crafted contemporary silver. In addition to buying what will become antiques of the future, it is fascinating to talk to smiths about their work, as well as handling contemporary items of beauty. This month’s Goldsmith’s Fair provides the ideal platform.

This wonderful craft will only survive if there are buyers to support it.

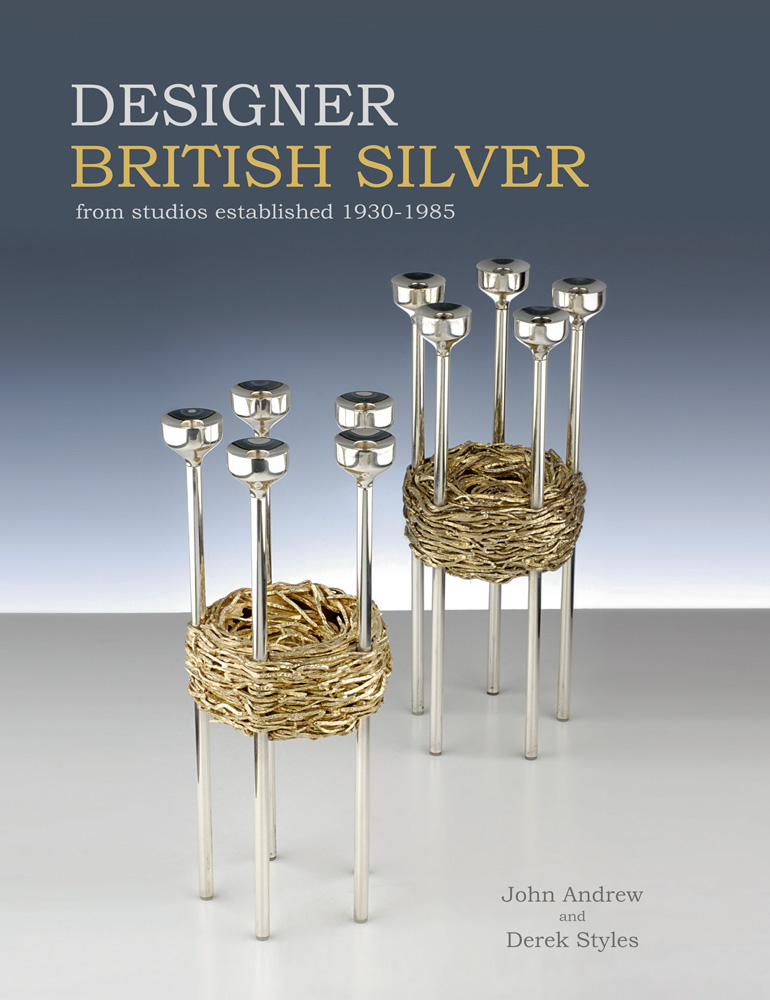

John Andrew and Derek Styles’ book Designer British Silver, is available from ACC Art Books, priced £75.