Venini Glass – The Ultimate Guide

The celebrated Murano glassmaker Venini turned 100 this year. Expert and antiques dealer Holly Johnson considers the artists whose work was at the heart of Italian glass

Glassmaking has been at centre of the Venetian island of Murano for centuries, with its unparalled quality of craftsmanship making it sought after across Europe and beyond. But, despite the island makers’ supremacy, by the end of the 19th century, in terms of creativity, they were looking like a spent force. While Murano’s makers still looked to the past for inspiration, the rest of Europe was bowing to the influence of art nouveau. But change was afoot and, in 1921, with the vision of one man, glassmaking was about to undertake a sea change thanks to one of the greatest names in modern Italian glass – Paolo Venini (1895-1959).

Heart of Venini Glass

Venini was born in Cusano, Italy, on January 12, 1895, to a middle-class Lombard family. As a young man he studied law in Milan. During WWI he was stationed near Venice where he became fascinated with the glass mosaics and stained glass of St Mark’s cathedral.

After the war, Venini began a law practice but soon came under the influence of Venetian art and antiquities dealer Giacomo Cappellin (1887-1968) who convinced the young lawyer to join him as a business partner.

Together in 1921 they formed a new Murano glass enterprise with dreams of producing something very different from what had been produced previously.

It was an ambitious project which the Venetian artist Vittorio Zecchin (1878-1947) immediately decided to join, in the role of artistic director.

Forging Forward

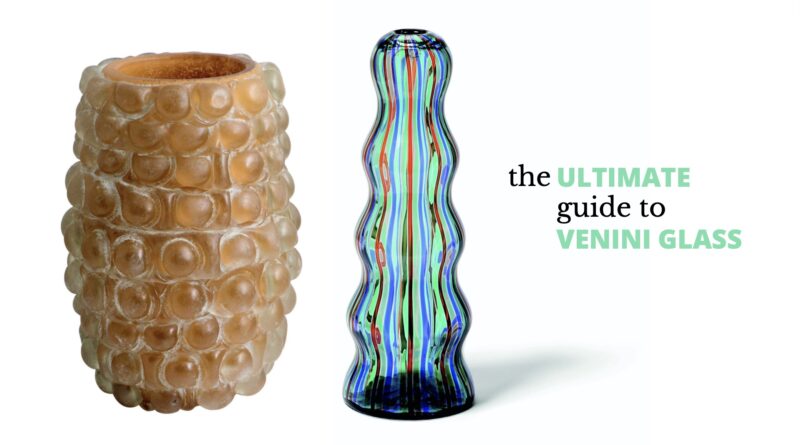

The company was built along traditional lines but sought to embracing the avant garde. In the same year, Zecchin created the famous vase Veronese, which was to become the symbol of the company.

In 1925, following a dispute with Zecchin, Cappellin and Venini split their business in two. Venini’s business took the name Vetri Soffiati Muranesi Venini & C., along with a new, visionary art director, Napoleone Martinuzzi (1892-1977).

Venini soon became synonymous with bold, coloured art glass and lighting at the cutting edge of contemporary aesthetics. Within years he was the most important glassworker on the island of Murano.

From 1927 to 1932, he explored a series of new, techniques, including pasta vitrea (opaque glass), vetro incamiciato (layered glass), and vetro pulegoso (bubble glass) kickstarting experimental forms. Venini’s reputation for innovation grew through exhibitions at national fairs, including the Venice Biennale, Monza, and eventually the Triennale di Milano.

Venini Glass Makers

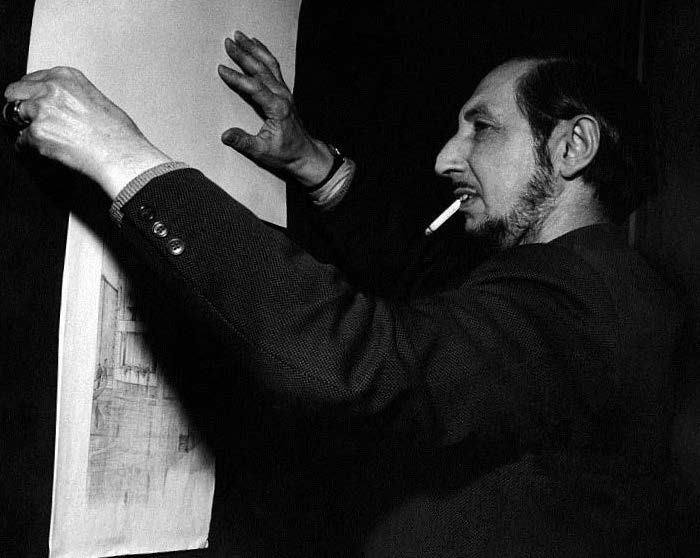

In 1932, Martinuzzi decided to dedicate himself to sculpture, and Venini’s artistic directorship went to architects Tomaso Buzzi (1900-1981) and Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978), then in his mid-twenties. As art director Scarpa soon began combining old techniques with new adventurous colours.

Born in Venice, Scarpa studied architecture at the Accademia di Belle Arti graduating in 1926. His exploration of the medium of glass began while he worked at MVM Cappellin glassworks between 1926 and 1931.

However, it was Scarpa’s next post at Venini where he redefined the parameters of glassblowing in terms of aesthetics and technical innovation.

Scarpa was considered the “Frank Lloyd Wright of glass” as, like the Amercian architect – and later Gio Ponti – they were all architects who shared an enduring love of glass.

Like Father Like Son

For the next 15 years Carlo Scarpa worked closely with Venini master glassblowers creating a number of innovative new styles. One of the first he pioneered was bollicine, named after the tiny bubbles of air suspended in the glass.

Two years later, he developed the mezza filigrana style, creating very thin glassware decorated by internal swirling lines. His and Venini’s collaboration was put on display at important international showcases such as the Milan Triennale and Venice Biennale in Italy during the 1930s and 1940s.

After Scarpa left Venini in the 1940s to devote himself to architecture, his son, Tobia (b. 1935), joined the firm and went on to create his most well-known Occhi vases, resembling nets of single colours enclosing clear glass windows or ‘eyes’.

Fulvio Bianconi (1915-1996)

When Fulvio Bianconi met Venini in the spring of 1946, he was already a well-known graphic designer, illustrator and caricaturist.

Born in Padua in 1915, Bianconi moved with his family to Venice at the age of seven where his natural talent for drawing allowed him to study at the Carmini School of Art, and later at the Accademia di Belle Arti. A year later, in 1947, Bianconi brought the humour and originality of his illustrations to his glasswork, producing, among other designs, Pezzati, (patchworks) – made up of bold, horizontal stripes woven together out of strips of coloured glass. He later introduced a Scozzese series, Italian for Scottish, which was based on tartan.

Bianconi was also responsible for the famous Venini Fazzoletto (handkerchief) vase, which became the symbol of the company in the post-war years. The design aimed to capture the flow of a tossed handkerchief suspended in mid air. A square of patterned glass was heated and draped over a post and allowed to fold naturally and cool in the shape of a bowl or vase that looked just like a coloured silk handkerchief.

Many pieces from these series would be included in the Italy at Work exhibition, which travelled the United States for three years (1951-1953) and exposed millions of Americans to Italian design. By the time the show ended, the name Venini was synonymous with Murano glass, and Bianconi was heralded as a new force in creative glass design worldwide.

Gio Ponti (1891-1979)

After Paolo Venini’s death in 1959, his son-in-law, Ludovico Diaz de Santillana, took the company in a new direction. Responding to the tone of the times, Santillana began to invite artists from around the world to create a forward-looking design ethos.

During the 1930s, Gio Ponti conceived some of the most emblematic buildings in Milan that reflect the new architectural trends of the period, but his spell at Venini brought out the painter in him.

As a glassmaker his designs ranged from bottles wrapped in frilly spirals – suggesting the hemline of a skirt – to conservative pieces with a colourful twist, such as a bulbous-bottomed bottle whose colour graduates from red to green.

Italian Polymath

Another 20th-century Italian polymath who made a name for himself at Venini was the architect, designer and poet, Alessandro Mendini (1931-2019).

His postmodern approach was characterised by combining elements from various cultures and eras and mixing them with a certain level of kitsch.

He said: “At Venini I did some very interesting things, many of which used their signature techniques and colours. Over the years, little by little I designed vases, lamps, light sculptures, very large vessels, figures, horses and totems.”

In 2002, he created a large red face wearing golden earrings by Cartier inspired by the sculptures of Easter Island. In the 1980s, along with Ettore Sottsass and Andrea Branzi, he became known as one of the important designers behind “nuovo design” or “neomodernism”.

Cheshire-based interior designer and antiques dealer, Holly Johnson, has a range of Murano glass including pieces by Venini-trained Pino and Silvano Signoretto, for more details go to www.hollyjohnson.co.uk

Island life

Centuries before Venini set up in Murano, glass making was in full swing on the famous Venetian island. While glassmaking had flourished in the city from the earliest times, it was in 1291 when craftsmen were instructed to relocate to Murano to avoid the risk of fire.

After Islamic glassmaking started to decline – especially when Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453 – Eastern glassworkers flocked to Venice introducing new processes of enamelling and gilding.

Some of the decorations revived motifs from the Renaissance iconography such as Angelo Barovier’s (d. 1480) famous blue drinking cup.

But from the beginning of the 18th century Murano makers faced fierce competition from Bohemian glass, produced in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The fall of the Republic of Venice, in 1797, added to their woes.

One strategy was to revive ancient techniques, adapting them to the fashion of the times – a tradition maintained by the makers at Venini who went on to reinvent them while maintaining traditional skills.

Collecting Venini glass

Art dealer Dan Ripley reveals what the would-be collector needs to know about collecting Venini glass

Beware of ‘Venini’ glass that has been doctored to look old. Glass can be scratched, buffed, ground and dirtied to appear aged.

Deep scratches or cracks can reduce the value substantially (unlike furniture). Glass colours do not fade, however, so a keen eye for colour can sometimes be illuminating. Notice that Venini’s new pezzati have darker green patches than the originals.

Phony labels can also be affixed and inscribed signatures and dates

The double-edged sword of the incredible number of books compiled in the last decade to document the work of Fulvio Bianconi, Carlo Scarpa and others has been to provide all the data needed to create the best fakes and forgeries of their work.

Be aware that Venini glass from the 1950s is typically identified by a three-line acid stamp ‘venini murano ITALIA’.

However, take for example the ubiquitous Handerchief (fazzoletto) vase, which is almost always acid stamped. The problem is, in some cases, the design only allows a small area for the stamp, so not all vases have the complete signature.

On the smaller vases the stamp would not fit into the pontil area, so it is only by tilting the vase towards the light that it becomes evident. But since only Venini used the acid-stamped signature, just seeing part of it is enough to authenticate the vase as Venini. Also, genuine handkerchief vases have a highly-polished pontil (the mark left when the ‘punte rod’ was broken off a work of blown glass) – if it is not polished then it’s not Venini.

Be aware of Chinese fakes which are incredibly heavy and lack the clarity and finesse of the real thing.

Dan Ripley is a third generation Indianapolis art dealer who regularly holds glass sales at www.antiquehelper.com

Record price for Venini

In 1960, after winning a Fulbright Travel Grant, the young American artist Thomas Stearns (1936-2006) left Cranbrook Academy to start a two-year tenure at Venini. However his ambitious plans for elaborate asymmetrical forms was not matched by his knowledge of Italian of which he was completely ignorant.

His controversial designs also drew criticism from Venini’s master blower, Arturo Biasutto, and when Stearns won an award at the 1962 Venice Bienniale, it was rescinded when judges discovered Stearns was an American.

Because his designs were too difficult to put into mass production, they became limited-edition art objects, much sought after by collectors.

His 1962 sculpture La Sentinella di Venezia (The Sentinel of Venice) set a world record when it sold for $737,000 at Wrights auction house in Chicago in 2018.

A Stearns’ piece also held the previous auction record for Venini glass when two pieces realised $612,000 at Sotheby’s in 2016.