Spode – A Collecting Guide

Spode – the inventor of transfer ware – celebrates its 250th anniversary this year with the popularity of ‘granny’ ware receiving a surprising shot in the arm, writes Duncan Phillips

Go to any antiques market, fair or auction and I defy you not to find at least one large blue and white dinner plate or meat dish with either an Italian blue and white scene or willow pattern Chinese garden. They are the most popular pieces of domestic porcelain in the history of the ceramics industry in Britain.

Furthermore, the fortunes of ‘granny’ ware has recently taken another upturn in popularity due to the most unlikely reason (for those over the age of 30). Brightly coloured tableware looks good on the social media platform Instagram and is, therefore, much sought after by the next generation of collectors.

Long gone are the monochrome table sets from fashionable eateries, as they are replaced with mis-matched vintage styles.

History of Spode

Like most of our major porcelain factories, Spode was started by one man, Josiah Spode (1733-1797).

While Josiah Wedgwood may be better known, he was born into a long established line of master potters, unlike Spode who rose from financial penury to gain proprietorship of a huge pottery.

Josiah Spode (the first) learned his trade apprenticed to the well-known potter Thomas Whieldon, the most accomplished of Staffordshire’s mid-18thcentury manufacturers. Whieldon’s endless curiosity and willingness to experiment had a profound impression on the young Spode, and from there he worked in several partnerships until he took a position as the head of the Works of Turner & Bank in the 1760s.

Evolving from the coarse brown tavern wares of the early 1700s, by 1750 he had developed a fine white salt-glazed stoneware, with north Staffordshire potters producing a wide range of sophisticated tea, coffee, dinner, and dessert wares. In 1776, he was able to purchase property in the Church Street area of Stoke and take the title to the entire Works of Turner & Bank, which became known as the Spode works and would remain so until 2008.

Pioneering techniques at Spode

Spode was responsible for perfecting two extremely important techniques that were crucial to the worldwide success of the English pottery industry. Firstly, he perfected the technique for transfer printing in underglaze blue on fine earthenware.

This followed a piece of intuitive business in London where, in 1778, his son, Josiah Spode II, opened a warehouse at 29 Fore Street, Cripplegate, where he soon found that there was a growing demand for replacement pieces for Chinese porcelain services.

Always a man with an eye for the market, Spode senior began to experiment with underglaze printing on earthenware in order to produce these wares inexpensively and effectively.

Rivals Royal Worcester and Caughley had started transfer printing both underglaze and overglaze on porcelain in the 1750s, and from 1756 onwards, overglaze printing was also used on earthenware and stoneware. Until Spode applied his ideas, under- glazed, hot-press, printing was limited to the shades that could resist the temperature of the glaze firing, and a brilliant blue colour was the preferred option.

To upgrade this process from small tea wares to larger dinnerware required the invention of a more flexible transmit paper to move the designs from the copper plate to the body of the earthenware. This brought about the development of a glaze recipe that produced a perfect black-blue cobalt print.

Spode willow pattern

Spode employed two of the most skilled pottery artists of their day in engraver Thomas Lucas and printer James Richard. They had both worked for the Caughley factory during the early experiments in glazes.

Joined by Thomas Minton, also Caughley trained, Spode was able to introduce the signature blue-printed earthenware to the market. This was a ground-breaking achievement that redefined the British pottery industry. He perfected the process in 1784.

Spode’s early patterns were all copied or adapted from Chinese originals. His most famous pattern was produced around 1790 when he took the popular Chinese design Mandarin and added a bridge with three people and a fence from another Chinese design.

This became the famous willow pattern, the most popular underglaze blue pattern of all time.

Spode’s Blue Italian range

The next major step was the launch in 1816 of Spode’s Blue Italian range, with its floral chinoiserie border and rural Italian scene in shades and textures of cobalt blue, which has remained in production ever since.

In the early 1800s, many of the Blue Italian pattern pieces were found almost exclusively in wealthy households, from huge meat dishes, plates of all sizes and enormous soup tureens to cruet sets and foot baths. By 1827, Spode had become one of the world’s leading pottery manufacturers and Blue Italian was being exported around the globe. In the 1930s, one Spode catalogue recorded over 700 different shapes of Blue Italian available.

Italian origins

Engravers in the 18th century derived inspiration from scenes that had appeared previously as prints.

Researchers have attempted to unravel the mystery of the source of the Blue Italian scene. Although there is no one place that matches the scene in the pattern, a ruin to the left may be based on the Great Bath at Tivoli, near Rome. A row of houses along the left bank of the river is similar to those of the Latium area near Umbria, north of Rome, and a castle is similar to those found in Piedmont and Lombardy. Perhaps a travelling artist from Northern Europe could have made the sketches.

In 1989, the Spode Museum purchased a late 17th-century pen and wash drawing by an unknown artist. The scene is very close to that of the Blue Italian pattern and may well have been the original inspiration for the infamous Spode design.

Spode bone china

Spode’s second contribution to the history of porcelain was the development, around 1790, of the formula for fine bone china that was generally adopted by the industry.

His son, Josiah Spode II, was certainly responsible for the successful marketing of English bone china. By using 50 per cent bone ash, 25 per cent Cornish stone and 25 per cent Cornish china clay, Spode was able to create a ceramic which was very easy to fire in the same furnaces used to produce earthenware.

Bone porcelains, particularly those of Spode and contemporaries Minton and Coalport, established the definitive standard of soft-porcelain, the techniques which were used widely for years to come. In 1821, Josiah Spode II added another product to the Spode line: Felspar porcelain. Spode used felspar in the body of his bone china as a purer replacement for Cornish or china stone. It helped the raw materials of the porcelain recipe fuse at a lower temperature without distorting the body. The result was a white, very glassy ‘china’ which soon became all the rage.

William Copeland at Spode

The story of Spode from here until the present follows a pattern similar to so many other manufactories – success, failure, buy-outs, take-overs and mergers.

After Josiah Spode I died in 1797 his son Josiah Spode II went into partnership with London banker and tea merchant, William Copeland. During the ‘golden age’ of English ceramics in the 19th century, the company expanded to become the largest pottery in Stoke and an expert manufacturer of pottery.

William Copeland died in 1826, followed by Josiah II two years later. The company passed through the hands of several managers, including one of Spode’s sons, until 1833, when William Taylor Copeland – William Copeland’s son – acquired the business with Thomas Garrett. From then until 1847, the company traded under the name of ‘Copeland and Garrett’. In 1846, William Taylor Copeland took complete control of the business, and it stayed within the Copeland family for four generations until 1966.

Under the leadership of the Copelands, the company competed with Minton in making many of the most beautiful ceramic creations of the time.

Top artists such as C.F. Hurten were hired from Europe and the best pieces were displayed during the Great Exhibition of London in 1851 and two further international exhibitions in London and Paris, during 1862 and 1878 respectively.

Erik Olsen

After WWI, dinner and tea sets were sought after among young homeowners, prompting the large scale production of a number of transfer prints – often variations of patterns first seen during Josiah II’s time.

Well-known designs included Chinese Rose, India Tree, Italian and Christmas Tree.

The company also produced art deco and modernist styles in the 1930s by recruiting sculpture Erik Olsen who was able to capture the taste of the time along with new patterns and modern techniques.

Spode continued to produce bone china by maintaining the specialised skills of its employees and investing in new manufacturing processes. The company passed out of the Copeland family hands in 1966, after more than 120 years of sole ownership.

From 1966, the company changed hands numerous times before merging with Royal Worcester. The latter part of the 20th century saw signifi can’t advancements in ceramic decoration. Traditional skills and techniques were suddenly obsolete. The highly specialised engraving technique was no longer cost efficient and could be easily replicated by computers, which produced digital designs of comparable quality to their hand-crafted counterparts.

The current market for Spode

While Spode’s blue-printed wares are an important part of our cultural,and manufacturing heritage, they are also very affordable. Made for the masses, many pieces from the Victorian era are ubiquitous.

But that shouldn’t lessen their charm. It means you can buy a 160-year-old blue printed platter for £30. Some patterns are particularly desirable on account of their rarity or because their subject matter has wider appeal.

Pieces with identifiable landmarks, sporting scenes or prize livestock command a premium above those with more generic romantic landscapes or ‘sheet’ designs.

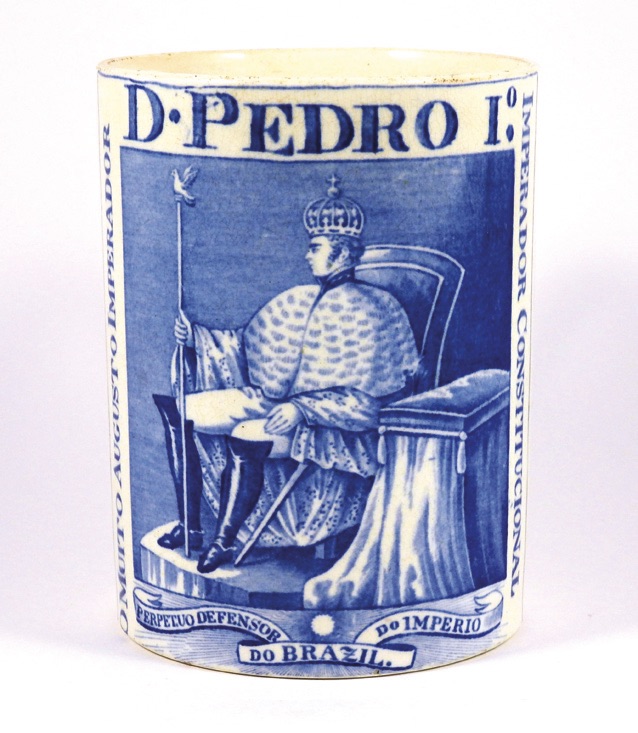

Much admired for its range of exotic and dramatic scenes, the ‘Indian Sporting’ series is traditionally cited as the king of all Spode patterns, but four-figure sums can also be commanded by pieces by lesser factories that depict subjects as diverse as polar exploration, cricket matches or the famous Durham Ox. The overseas market was key to British potters and a range of wares were made specifically for export, including those printed with patriotic scenes of North American landmarks and historic events.

These wares (in the heavy deep blue print favoured in the US) are sought after by Americana fans and command a premium higher than blue and white made for the ‘home’ market.

Types of ceramics

Earthenware

Earthenware is clay fired at relatively low temperatures of between 1,000 to 1,150°C. This results in a hardened but brittle material which is slightly porous (small holes through which liquid or air can go through), therefore it cannot be used to contain water.

To remedy this, a glaze is used to cover the object before it is fired in the kiln for a second time and rendered waterproof. Colour can usually denote the origin of the clay. Torquay ware uses rusty orange and iron rich Devon clays. Creamware uses good quality white Devon clay which can be fired at higher temperatures.

Stoneware

Stoneware is made from a particular clay which is fired at a higher temperature of 1,200°C. This results in a more durable material, with a denser, stone-like quality. The finished product will be waterproof and, unlike earthenware, does not need to be glazed. Black basalt and jasperware are forms of fine stoneware first produced by Wedgwood in the mid-18th century.

Porcelain

Porcelain comes from a refined clay fired at 1,200-1,450°C. The result is an extremely hard, shiny material often white and translucent in appearance.

Porcelain originated in China around 1600BC, hence the term ‘fine china’, or bone china – which included ground animal bone in the clay creating an even more durable material. Western porcelain is either hard paste (fired at more than 1,350°C), soft paste or bone china.

Traditional English bone china was made from two parts of bone-ash, one part of china clay kaolin and one part of Cornish china stone (a feldspathic rock), later replaced by felspars.

Find out more at The Spode Society

Trying to find a price for a 3 handled blue and white Copeland spode lg mud we brought from England over 52 yrs ago