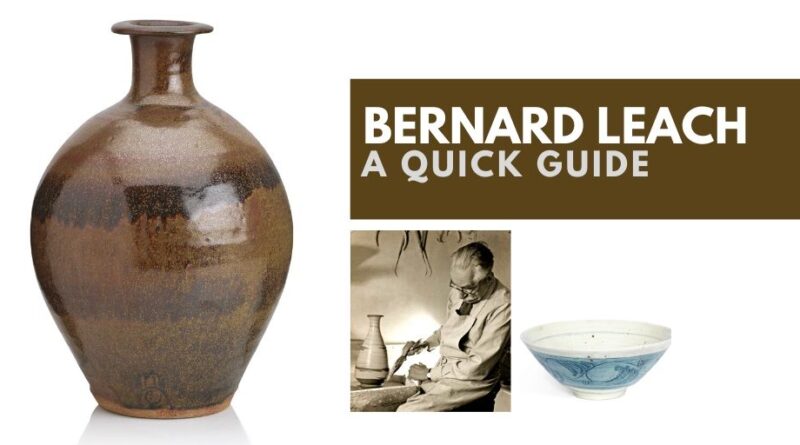

Bernard Leach – a quick guide to his ceramics

On the centenary of the influential Leach Pottery formed in St Ives in 1920, Antique Collecting highlights the ceramics of its founders Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada.

Regarded as the ‘father of British studio pottery’, Bernard Leach’s contribution as both a ceramicist and teacher is difficult to over-emphasize.

Life of Bernard Leach

The Leach Pottery, established in 1920 with his friend, colleague and fellow artist Shoji Hamada, went on to become one of the most influential studios of the 20th century.

Funded by the Guild of Handicraft, Leach and Hamada wanted to challenge the homogeneity of British mass production and position ceramic practice as an equal to the fine arts. Not only did the potters construct the first Japanese-style climbing kiln in the West, their subsequent influence on studio pottery and the philosophy of ceramics became internationally renowned.

Leach’s influence and ideals were to resonate strongly within the community of modern artists living in post-war St Ives.

Bernard Leach – the early days

Bernard Howell Leach was born in Hong Kong in 1887, the son of English parents. His mother died in childbirth and he was taken to Kyoto in Japan by his maternal grandparents. Four years later his father remarried and he brought Leach back to Hong Kong and then on to Singapore when he was appointed a judge.

He returned to England aged 10, leaving school at 16 having excelled only in drawing, elocution and cricket. Leach then enrolled at The Slade School of Art but left when his father became ill in 1904 to seek out a job in the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC).

When his father died, with a small inheritance, the 21-year-old enrolled at the London School of Art in Kensington where he was taught etching by Frank Brangwyn who was an inspiration to Leach.

Return to Japan

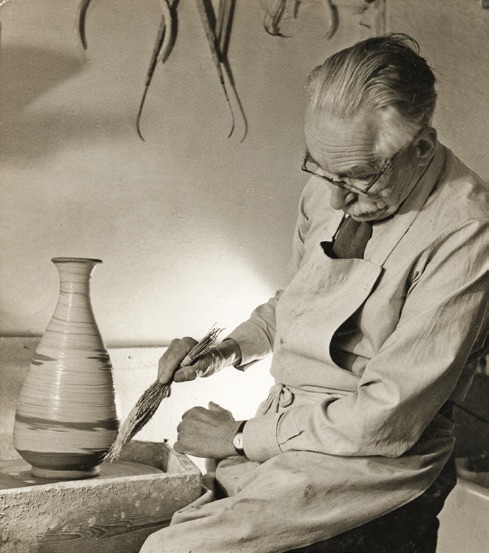

It was on his return to Japan in 1909 that he first discovered ‘raku’ (a low-fired earthenware that was an integral part of the culture of the Japanese tea ceremony). At a party in Tokyo, he was invited to decorate such a piece which had been recently fired and glazed.

He was enthralled by the firing process and wrote, “By this to me a miracle, I was carried away to a new world. Enthralled, I was on the spot seized with the desire to take up the craft”. This was a pivotal time in Leach’s life and he decided to follow the path of ceramics.

He was recommended and then studied with Urano Shigekichi, known by his title of Kenzan VI, two days a week for two years. It was a remarkable pupillage, with Leach becoming the first Western potter to be trained in the Oriental tradition.

This cultural cross-pollination of East and West was important in the development of Leach’s art, both in the type of kiln he set up and the pottery he founded in Cornwall with Shoji Hamada. Potter and author Edmund De Waal described him as ‘a kind of link or courier between English and Japanese potters in the interchange between our pre-industrial tradition and theirs.’

Like William Morris before him, Leach was concerned with the dying folk arts of Japan and England that were gradually being eroded by the modernising forces of the 20th century. He and Hamada felt that is was their duty to revive these crafts before they were lost to the course of history. His exposure in Japan to ceramics produced there, and in Korea and China, was a great source of inspiration, as was the English slipware tradition that was still being practised in small pockets of Devon.

Bernard Leach in St Ives

Leach returned to England in 1920 with Shoji Hamada. Hamada was a young, enthusiastic student at the Kyoto Institute of Ceramics, who had followed and admired both Leach’s and his fellow artist Kenkichi Tomimoto’s works in various exhibitions in Tokyo.

It was through these exhibitions that he eventually got to know Leach and became so excited by his ideology and lifestyle that he volunteered to accompany the artist to the UK as his assistant.

Hamada’s detailed study of glazes was considered to be of great value to Leach, who had not been educated in these techniques.

They settled in St Ives in Cornwall, a small artistic community, where they set up a business. Leach purchased a small strip of land and, using local workmen, built a kiln, house and studio. He continued to experiment with many forms and techniques even holding raku parties at which his first wife Muriel served Cornish teas for 1 shilling.

By living in Cornwall Leach gradually absorbed aspects of Celtic mythology and recreated them by featuring mythological creatures and heraldic images in many of his works. Similarly, the shapes he used were inspired by the English rural tradition with an emphasis on medieval jugs, mead jars, grain jars and flagons. He began to study and reinterpret the signed pieces of 17th-century slipware by Thomas and Ralph Toft. This allowed him to play with the idea of his identity as a potter, believing all pots were a projection of the minds of their creators.

This is evident in many of his pieces where he incorporated his monogram and the St Ives pottery seal with the context of his designs. In expressing himself in such a way he found satisfaction through what he perceived as the balance between pot and maker and beauty and function.

This sense of harmony, which he learnt in the East and which he felt was lacking in the West, is obvious in his art forms. The influence of the East is also evident in other ways, from the use of the simple shapes inspired by the Japanese tea ceremony, the yunomis (Oriental teabowls), saki bottles, teapots and fl asks to his interpretation of the glazes from the Sung dynasty (oatmeal, tenmoku, celadon).

His repeated use of ‘graphic’ images such as the willow, the pagoda and the mountain range, created through simple brush strokes, is also straight from Japanese culture.

Bernard Leach’s Legacy

Leach’s training of aspiring students was formidable in guiding and inspiring a generation of artists.

Michael Cardew (1901-1983) became the first student at the Leach Pottery in St Ives in 1923, where he worked for three years. He established his pottery, Winchcombe Pottery in Gloucestershire in 1926, where he concentrated on making slip-decorated earthenware, creating traditional and affordable domestic pieces with increasing success.

Richard Batterham (b. 1936) trained at the Leach Pottery in 1957 and 1958, returning to his native Dorset in 1959 to set up his own pottery.

Norah Braden (1901-2001) studied at the Royal College of Art until 1925 when she joined the workshop. Leach described her as one of his most gifted pupils and her work was equally appreciated by Michael Cardew. In 1928 she joined Katharine Pleydell- Bouverie (1895-1985) at her pottery in Coleshill, where she spent the next eight years producing individual pieces and undertaking extensive glaze experiments using ash glazes made from the plants and wood on the estate.

Although distinct potters in their own right, Leach’s influence on his own family – among others Janet, David (his son) and John (his grandson) – is also of note.

On Leach’s death in 1979 production at the pottery continued where it does to this day, with ceramicists remaining true to the Leach ideals and some even producing wares using the original tools dating back to the 1930s.

Did you know?

In the early 1980s, inmates of Featherstone Prison near Wolverhampton used their pottery classes to produce copies of Leach’s work using the prison’s kilns. While many experts were fooled by the fakes, Janet Leach revealed their flaws.

The Market for Bernard Leach

The market for studio ceramics is currently polarised with a few potters attracting a premium at auction.

The market for Leach’s work is strong, with interest on an international level but particularly in Britain, America and Japan (where they consider him one of their own).

Early slipware pieces and academic pieces are highly sought after, with prices further increased by examples decorated with ‘classical’ Leach images, such as the leaping hare, the deer, the salmon and the pagoda.

One of his most famous examples, his ‘pilgrim’ plate produced in the mid-1960s, featured a stencilled motif of a hooded pilgrim with a staff walking towards a mountain range and is in glazed tenmoku.

As collectors become priced out of the top end of the market other collecting trends emerge. Tiles provide an alternative affordable area, particularly those featuring Leach’s best-known symbols. They were a perfect medium for the potter – easy to manufacture, quick to decorate and the flat surfaces ideally suited to Leach’s style of brushwork.

David Leach

David (British, 1911-2005) joined his father’s pottery at St Ives in 1930 as an apprentice.

From 1934-1936 he attended the Pottery Managers course at North Staffordshire Technical College, Stoke-on-Trent to acquire more technical knowledge on pottery.

On his return to the Leach Pottery in 1946 David and Bernard formed a partnership and his industrial training allowed him to modernise the workshop, introducing machinery and developing a new stoneware body. His developments allowed for successful production of the standard ware range, which he designed together with Bernard.

In 1956 he established his own studio at Lowerdown Pottery, South Devon where he developed his individual style, moving away from repetitive domestic ware to make more individual pieces. He was chairman of the Craft Potters’ Association of Great Britain in 1967 and exhibited widely in the UK, Europe and America.

Janet Leach

Janet Leach, nee Darnell, was born in Texas, USA (1918-1997). Before meeting Bernard Leach she was an established artist in her own right specialising in stoneware and porcelain pots with minimal decoration.

In 1938 she enrolled in sculpture classes in New York and worked as a sculptor’s assistant on the Federal Art Project and for Robert Cronback on architectural commissions.

During the war she worked as a welder on ships on Staten Island (1939-1945).

Her interest in pottery began in 1947 and she trained at Inwood Pottery and Alfred University, USA.

She met Bernard Leach, Soetsu Yanagi and Shoji Hamada at Black Mountain College, when they were touring in America in 1952. She soon became interested in Japanese techniques and the philosophy of pottery.

She went to Japan in 1954 where she spent two years studying under Hamada, who she always considered her principal mentor. She was the first foreign woman to study pottery in Japan and only the second westerner.

In 1956, she settled in Britain after her marriage to Bernard Leach and together they ran the Leach Pottery in St. Ives. After her husband died in 1979, Janet continued potting, throwing individual pieces in a variety of clays using a number of different firing techniques. She exhibited widely and held regular one-person shows in England and Japan. Her work can be found in many public collections.