Backs to the front in Chiswick Auctions painting and fine art sale

Sponsored Post

Painting & Fine Art, Old Masters

Two forthcoming sales at Chiswick Auctions next week offer unique perspectives and insights into Fine Art – but perspectives and insights from the back rather from the front, as it were. The London auction house’s next Old Master Paintings & Fine Icons Sale and third Fine Frames Sale of the season are both being held on Tuesday 10 May.

Dr Albert Godetzky and Luke Price, Old Master and frames specialists respectively, explain how they examine the entirety of paintings.

The ‘front’, or painted surface of a painting, and of its frame, are what most people look at and react to. However, if we look at the backs of pictures and frames we often learn a great deal more than we do from only looking at the front. Stories and secrets are sometimes revealed – and this is very much the case with items in our two forthcoming sales.

Paintings – foundation and conservation

An easel painting may be created on a support of either canvas, paper, wooden panel, or even on metal (for example a copper plate) or other hard bases. Each type of support will have been chosen by the artist either to best suit the end effect they wished to create, or reflects the materials that were available at the time of the painting being made, or the then-current fashion in paintings. In our forthcoming Old Master Paintings & Fine Icons Sale we have examples of paintings both on canvas and on wood panels as well as metal supports.

As a painting ages, its base support (wood panel or canvas in particular) can deteriorate and affect the stability of the painted surface image that we wish to see. Wood panels can shrink and warp; canvas can age, sag or tear. The paint itself may become loose or detached from the wood or the canvas if this deterioration is pronounced. We want our art to last as long as possible – ars longa vita brevis – and so how is this deterioration addressed and mitigated? This is where the work of a paintings conservator comes into play.

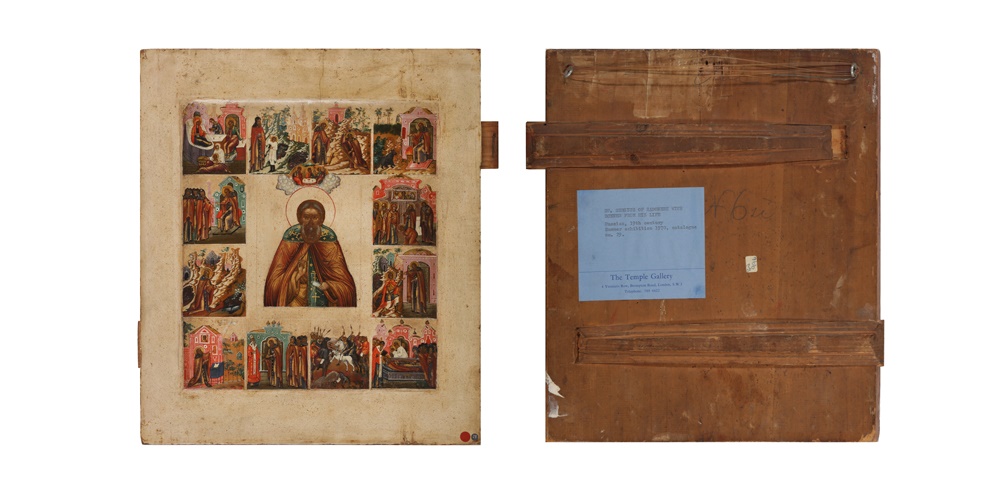

In our sale we have a number of Icon paintings of very high quality and we will look at three of these: two of the Russian school and one of the Greek Ionian school (Lots 40, 38 and 44). All three are on wooden boards, and as these boards have aged and warped over the years the painted surface has followed the wood. There have been conservation attempts to stabilise the panels and limit further curving of the panel. This has been achieved by using reinforcing battens at the rear, a relatively simple approach involving the insertion of one or two stabilising batons. A more dense and comprehensive conservation technique is the reinforcement of panel paintings, termed ‘cradling’, that can be seen on the rear of our Anthonie Verstraelen painting. This cradling, of more interwoven battens than with the icons, aims to help stablise the wood as it ages and also as it moves in reaction to the changes in heat and humidity in which the icon is kept and displayed.

There’s more at the back..

It is notable that our wonderful painting attributed to David Teniers and his workshop is on a very stable board, showing very little, if any, evidence of warping or deforming. What is even more fascinating to see is that the rear of this particular painting has a number of sealing wax impressions, showing coats of arms which make up the provenance of this particular painting – in this case possibly from the Habsburg territory of Bukovina (present day Romania) during the nineteenth century. We also have in our sale a painting attributed to Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder, of Abraham Kneeling for the Three Angels and again this is a panel painting with the addition of the number of important handwritten notes – ‘provenance’- on the back of the panel. Interestingly, this panel painting has also not required cradling on its back and again shows little, if any, evidence of warping or deforming.

Turning to paintings on canvas, the woven cloth base for a painting can sag or become loose on its stretchers over time, threatening the painted surface itself. The canvas can be re-tensioned by stretching its wooden supports back to their original shape, but reinforcing a canvas painting can also be a matter of remounting the entire original canvas on another more stable, firmly-stretchered canvas. This can be seen in our pastoral landscape painting by Thomas Barker (‘Barker of Bath’) whose Pastoral Landscape has had the original canvas re-mounted on another firmly-stretched canvas; this has helped stabilise the painting, maintain its flatness and conserve it in a stable and manner for the future.

Frames: around the back (and the front)

Let’s turn to a picture’s frame – and its great importance as partner to the painted work. In regard to panel paintings a frame may assist in stabilising the wooden foundation of a panel painting but it must not restrict the movement of the panel – a frame must allow for the small movements and fluctuations of the wood itself, as a too firmly-fitted frame would not allow the panel to react to its environment, and that itself can cause major problems. The third of our icons illustrated here (Greek in this case) – see above for photos – has been framed very respectfully, in that the mounting of the icon within the frame allows for movement as well as adding a very suitable framing to the work itself.

Rembrandt: framed as a fashion victim

In fact, in recent years institutions and private collections have seen a framing renaissance, with many existing pairings of pictures and their frames being readdressed. Many Old Master Paintings now being re-framed are those that were previously re-framed during the 18 and 19th centuries by royalty and wealthy connoisseurs in the then current taste of that century and country. For example, highly-valued Dutch masters like Rembrandt were often re-framed by French and British collectors in the 18th century taste – for example, in our Fine Frames Sale, lot 151 A French 18th century Louis XV fully carved and gilded frame is a style commonly associated with such collections. But, it is more likely that the type and design of frame that would have been the original setting for the picture would have been lot 136 in our sale: A Northern European 17th century-style polished wood ripple frame which greatly enhances Rembrandt’s treatment and technique and would allow the painting to be presented as originally intended, rather than overwhelming it with grand gilding.

Back to the back – and more revelations

On some occasions a frame will reveals its provenance and history by bearing old labels of previous marriages to past Old master Paintings – and in our sale we have the fascinating lot 111 An Italian 17th Century carved, gilded and painted Cassetta Frame which bears labels reading “Conte Alessandro Contini Bonacossi, Florence / Exhibited at Mostra di Leonardo da Vinci, Palazzo dell’arte, Milano 1939 “ and also “The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Painters of reality: the legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy, 2004”. Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi (1878-1955) donated his wonderful collection to the Italian state in 1969. As this frame shows, frames have often been re-purposed and re-sized to meet the changing paintings they house and collections they hung in. But their history may be visible to allow us to discover what masterpieces they have housed. The labels on the back of this frame would indicate that it housed a painting by Italian master Bernardino LUINI (c.1480/85-1532) of San Sebastiano, and our research has revealed that the painting is now in the collection of The Hermitage in St Petersburg, and the frame is in our sale.

So remember – always look behind the picture, and frame; particularly if you want to learn more of the picture’s story and history- or what its framing can tell you – perhaps you too will see what secrets there are to be discovered!

Old Master Paintings and Fine Icons Tues 10 May at 11am

VIEW THE CATALOGUE HERE

Fine Frames Tues 10 May at 2pm

VIEW THE CATALOGUE HERE