Alfred Wallis – the ultimate guide

Home to the largest collection of works by outsider maritime artist Alfred Wallis, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge reveals how he changed the direction of British modern art

What is a generally accepted wisdom is that artists tend to produce their most creatively expressive, adventurous and ground-breaking works during their younger years.

However, despite the Cornish painter and mariner Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) picking up his brush late in life – at the age of 70 – he still helped to shape the face of 20th-century British modernist art, and remains much in demand some eight decades on.

While little is known of his early years, Wallis was born in Devonport, Plymouth on August 8, 1855, and records show that by 1876 he was working as a sailor and married to a widow named Susan Ward, 23 years his senior. With the marriage came the responsibility of a new family, including his wife’s five surviving children.

Varying accounts find Wallis working onboard deep-sea boats in the Atlantic, then as a crew on local fishing boats, before finally moving to St Ives in Cornwall.Here, he eked out a living in a variety of employment and enterprises, including periods as a labourer, constructing government huts during WWI, selling ice cream and even starting his own marine scrap business.

Even after Susan’s children had left home, the couple’s precarious financial situation did not improve. When she died on June 7, 1922, an increasingly isolated and impoverished Alfred was left to grieve alone.

Paint Relief

It was around this time that Wallis made the unlikely decision to start painting, something of which he had hitherto shown no interest or inclination to do. While the catalyst for this new creative chapter remains obscure, most theories suggest it was an activity to stave off his loneliness and ongoing grief.

In his book, Alfred Wallis: Primitive, the artist and writer Sven Berlin suggests the grief-stricken artist theory may be true. According to one local shopkeeper, Wallis said: “Aw! I dono how to pass away time. I think I’ll do a bit a paintin’ – think I’ll draw a bit.”

Wallis soon enthusiastically embraced his new calling creating a prolific body of work. Despite, or perhaps because of, his lack of formal artistic training, the paintings and sketchbooks give full flight to his sense of nostalgia, vividly bringing to life the memories of his time at sea, alongside the boats and ships that sailed along the Cornish coastline.

From twin-masted and multi-sailed brigantines to modern steamers or the flying scuds used by in-shore fishermen, the vessels are all depicted with the same captivatingly naive honesty.

Holiday Spot

In a moment of cultural serendipity, in August 1928 the avant garde artists Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, both pioneers of abstract art and modernism, were holidaying in St Ives when they spotted Wallis’ paintings through the doorway of his cottage at 3 Back Road West.

Keen to discover more, the pair ventured within and were amazed to find countless paintings roughly nailed to the walls of Wallis’ home. They soon purchased a large number to take back with them to London where they shared them with like-minded, abstract-leaning artists and critics. This chance meeting was to propel Wallis and his work to an acclaim that the septuagenarian would find hard to imagine or fathom.

Just a year after their first meeting, Nicholson arranged for Wallis’ artworks to be included in an avantgarde group exhibition organised by the art group, the Seven and Five Society in London. Nicholson had joined the society in 1924, helping to transform its creatively conservative outlook with the aid of other modernists such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore.

With such influential young artists championing his work, along with the prominent critic Adrian Stokes, Wallis was soon receiving high praise from the modernist milieu of the day for his unique techniques and unusual choice of materials.

Natural Talent

Throughout his short career, Wallis refused to use professional artistic paints or pigments, instead employing the weatherproof paint used on boats for his pictures painted on an assortment of found ‘canvases’, ranging from recycled cardboard, to old fish boxes and driftwood.

How he used the paint could also change to capture different elements of his scenes, from rolling seas to heavy storm clouds. Elsewhere, other pictures demonstrate straighter and concise line-drawings that capture his subjects in a manner more akin to the technical drawings of a drafting technician.

Wallis’ desire to create paintings that were immersive to the viewer can be seen in images of ships pitching and tossing on the waves. His landscapes featuring the local geography and landmarks of St Ives, including the harbour, lighthouse and rows of houses, also appear in semi-abstract or condensed form.

Some critics have claimed the fluidity and ‘untutored’ nature of his images – where relative dimensions are distorted, perspective skewed and angles slanted – is due to Wallis’ lack of artistic tuition. Others argue it is just this technique that allows him to capture the essential and innate ‘spirit’ of the Cornish environment, rather than merely representational scenes of his beloved countryside.

The Influence of Alfred Wallis

Wallis’ influence on the group of younger artists of the Seven and Five Society – all of whom were keen to redefine the boundaries of art – is obvious. Both Nicholson and Wood, who helped to establish St Ives as a bastion of British modern art, adopted Wallis’ use of unconventional materials on which to create works, such as unframed wooden boards.

Similarly, the muted and restrained colour palette that Wallis used for his coastal scenes is present in their own works from the era, as is his unique sense of perspective and proportion.

Nicholson wrote of the elderly artist’s approach, “I don’t think good Wallis is representational, it is simply REAL.” Christopher Wood concurred with his friend, stating how, “I’m more and more influenced by Alfred Wallis – not a bad master though; he and Picasso both mix their colours on box lids!”

However, despite such plaudits, Wallis did not benefit from his newfound fame during the latter years of his life. While St Ives became established as a centre for modern and abstract developments, Wallis never considered himself part of this artistic movement. With the onset of old age, his continued eccentricity and deteriorating mental health, he was eventually sent to live in the Madron Public Assistance Institution where he finally died in 1942.

Alfred Wallis and Kettle’s Yard

The collection of mystical seascapes by the Cornish painter Alfred Wallis at Kettle’s Yard in the centre of Cambridge is the largest of its kind anywhere in the world.

The gallery offers visitors the chance to explore the many Alfred Wallis paintings from the collection on permanent display at Kettle’s Yard.

The late Harold Stanley (‘Jim’) Ede, a former assistant curator at the Tate, and founder of Kettle’s Yard, was a huge supporter of Alfred Wallis, buying a large number of his work while he was alive and cementing his reputation after his death.

Though they never met, the two men were lively correspondents between 1929 and 1938, during which time Ede amassed more than 120 paintings. As a result, Kettle’s Yard has the most substantial institutional holding of work by Wallis anywhere in the world.

After Wallis’ death, Ede said of the artist in 1945: Wallis was an innocent painter, with a living rather than an intellectual experience, a power of direct perception […]. Each painting was to him a re-living, a re-presenting, achieved unconsciously in regard to the act of painting, but vividly conscious in its factual awareness.

To find out more about the various exhibitions held at Kettle’s Yard and the works on display by Alfred Wallis go to www.kettlesyard.co.uk

Alfred Wallis Q&A

Kettle’s Yard’s curatorial assistant Eliza Spindel shares her love of Alfred Wallis

Explain the appeal of Wallis’ art?

He appeals to a wide variety of people on many different levels. To art historians, Wallis represents an important figure in the development of British modernism. But aside from his historical significance, it’s easy to fall in love with Wallis’ vivid evocation of the sea and the Cornish landscape. I think many viewers also feel an emotional connection with Wallis: the fact that he only began painting in his seventies with no formal training, to fend off the loneliness he felt after the death of his wife.

Does his work divide opinion and, if so, how?

Yes, Wallis’ status as an untrained artist can be polarising. He has traditionally been seen as ‘naive’ – unaware of his talents and the artistic choices he was making. Many people now take issue with this view, believing Wallis to be more sophisticated and self-aware than he is given credit for.

Where does he sit in the canon of ‘outsider artists’?

As an untrained artist, Wallis was part of a growing interest in ‘outsider art’ during the early 20th century. Modern artists seeking new forms of expression found inspiration in these so-called ‘primitive’ and ‘naive’ artists.

What impact did the artistic milieu of St Ives have on Wallis?

It’s difficult to say how much they impacted him. Wallis was probably aware of the artists and galleries in St Ives, and perhaps they inspired him to take up painting, but he seems to have made a point of never engaging with them.

What influence did Wallis have on British modern art?

When artists Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood first encountered Wallis’ work in 1928, they were particularly drawn to his fresh and instinctive approach, which ignored many of the formal rules of painting that they had been trying to shake off. They introduced his work to other avant-garde artists in London, and Wallis became an important inspiration for many of them.

Was Wallis aware of his own artistic significance – how did he view it?

Wallis seems to have been aware of his artistic success, but remained relatively disinterested in it. There is a famous story of Ben Nicholson showing Wallis a postcard of his work at MoMA, and Wallis responding, unimpressed: ‘I’ve got one like that at home’.

How significant is it that he had no formal artistic training?

To his admirers, Wallis was special because he was ‘unspoilt’ by academic artistic training. Today, many people continue to be inspired by Wallis – the idea that it’s possible to make art without training or professional materials.

Did his work evolve or was he ‘fully formed’ as soon as he started painting?

It’s difficult to tell because Wallis never dated his works, so we can’t construct a secure chronology. He also kept returning to his favourite subjects over and over again. There are a few paintings that we know are later works, and some have suggested that these are more sophisticated and complex, implying that there was some technical development.

Would you describe him as a maritime artist?

Although Wallis’ work draws on his experiences as a mariner and fisherman, I wouldn’t describe him as a maritime artist in the traditional sense. Wallis painted from his memory or his imagination, so his works often capture feelings and atmospheres rather than real-life scenes. They feel universal and timeless. Wallis was very religious, so there are often spiritual elements too.

What is it about Wallis’ work that makes it so in demand today?

Almost a century later, it continues to feel fresh and exciting. His style is instantly recognisable and, although it may seem simple at first, there is so much depth and richness in each painting. Spending time with this exhibition has allowed me to discover the many layers to Wallis’ work – I hope our visitors have too.

What are your favourite pictures at Kettle’s Yard and why?

Ship with seven men, net and gull. To me, it’s Wallis at his best: conveying the movement and drama of hauling in the fishing nets, the rolling waves, the swirling rainclouds and seagulls circling above.

Value of Alfred Wallis paintings

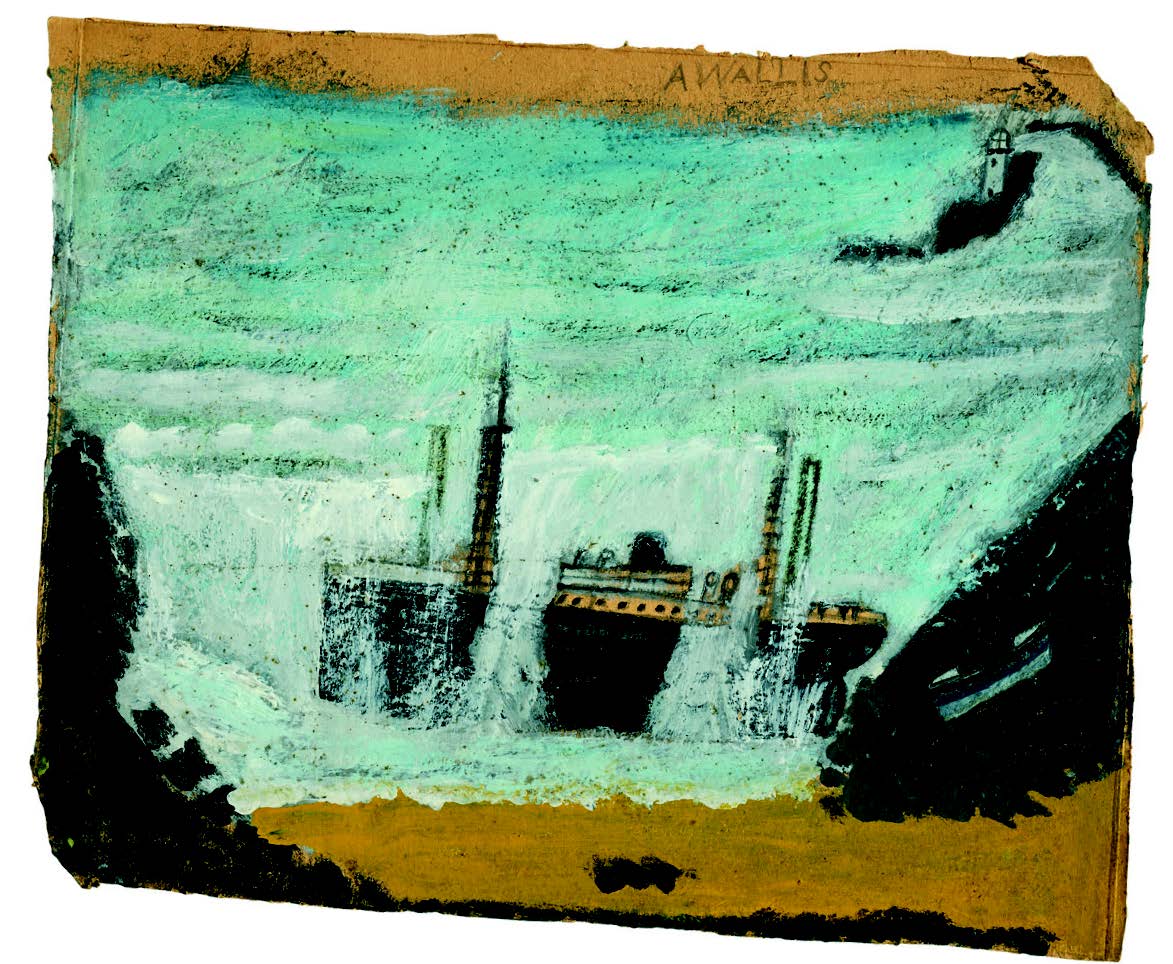

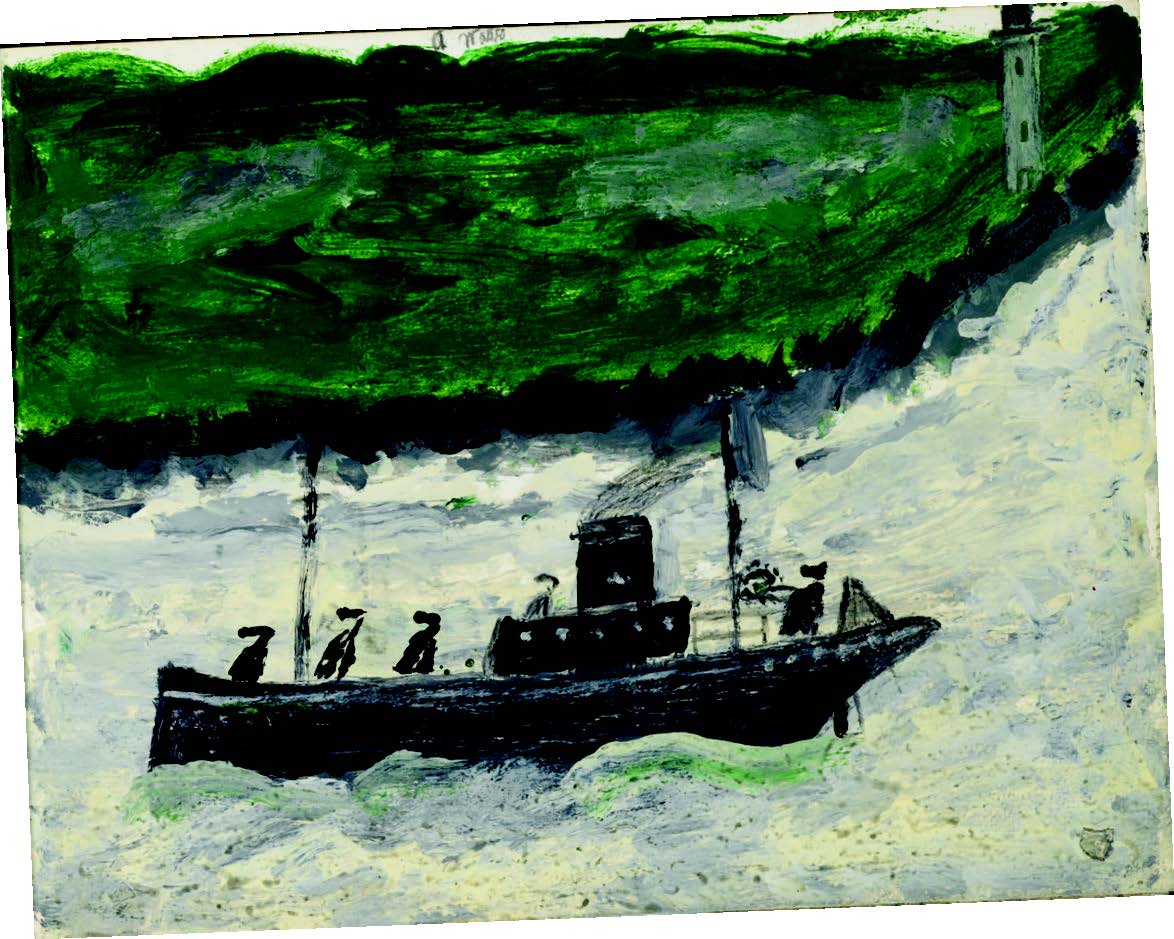

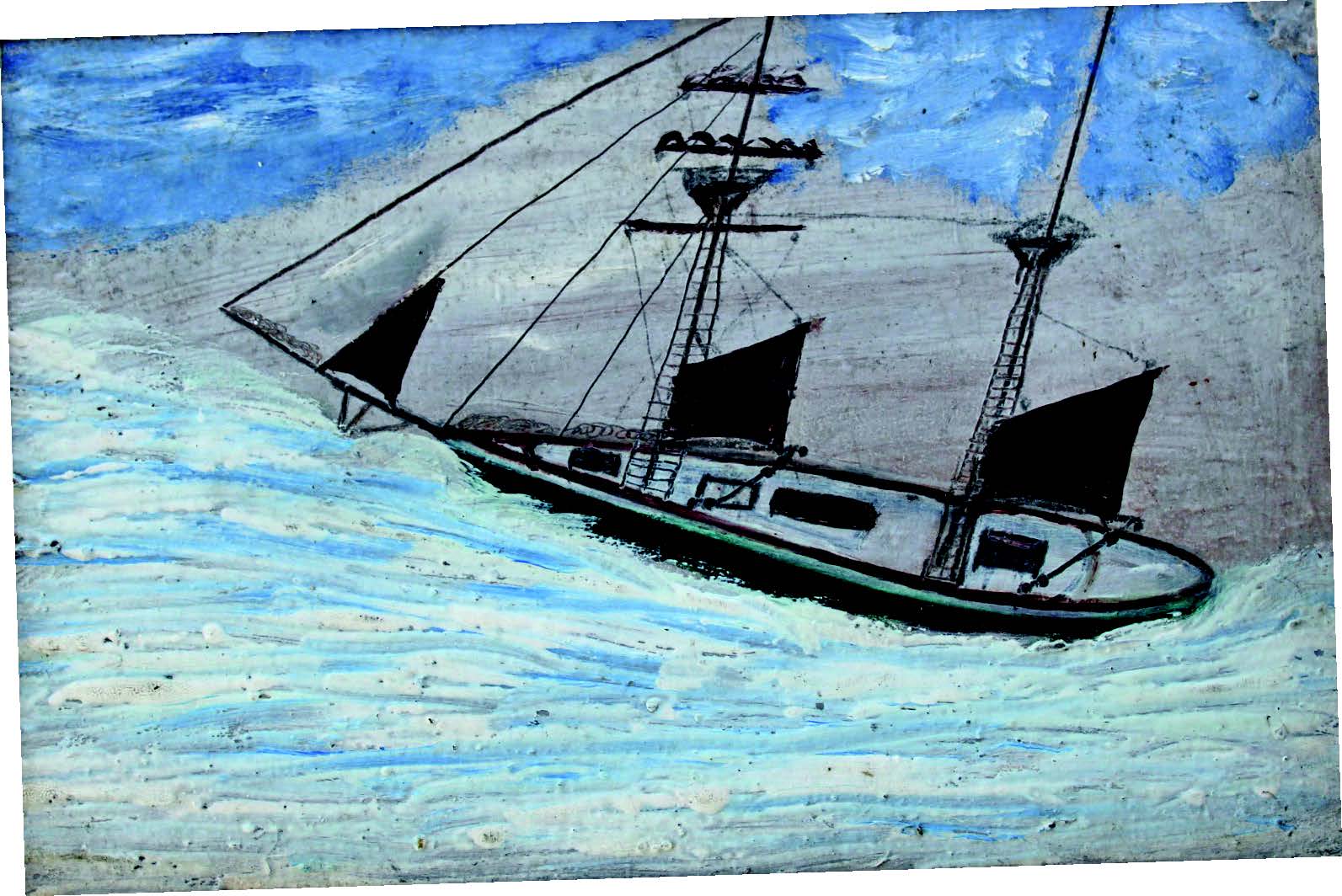

Works by Alfred Wallis always generate interest at auction, with collectors around the world drawn to his simple studies of boats and the Cornish coastline, such as these examples here.

Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) West Country Schooner on a Swell, oil on card, sold for £28,750 at Lawrences Auctioneers in Crewkerne, Somerset in October 2020. Image courtesy of Lawrences Fine Art Auctioneers Ltd

Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) Sailing Ship in Stormy Sea, oil and pencil on card, signed ‘Alfred Wallis’ on the lower right, sold for £24,000 in Christie’s Modern British Art Sale on March 2, 2021. Image courtesy of Christie’s

Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) A Steamship and a Schooner Passing the Coast (recto); A Path Through a Wood (verso), oil and pencil on an artist’s paintbox, signed ‘alfred wallis’ on the lower right recto, sold for £100,000 at Bonhams in 2020. Image courtesy of Bonhams