Satsuma ware – a guide to collecting

Collecting Satsuma ware

Now is a great time to start collecting Japanese export Satsuma ware, with genuine Meiji-Period (1868-1912) pieces available for less than one hundred pounds, writes Kevin Page

Because of its long history and popularity through time, the price of Satsuma ware can range from less than one hundred pounds to many thousands of pounds.

This makes it a very accessible art form to many collectors including those that are just starting out.

Generally, late or post-Meiji pieces (1912 onwards) will be cheaper. When starting out and learning, it is best to familiarise yourself with the prices Satsuma ware is making at auction. In doing this, you should see a correlation between quality and price and it will help you to get your “eye in.”

The best way to start collecting is to look for pieces that you are drawn to. Fine quality objects will likely become very profitable investments for future years.

Do not just go looking for the wellknown artists. Step back and marvel at how a human hand could have painted these artworks. Look for pieces that appeal to you personally and then assess the detail, design, colours and condition. If you accidentally end up buying a late piece of little value, at least you have something you find aesthetically pleasing.

Island Life

Satsuma ware is a type of earthenware pottery originating from the Satsuma province in southern Kyushu, Japan’s third largest island.

The first kilns were established in the 16th century by Korean potters, kidnapped by the Japanese for their extraordinary skills. Prior to this, there was no real ceramic industry to speak of in the Satsuma region.

There are two distinct types of Satsuma ware. The original Ko-Satsuma is characterised by a heavy dark glaze, often plain, but occasionally with an inscribed or relief pattern. This style is rarely seen outside museums and it proliferated up until about 1800.

From around 1800, a new style – Kyo-satsuma – became popular. Famed for its delicate, ivory coloured ground with finely crackled transparent glaze, it was markedly different to Ko-Satsuma. These early designs focused on over-glaze decoration of simple, light, floral patterns with painted gilding. Colours often used were iron red, purple, blue, turquoise, black and yellow.

Eastern Promise

The first presentation of Japanese arts to the West was in 1867 and Satsuma ware was one of the star attractions. This helped to establish the aesthetic we are most familiar with today. This export style reflects the international tastes of the time.

Popular designs featured mille-fleur (a thousand flowers), and complex patterns. Many pieces featured panels depicting typical Japanese scenes to appeal to the West, such as pagodas, cherry blossom, birds and flowers and beautiful ladies and noblemen in traditional dress.

The height of popularity for Satsuma ware was the early Meiji period, from around 1885. The market became saturated with cheaper, mass-produced work lacking the quality of the earlier pieces.

By the 1890s, Satsuma ware had lost favour with the critics, but remained popular with the general public. It became synonymous with Japanese ceramics and was still being produced by some factories as late as the 1980s.

Care of Satsuma ware

Export Satsuma ware is sometimes referred to as “Cabinet Satsuma”, and, as such, is not intended to be used for practical purposes.

Highly decorative, it should be treated very much as a piece of art to be admired.

Because Satsuma decoration is painted on glaze, there is no protective layer like there would be on porcelain.

If you find your Satsuma is dirty you can dust using a soft cloth. Polish shouldn’t be necessary. If there is surface dirt, you can use a little water on a cloth to gently remove.

Dealers take note! Never attach stickers to the surface as you risk lifting the decoration or glaze. To remove a sticker, take a damp cloth or sponge and hold it until it becomes wet and you can gently remove it.

You may have to very gently scrape away sticky residue with your fingernail, but do take care. If you have high value satsuma or are in any doubt about how to clean or remove something we recommend you contact a restorer for professional advice.

Satsuma Restoration

As with any porcelain or pottery, restoration inevitably means a drop in value. If the piece is damaged, it can be very expensive to repair. In fact, there are not many restorers with the skill and experience to carry out such work sympathetically.

If you are collecting for enjoyment, however, a bit of damage or a repair can mean you could get a great price for a wonderful piece by a revered artist.

There are always exceptions to the rule, so these tips are intended solely as a general guide for reference purposes.

What to look for:

Earthenware pottery

All Satsuma ware is earthenware. You can tell it from porcelain by the weight. Pottery is heavier and won’t have the eggshell glow when held up to the light and won’t resonate like porcelain does when tapped. If the decoration looks like Satsuma but it is porcelain, then it is likely Kutani. (Kutani uses a lot of red and gold, this can be also be a giveaway.)

Glazed effect

You should be able to make out a difference between the background (usually cream in colour). It will have a shine and usually a delicate, crackled effect. You will be able to see the foreground painting is applied on top of the glaze creating a softer, more matt finish. You can sometimes feel it if you gently run your fingers across the decoration.

Satsuma Marks

Started becoming common from around 1870, so very early pieces may actually be unmarked. If the mark is in English, particularly if it reads “Made in Japan”, it means it will be, unfortunately, a very late piece.

You may often see a circle mark with a cross on the underside of a piece or sometimes incorporated as part of the design. This is the Shimazu Mon, which is the crest of the family that ruled Satsuma.

Style

Look for fine, detailed, miniature painting in a range of colours. The very finest examples will almost look like watercolour with layers of different colours blended together.

Faces should be fine, and birds and flowers more realistic than stylised. Fine painting and restraint is a hallmark of some of the best artists who would resist covering the whole piece in pattern, instead using negative space to enhance their design.

Earlier pieces tend to have a two-dimensional look to the landscapes. This is because they were inspired by the popular Japanese prints of the day.

If you notice foreshortening in a landscape image, it may mean it is a later piece likely influenced by Western design.

Imperial ware

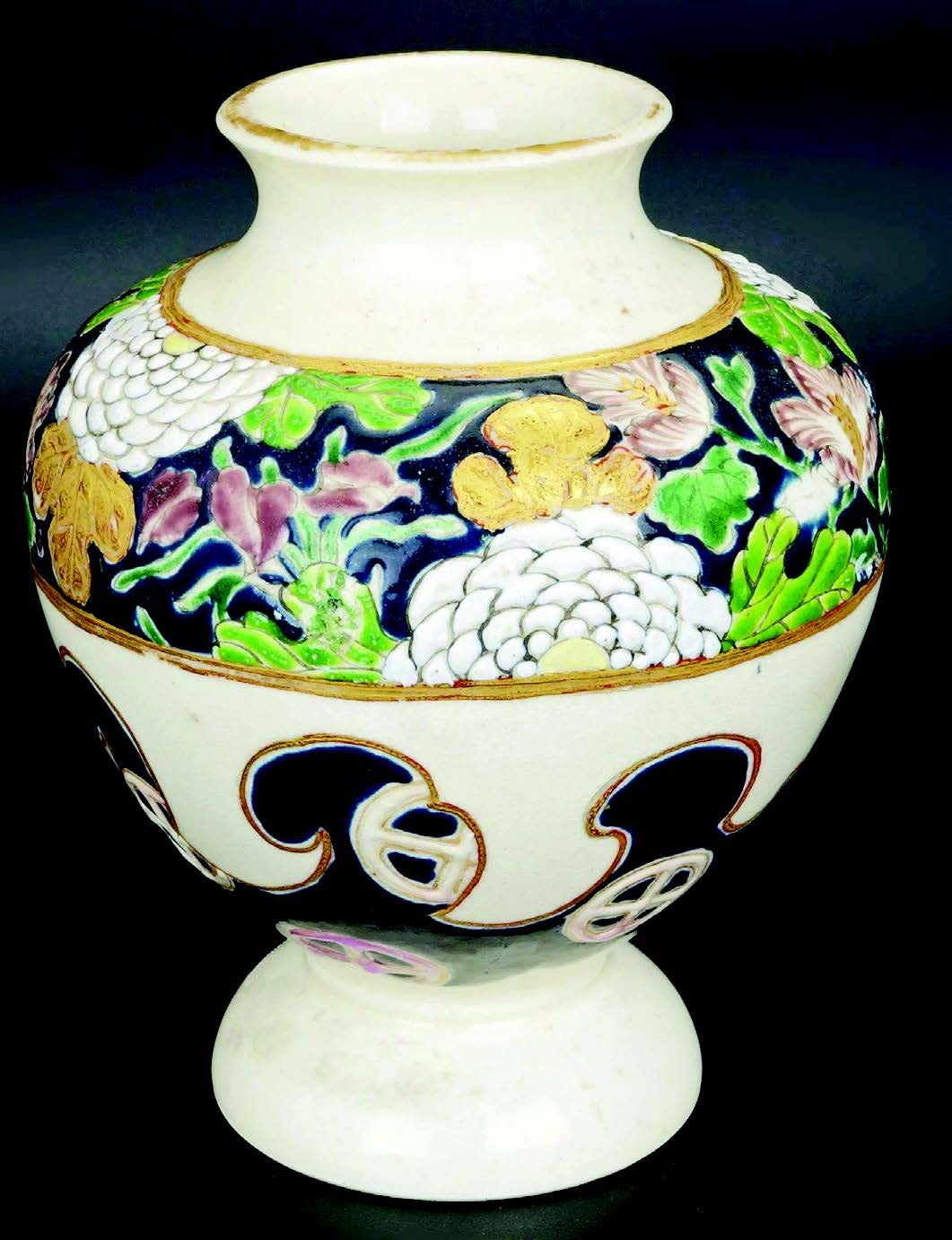

Another style of Satsuma ware decoration is what is known in the West as Imperial ware. It is usually late 19th century and has a distinctive thick glaze that often appears as though it has been iced with a piping bag.

The designs tend to be large, bold floral or geometric in bright reds, blues, yellows, blacks and purples. They also incorporate the famous gosu blue glaze, which can be dark blue, green or even black depending on the heat of the firing.

This style of decoration was hugely popular in the 1980s in Japan. In fact is was so desirable Japanese collectors would queue round the block just to view certain collections.

Presently it is not in favour, which means you may be able to find some good value pieces. Prices for this Imperial ware tend to be 10-20 per cent what they were in the 1980s so there is definitely potential to make a very good investment. Note, the term, “Imperial ware” is purely a Western phrase and not used in Japan.

Islington-based Kevin Page Oriental Art specialises in Meiji-period (late 19th century) art and ceramics, including fine Satsuma ware, bronzes and Okimono, multi-metal ware, Imari ware, embroideries and furniture. To discover more go to www.kevinpage.co.uk